Alex Hammond

Alex Hammond’s Personal Narrative was derived from information found in public records, military personnel files, and local/state historical association materials. Please note that the Robb Centre never fully closes the book on our servicemembers; as new information becomes available, narratives will be updated to appropriately represent the life story of each veteran.

Please contact the Robb Centre for further clarification or questions regarding content or materials.

Military Honor(s):

Distinguished Service Cross

Citation: The President of the United States of America, authorized by Act of Congress, July 9, 1918, takes pleasure in presenting the Distinguished Service Cross to Private Alex Hammond (ASN: 2169003), United States Army, for extraordinary heroism in action while serving with Company E, 366th Infantry Regiment, 92d Division, A.E.F., near Lesseux, France, 4 September 1918. Although he was severely wounded, Private Hammond remained at his post and continued to fight a superior force which had attempted to enter our lines, thereby preventing the success of an enemy raid in force.

Croix de Guerre with Silver Gilt Star

Citation: French Croix de Guerre with Gilt Star, under Order NO. 17.470 “D”, dated May 17, 1919.

Life & Service

- Birth: 1 March 1895, Harvest, AL, United States

- Place of Residence: Harvest, AL, United States

- Race/Ethnicity: African American

- Death: 5 June 1931 Wetumpka, AL, United States

- Branch: Army

- Military Rank: Private First Class

- Company: [E]

- Infantry Regiment: 366th

- Division: 92nd

Alex Hammond was born to William (1855-?) and Molly (Davis) (?-?) on March 1, 1895 in Harvest, Madison County, Alabama, the youngest of nine children; Caroline (1882-?), Eva (1884-?), Emmet (1888-1956), Laura (1891-1948), Annie (?-?), Edith (?-?), Thomas (?-?) and Mandy (1892-?). In his youth, Alex worked as a farm hand on his parent’s property in Alabama.

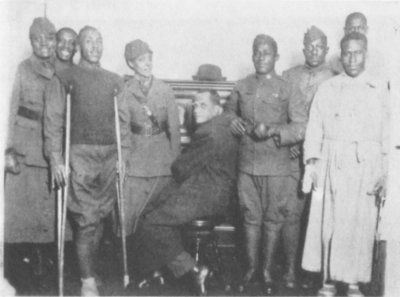

Alex enlisted in the U.S. Army on 29 October 1917 in Alabama as a Private, assigned to Camp Dodge, Iowa, later transferred to Camp McClellan, Alabama. Private Hammond and his company left Camp Upton, New York on the U.S. Army Transport Ship Vauban on 14 June 1918, arriving in Brest, France on 20 June. Private Hammond received the Distinguished Service Cross and Croix de Guerre with Gilt Star for his actions on 4 September 1918 near Lesseux, France;

“The President of the United States of America, authorized by Act of Congress, July 9, 1918, takes pleasure in presenting the Distinguished Service Cross to Private Alex Hammond (ASN: 2169003), United States Army, for extraordinary heroism in action while serving with Company E, 366th Infantry Regiment, 92d Division, A.E.F., near Lesseux, France, 4 September 1918. Although he was severely wounded, Private Hammond remained at his post and continued to fight a superior force which had attempted to enter our lines, thereby preventing the success of an enemy raid in force”. Awarded DSC by CG, AEF, November 8, 1918. Published in G.O. No. 139, W.D., 1918. French Croix de Guerre with Gilt Star, under Order NO. 17.470 “D”, dated May 17, 1919.

Private Hammond received gunshot and hand grenade-shrapnel wounds to the right leg, right wrist, and left thigh in the Alsace-Lorraine region on 4 August 1918. Private Hammond was sent for surgery at a hospital in Dijon, France, for treatment at a hospital in Vichy, France, and finally transferred to a hospital in Bordeaux, France. All three areas of injury proved to be debilitating; his right wrist received minor nerve damage, right knee and ankle obtained minor scarring, and his left thigh received a 10-in long, 2-in wide scar, leaving him with a prominent limp.

Private Hammond and an assorted company of wounded servicemembers left Brest, France on the U.S. Army Transport Ship Maui on 15 January 1919, arriving at Camp Merritt, New Jersey on 25 January. Private Hammond was set for hospitalization at Camp McClellan, Alabama; after recovery, Honorably Discharged from said location on 17 February 1919.

Serving with [E] Company, 2nd Battalion, 366th Infantry Regiment, 183rd Infantry Brigade, 92nd Infantry Division, Private Alex Hammond demonstrated his valor during a firefight near Lesseux on 4 September, 1918. This is his story.

Saint-Dié Sector – 4 September 1918

August 1918:

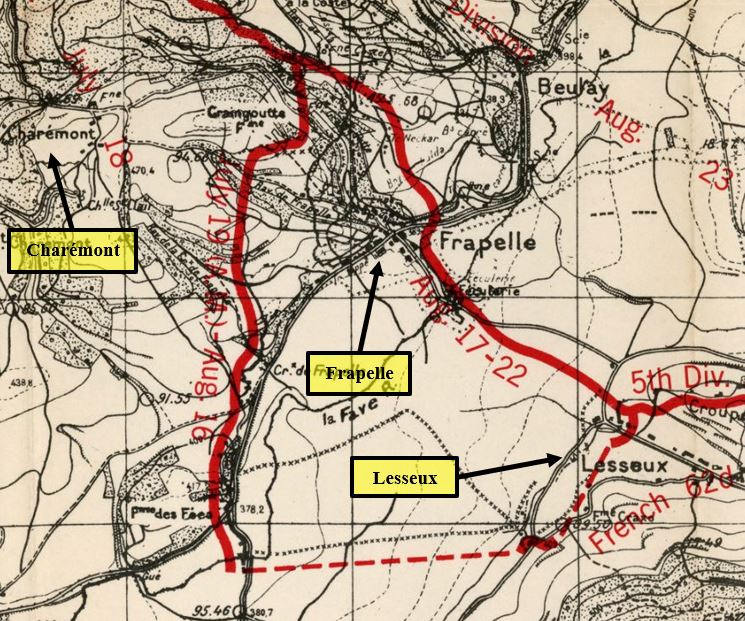

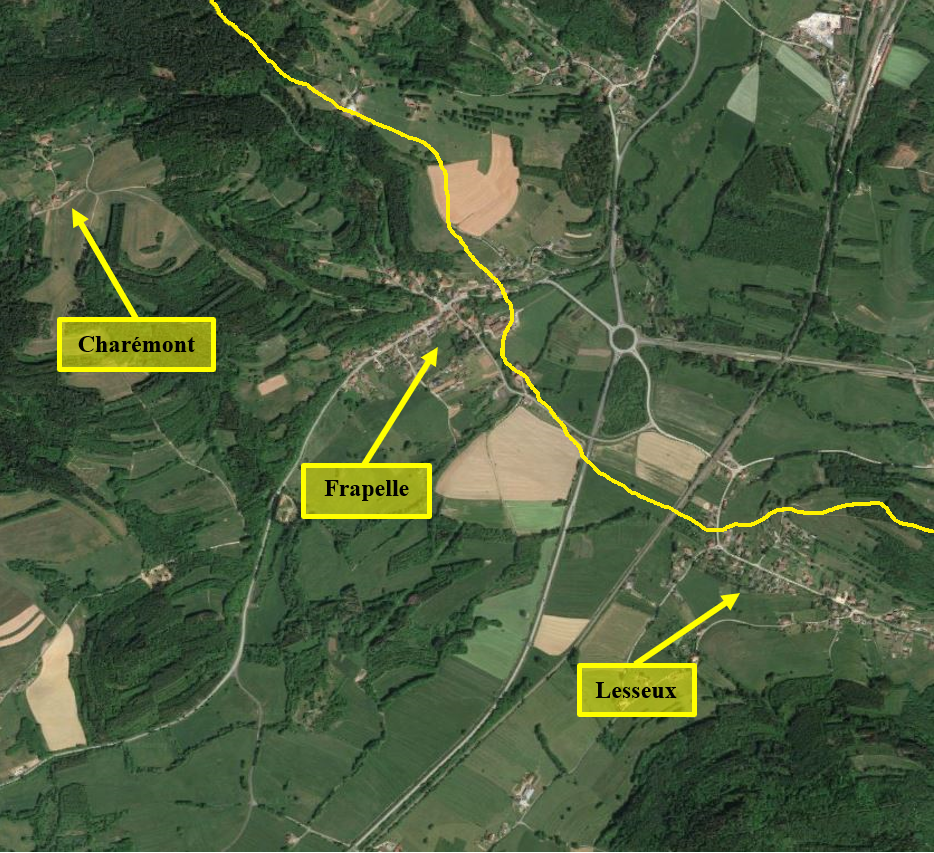

While the initial German offensive of 1914 made great gains through Belgium and Northern France, the naturally defensible terrain of the Vosges Mountains along the (then) Franco-German border made offensive operations through this area virtually impossible. Thus, for almost the entire duration of the war, combat along this front consisted of little more than sporadic raids, artillery strikes, and, on special occasion, aerial combat. Though the conditions of this battlefield were hardly safe in the conventional sense, compared to the rest of the Western Front this entire region was deemed a “safe” front for inexperienced or low-strength units. This changed once the sector came under the control of the American 5th Division, under the command of the French XXXIII Corps, whose fresh troops were eager for a fight.

Captured by the Germans in 1914, the small town of Frapelle had long been a weak-point in the Allied lines. Controlling the southern end of the Saales Pass, Frapelle was an ideal staging area for future attacks through the mountains. Further, its capture would also allow the 5th Division to close-up a sizable gap in their frontline, which would prevent exploitation of this gap by the Germans and allow the Allies to establish uninterrupted lines of communication from one end of the Saint-Dié Sector to the other. All of these things considered, the Americans decided that Frapelle was too good of a target to pass up. Thus, in a surprise attack on 17 August, the 6th Infantry Regiment, 5th Infantry Division, fell upon the German defenders in the town and claimed it for their own.

Furious, the Germans vowed to make the Americans pay for this transgression. Almost as soon as the American infantry took Frapelle, practically every German artillery piece, machine-gun, and plane within the region turned to attack them. Heavy artillery cannons and first-rate Prussian troops were also summoned from outside of the sector to reinforce the second-rate Alsatian Guards that had previously held Frapelle. However, for five days the 5th Division held onto their gains, and succeeded in establishing a continuous frontline along the entire Saint-Dié front until 22 August, when the sector passed to the 92nd Infantry Division.

During their time in the Saint-Die sector, the 92nd Division encountered some of the German Army’s most fearsome weapons. Gas attacks in particular were so severe that Allied commanders decided it was necessary to give the men additional instruction in the use of their protective equipment – though as a later report revealed, the Small-Box Respirator model gasmasks issued to the Division were not an appropriate fit for the men of the 92nd Division, forcing many to go without adequate gas protection. Other horrors encountered included regular artillery shelling, grenade attacks, trench raids and, when the weather permitted, German planes conducted virtually unopposed bombing-runs or directed accurate fire from cannons and machine-guns hidden high within the surrounding mountains. It didn’t take the 92nd Division long to realize this – the division suffered its first casualties as a result of enemy fire on 23 August, while the 366th Infantry Regiment was relieving the 6th Infantry Regiment in Frapelle.

1-3 September 1918:

On the night of 31 August and morning of 1 September, the Germans launched an all-out assault on the American frontline. The rattling of machine-guns, pops of rifle fire, and shouts of scared men filled the cool mountain air through the night, except when they were smothered by the earth-shattering booms of artillery. The night grew bright with the flash of firearms, explosions, and streaks of liquid-fire that burst forth from German flamethrowers. Though this initial assault was repelled with French artillery support, the Germans returned that afternoon following a nearly three-hour long bombardment and a firefight raged across the slopes of Ormont, west of Frapelle, until the Germans again ceded the field. That night, patrols from the 92nd Division reported that the Germans had left their forward trenches unguarded, signaling that they were anticipating a general engagement. However, the 92nd Division would disappoint them; though the men of the division were ready to take the fight to the enemy, their commanding officers gave stern orders to not escalate the conflict.

Over the next two days, the Germans shelled the 92nd Division’s lines both day and night. High-explosive and chemical shells saturated the 92nd Division’s lines so thoroughly that, in at least one recorded incident, and officer and several men were unable to detect the signature scent of mustard gas due to the sheer amount of smoke that had filled their dugout. As a result of this and other incidents, the 92nd Division made the aforementioned discovery that their gas defense was painfully inadequate, and would likely remain so regardless of discipline unless better protective equipment was obtained. The German infantry did not attack on 2 September, but did attempt a raid-in-force on 3 September, which was repelled. During the fighting that day, Second Lieutenant Aaron Fisher of the 366th Infantry Regiment became the first member of the 92nd Division to distinguish himself in service, when he chose to remain in the field and coordinate the defense despite suffering from severe wounds. His actions that day set the standard for the 366th Infantry Regiment, which would serve admirably throughout the war.

4 September 1918:

The fourth of September saw another large raid strike the 92nd Division. A minenwerfer barrage focused on the 366th Infantry Regiment’s trenches in and around the village of Lesseux claimed the lives of several men and caused a section of their trenches to literally collapse, burying some men in the ruins of their trench. However, the Germans gave the American soldiers no time to recover. Descending on the dazed and confused men with a well-armed raid-in-force, the Germans were surprised to find that a handful had not only survived the bombardment, but had quickly assumed a strong defensive disposition, even though many suffering from severe wounds.

One of these outstandingly courageous men was Private Alex Hammond from Alabama. Already nursing a debilitating wounds from a gunshot and grenade shrapnel, Hammond suddenly found himself in close-combat with the Germans. However, despite his condition, Private Hammond refused to retreat. He remained at duty until the Germans finally gave up and and surrendered the field.

For his courage and commitment to duty, Hammond was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross under General Orders No. 139 and the French Croix de Guerre with Silver Gilt Star under Order No. 17.470 “D.”

Several other members of the 92nd Infantry Division were recognized for their actions near Lesseux on September 4, 1918. Their names and links to their own Personal Narratives are included below.

Sergeant (Then-Private) Roy A. Brown, [E] Company, 366th Infantry Regiment.

Corporal Van Horton, [E] Company, 366th Infantry Regiment.

Private First-Class William Clincey, [F] Company, 366th Infantry Regiment.

Private George W. Bell, [E] Company, 366th Infantry Regiment.

Private Edward L. Merrifield, [E] Company, 366th Infantry Regiment.

According to related reports, Hammond appeared to suffer from bouts of mental instability after his return from service. In the summer of 1921, Hammond was accused, and found guilty, of second-degree murder, in which he killed his significant other and attempted to take his own life afterwards. Hammond was sentenced to fifteen years of hard labor in the Wetumpka State Penitentiary in Wetumpka, Alabama; before commencing his sentence, he was (rather publicly) rejected from the Alabama Gold Star database due to his race and criminal record, though committee members did not appear to reject all other African American applicants in the following years. At the beginning of his sentence, Hammond surrendered his personal effects (including his DSC and CDG) to his state-issued attorney, who then misplaced said item(s)- along the while, his estrangement from family members seemed to gradually worsen.

Hammond was injured in a prison truck crash involving a private vehicle in November of 1929, significantly worsening his general physical condition; throughout his sentence, he attempted to gain parole, but was only issued temporary periods of separation. Hammond developed pulmonary tuberculosis in the late 1920s and was transferred to the prison’s Tuberculosis Hospital in May of 1931, dying on 5 June 1931.

His family did not claim his body, he was buried in the Wetumpka State Penitentiary Cemetery; he never married or had children.