Joe Williams

Military Honor(s):

Distinguished Service Cross

Citation: The President of the United States of America, authorized by Act of Congress, July 9, 1918, takes pleasure in presenting the Distinguished Service Cross to Private Joe Williams (ASN: 2169035), United States Army, for extraordinary heroism in action while serving with Company E, 366th Infantry Regiment, 92d Division, A.E.F., near Lesseux, France, 4 September 1918. Private Williams was a member of a combat group which was attacked by 20 of an enemy raiding party advancing under a heavy barrage and using liquid. The sergeant in charge of the group was killed and several others, including Private Williams, were wounded. Nevertheless, this soldier, with three others, fearlessly resisted the enemy until they were driven off.

Life & Service

- Birth: , Acton, AL, United States

- Place of Residence:

- Race/Ethnicity: African American

- Death: , United States

- Branch: Army

- Military Rank: Private

- Company: [E]

- Infantry Regiment: 366th

- Division: 92nd

At the time of his Act of Valor, Private Joe Williams was serving with [E] Company, 366th Infantry Regiment, 92nd Infantry Division under the command of the French XXXIII Corps. The following is his story.

The Saint-Dié Sector – 4 September 1918

August 1918:

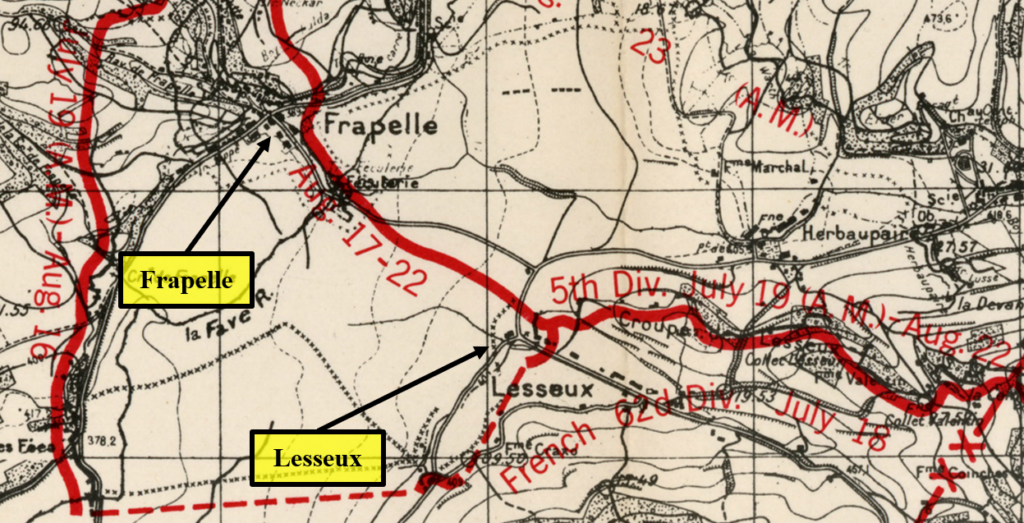

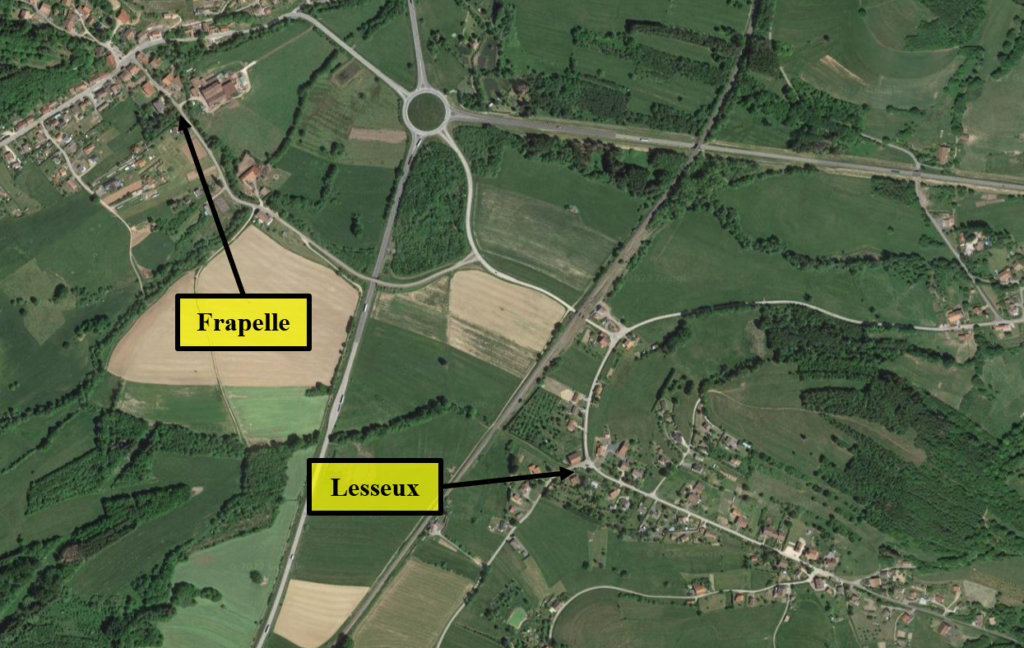

Though the Vosges Mountains had been the backdrop for some of the Great War’s earliest battles, both German and French military commanders quickly realized that the rugged terrain in this region made offensive operations against an entrenched foe highly impractical. Thus, as early as the Autumn of 1914, the warring powers developed a mutual understanding that those sections of the Western Front that passed through these mountains could be transformed into relatively safe “rest sectors” for inexperienced or war-weary units. This is why one such sector, located in close proximity to the French city of Saint-Dié-des-Vosges, was selected as a training ground for the fresh-faced American doughboys that began to trickle into France in 1917. However, these same American soldiers played a pivotal role in undoing the peace of the Saint-Dié Sector when, on 17 August, 1918, the 6th Infantry Regiment, 5th Infantry Division, seized the town of Frapelle from the second-rate Alsatian Guards who had been entrusted to guard the sector.

This sudden and unexpected violation of the Saint-Dié Sector’s peace enraged the Germans, who levelled virtually ever gun in the sector, as well as some from outside of the sector, on the American soldiers and their French allies. For the better part of a week, the 5th Infantry Division sustained heavy bombardment with high-explosive and gas shells until they were relieved by the African-American 92nd Infantry Division over the course of 21-25 August. If the thunder of the German guns hadn’t already made it clear to the yet-untested 92nd Division that their deployment to the Saint-Dié Sector would not be an easy one, the razing of Frapelle on 23 August made the trial-by-fire that awaited them all too apparent. This is because this bombardment, which occurred while the 366th Infantry Regiment was relieving the 6th Infantry Regiment from their frontline positions in and around Frapelle, caused the 92nd Divisions first casualties as a result of enemy fire in the Great War, including 2 men killed and another 6 badly wounded. The 92nd Division spent the last week of August, 1918, fending-off German raiders and aircraft while under constant artillery bombardment.

1-3 September 1918:

The night of 31 August initially seemed like any other. The German artillery opened fire on schedule and the men of the 92nd Division, having grown accustomed to life under the German guns, took to their protective dugouts to wait-out the bombardment. However, when the German infantry attacked en-masse in the ensuing hours, it became apparent that this would be no ordinary night. Through the early morning hours of 1 September, 1918, vicious nocturnal combat raged across the 92nd Division’s front until the Germans were finally repelled by artillery fire from the French XXXIII Corps (the 92nd Division’s own 167th Field Artillery Brigade was still in training at this time; consequently, the 92nd Division had to rely on friendly units for artillery support). As the sun rose over the war-torn Saales Pass, the toll that this failed attack had taken on the Germans became apparent, as their dead littered the mountain slopes and valley. However, the 92nd Division did not escape this fight unscathed – 4 members of the 92nd Division had been killed, including First Lieutenant Thomas Bullock (the first officer of the 92nd Division to be killed in action), and another 34 men were badly wounded.

That afternoon, the German Infantry attempted to attack the 92nd Division’s lines once again. From 1230 Hours (12:30 PM) to 1500 Hours (3:00 PM), the Germans fired nearly 12,000 shells into the 92nd Division’s trenches. Following this intense bombardment, a bloody firefight broke out on the slopes of Ormont, but the Germans were ultimately repelled by the combined efforts of the 365th and 366th Infantry Regiments. That night, patrols from the 92nd Division were able to reach the German’s frontline trenches, which they found were unmanned – a sign that the Germans were expecting the 92nd Division to counterattack. However, the commanding officers of the 92nd Division issued strict orders for their men to maintain their current positions. Thus, while the German artillery continued to pelt the Allied lines with high-explosive and chemical shells throughout 2 September, 1918, the 92nd Division held the line. The following day, the Germans attempted to provoke the 92nd Division to action by mounting a large raid on the 366th Infantry Regiment’s lines, but this attack did little more than present Second Lieutenant Aaron Fisher the opportunity to become the first member of the 92nd Division to be recognized for his service.

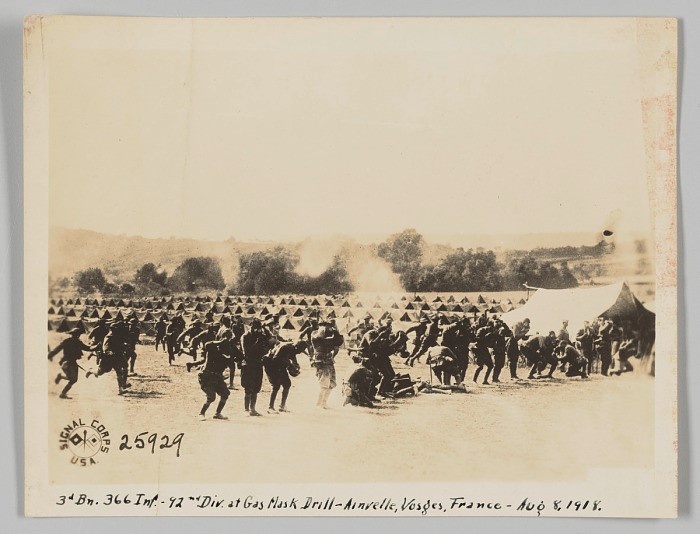

3rd Battalion, 366th Infantry Regiment, 92nd Division at Gas Mask Drill in Ainville, Vosges, France, August 8, 1918.

This isn’t to say that the German offensive was completely toothless. Due to the sheer extent to which the German artillery had saturated the Saint-Dié Sector with chemical weapons, cracks began to emerge in the 92nd Division’s gas defense. Foremost among these problems was the simple truth that the Small-Box Respirator gasmasks that were standard-issue across the American Expeditionary Forces did not fit many of the men. As a consequence, roughly 1,500 members of the 92nd Infantry Division, despite their otherwise commendable gas discipline, did not possess adequate protective equipment to defend themselves from dangerous chemical agents. Further, smoke from smoldering high-explosive residue and burning debris had grown so thick in parts of the Saint-Dié Sector that it was sometimes difficult to even sense hazardous chemicals, including the notorious “mustard gas,” so-named for its otherwise distinctive odor. In at least one recorded incident, this very problem was directly blamed when a pair of officers and several enlisted men were gassed in their dugout. The problems discovered in the 92nd Division’s gas defense during their time in the Saint-Dié Sector continued to plague them throughout the war, especially since the order placed for new Tissot masks was seemingly never fulfilled.

4 September 1918:

On 4 September the Germans launched another large raid on the 366th Infantry Regiment’s lines in and around the village of Lesseux. A devastating opening barrage with artillery and minenwerfers, which collapsed a section of the 366th Regiment’s frontline, buried several men and killed or wounded many others. Giving their disoriented victims no time to recover, a cohort of well-armed German raiders opened fire with rifles and flamethrowers while grenadiers lobbed hand-grenades into the American trenches. However, despite this horrific demonstration of German shock tactics, a handful of surviving soldiers were able to rally and push the Germans back. One of these men was Private Joe Williams, who worked with 3 other men to establish a strong defensive response that stalled the German assault in the space between the trenches. As soon as this happened, the firefight turned decidedly in the Americans’ favor, and the Germans were driven back to their own lines. Because of the actions of men like Private Williams, the Germans were never able to penetrate the 366th Infantry Regiment’s lines during their time in the Saint-Dié Sector.

A German gas attack on soldiers during World War One. Dated 1914. (Universal History Archive/UIG via Getty Images) – Colourized.

For his part in the defense of Lesseux, Private Joe Williams was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross under General Orders No. 143. He received this medal on December 21, 1918, near the city of Pont-à-Mousson in Northeastern France.

Several other members of the 92nd Infantry Division were awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for actions near Lesseux on September 4, 1918. Their names and links to their own Personal Narratives are included below.

Sergeant (Then-Private) Roy A. Brown, [E] Company, 366th Infantry Regiment.

Corporal Van Horton, [E] Company, 366th Infantry Regiment.

Private First-Class William Clincey, [F] Company, 366th Infantry Regiment.

Private George W. Bell, [E] Company, 366th Infantry Regiment.

Private Alex Hammond, [E] Company, 366th Infantry Regiment.

Private Edward L. Merrifield, [E] Company, 366th Infantry Regiment.