The American 92nd Infantry Division, known as the Buffalo Soldiers, was formed in 1866 at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. The all-black 10th Cavalry Regiment had earned their names from the Native American tribes they encountered during the Indian Wars, but the nickname soon spread to all African-American regiments including the 10th, 24th, 25th, and (Second) 38th Infantry Regiments.

The American 92nd Infantry Division, known as the Buffalo Soldiers, was formed in 1866 at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. The all-black 10th Cavalry Regiment had earned their names from the Native American tribes they encountered during the Indian Wars, but the nickname soon spread to all African-American regiments including the 10th, 24th, 25th, and (Second) 38th Infantry Regiments.

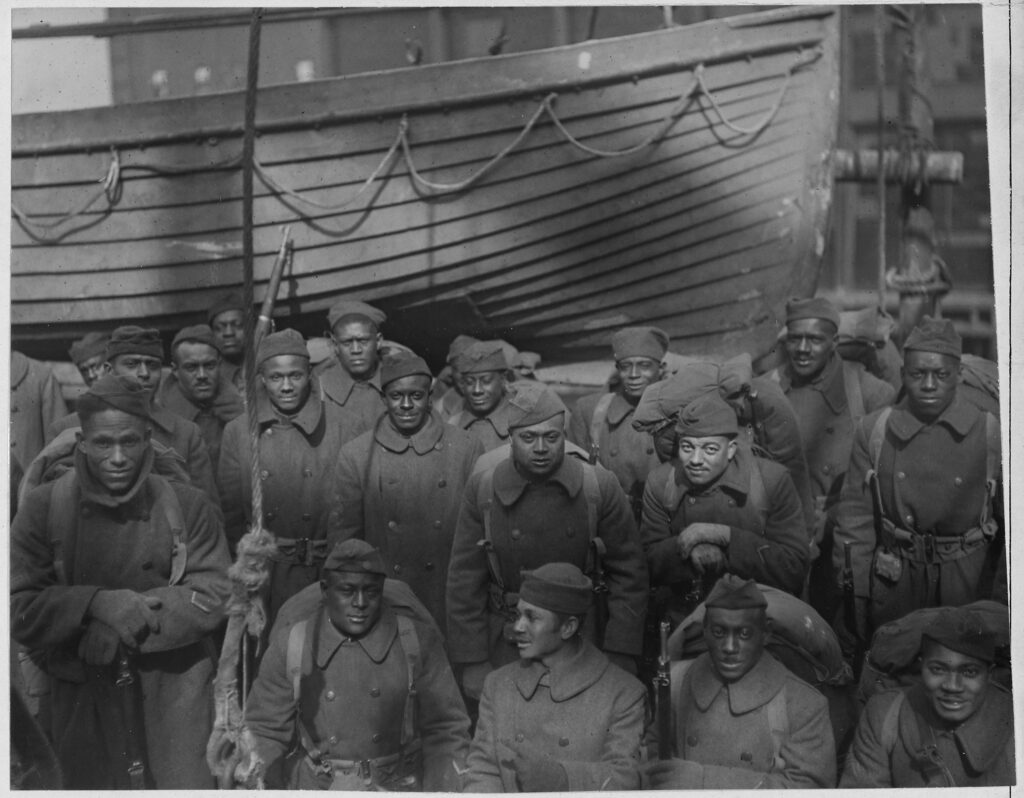

On 29 November 1917, the 92nd Division was formed from African-American men who were willing to serve for a country that discounted them at every turn. The “all-negro” outfit was commanded by Major General Charles C. Ballou, whom oversaw the African-American officer cadets at Fort Des Moines Officers Training Camp in Des Moines, Iowa. However, despite African-American officers being trained at Fort Des Moines under Ballou, United States Army policy determined that no African-American could rise above the rank of Captain. Subsequently, the majority of the 92nd Divisions command laid in the hands of Caucasian officers. In May 1918, the 92nd was brought to full strength and was concentrated at Camp Upton, New York prior to embarking to France.

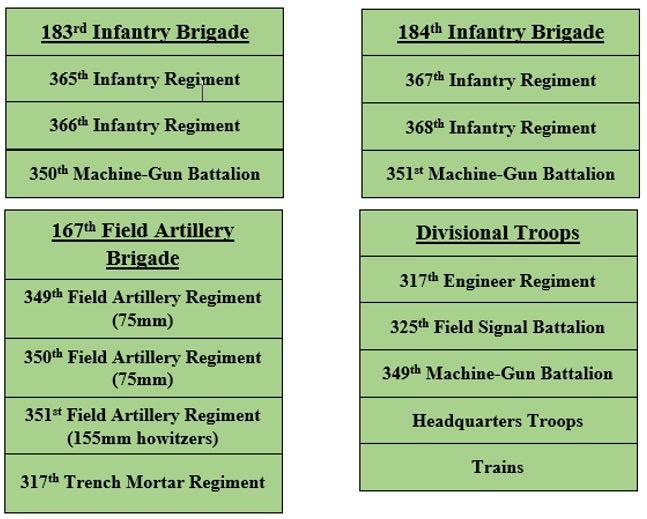

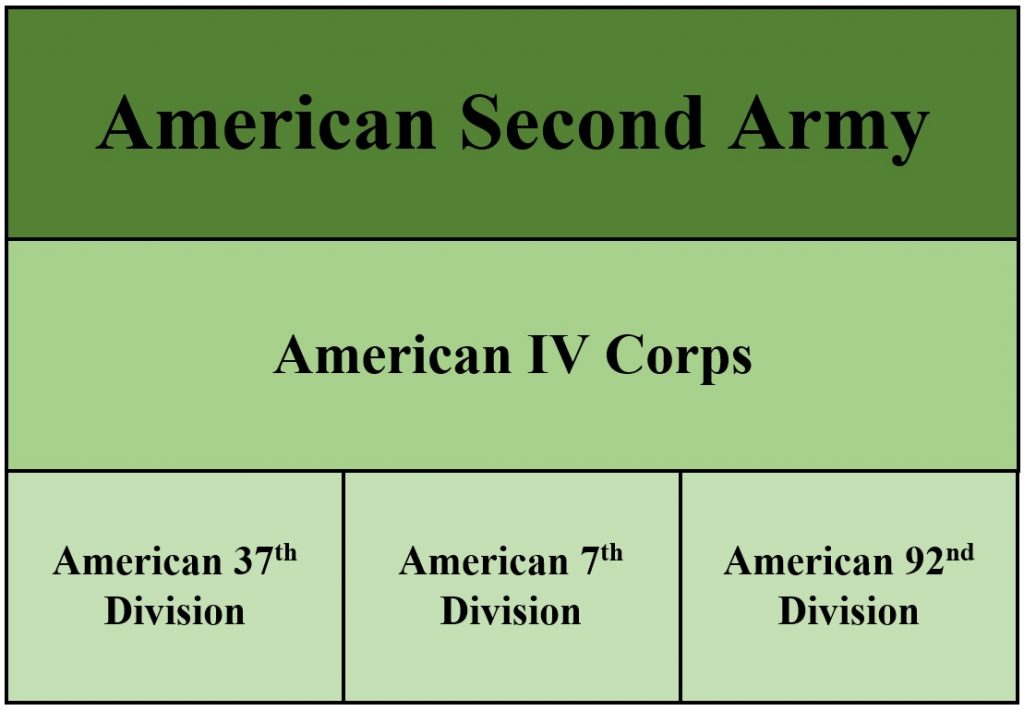

Organization of the 92nd Division:

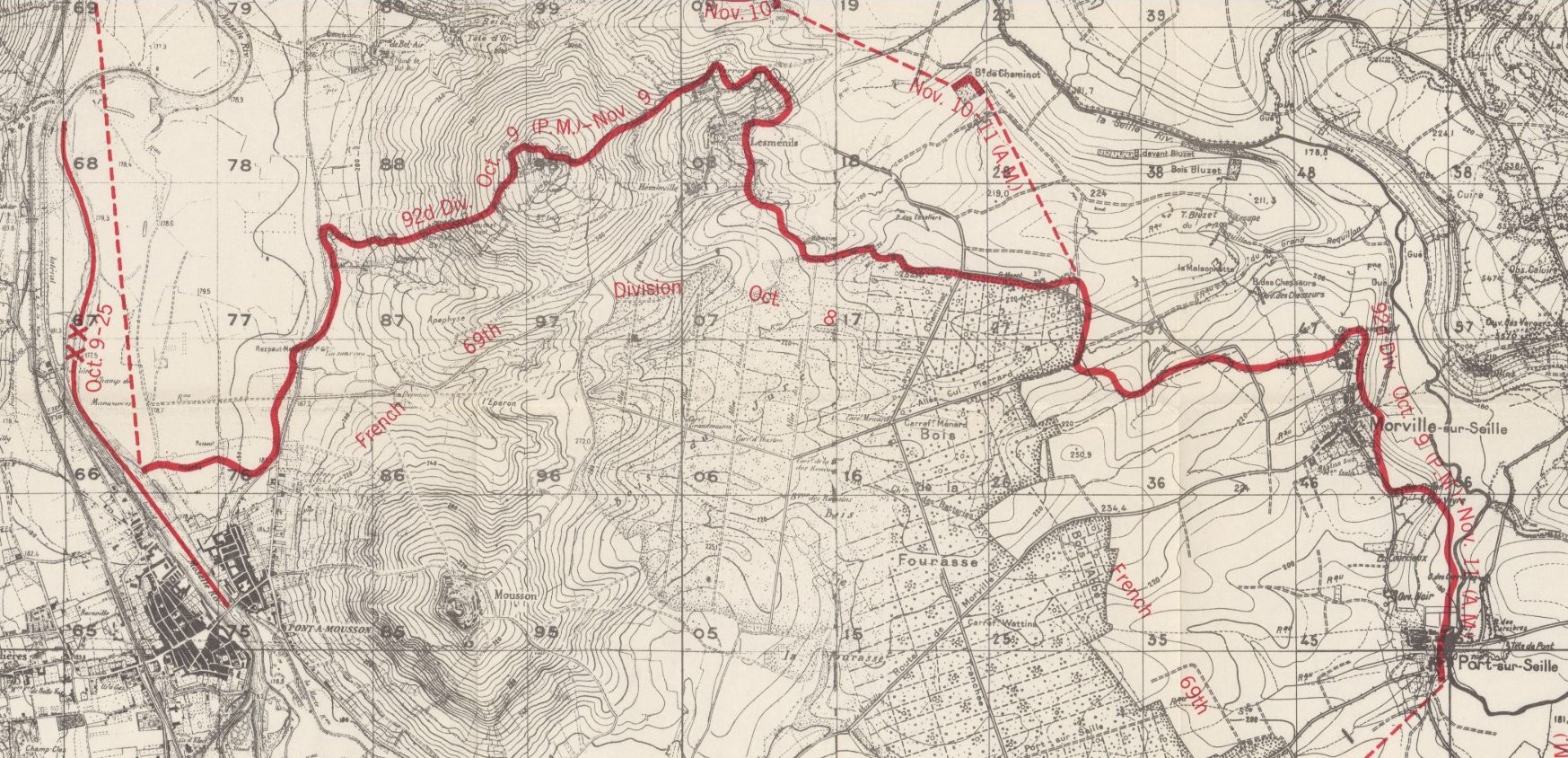

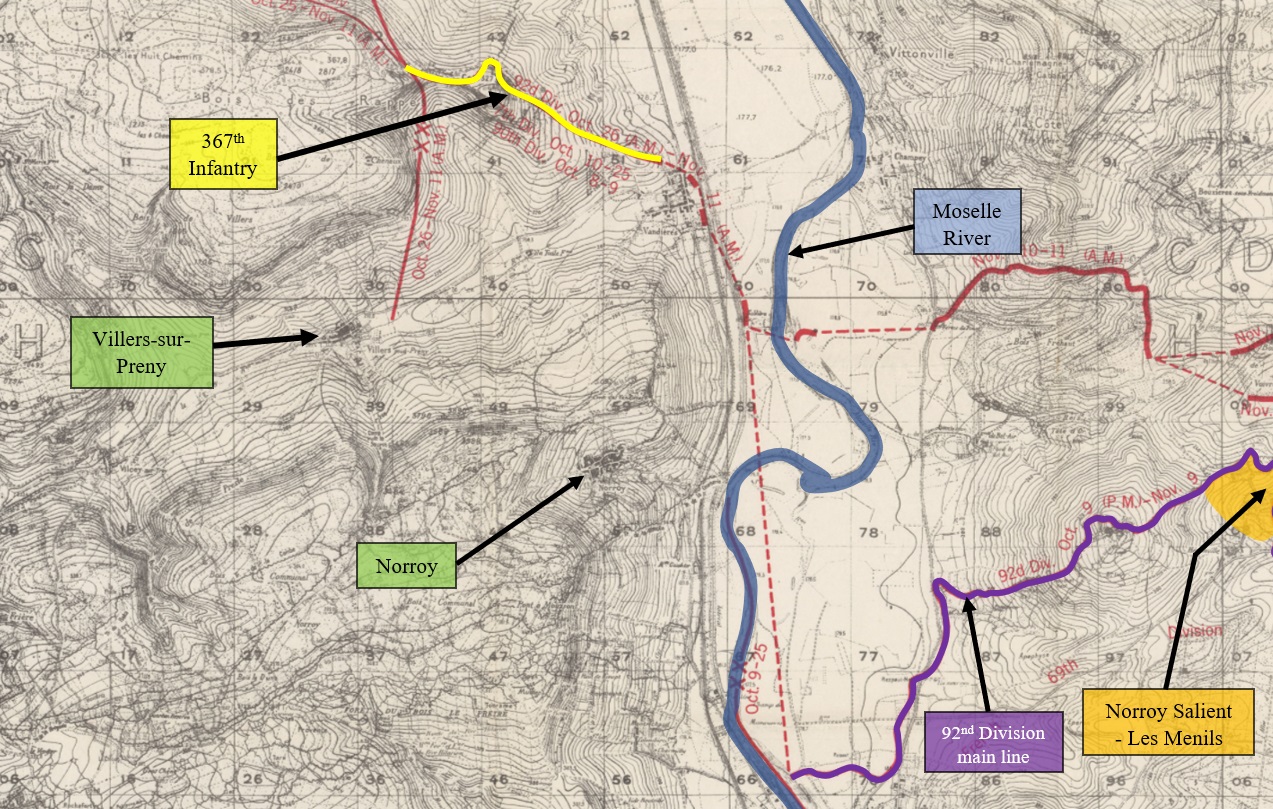

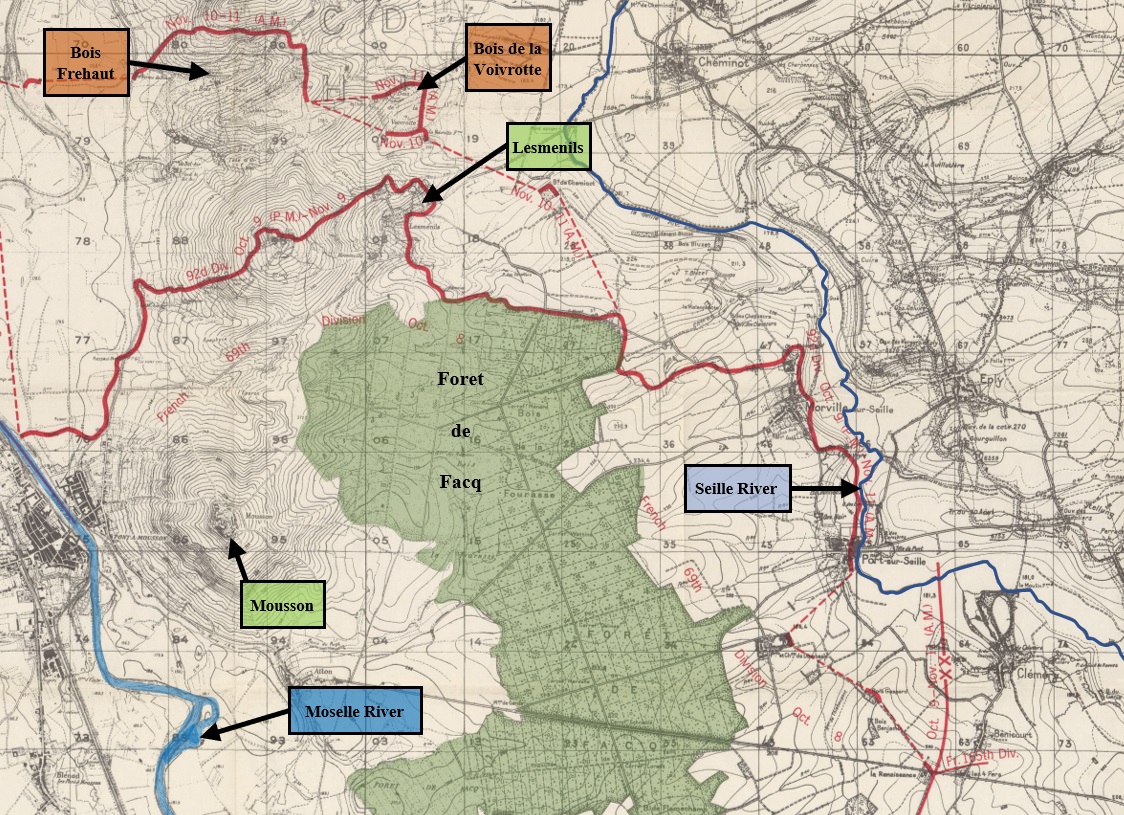

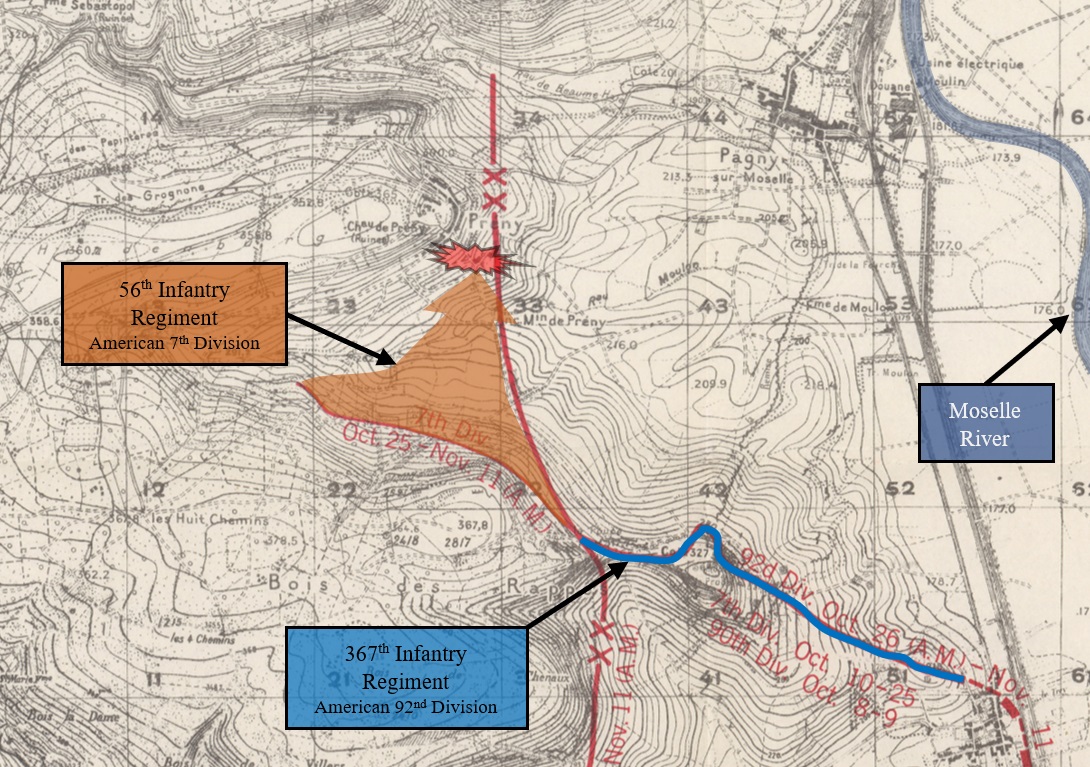

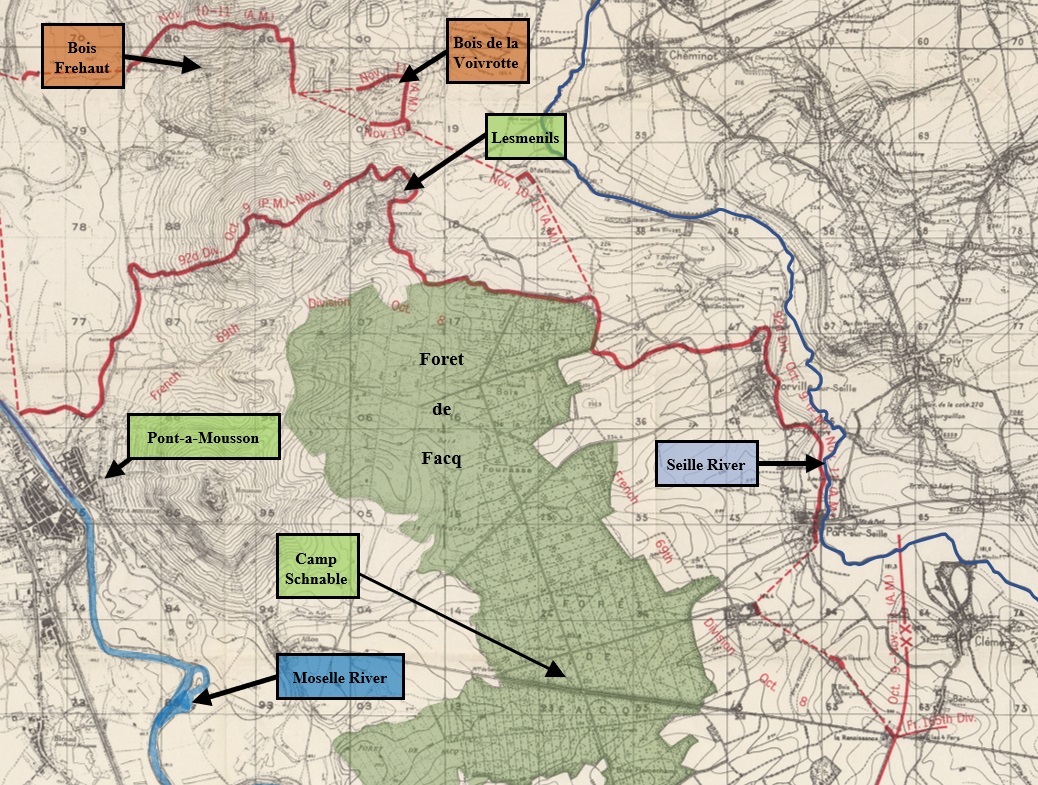

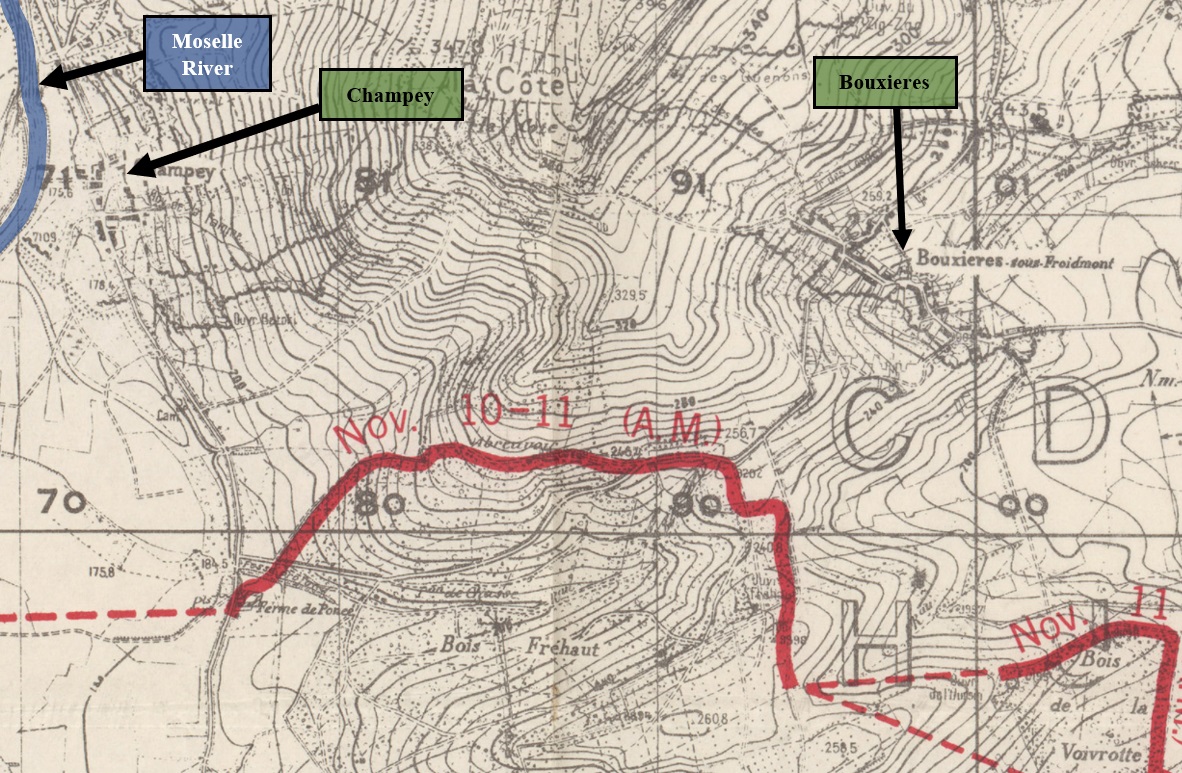

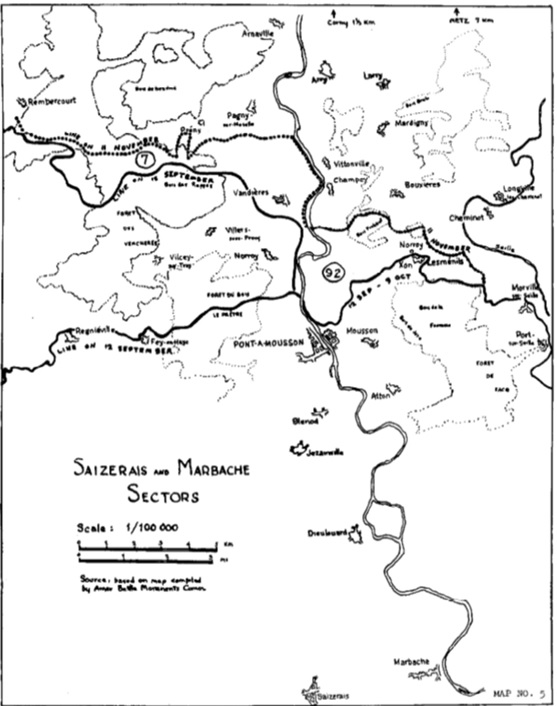

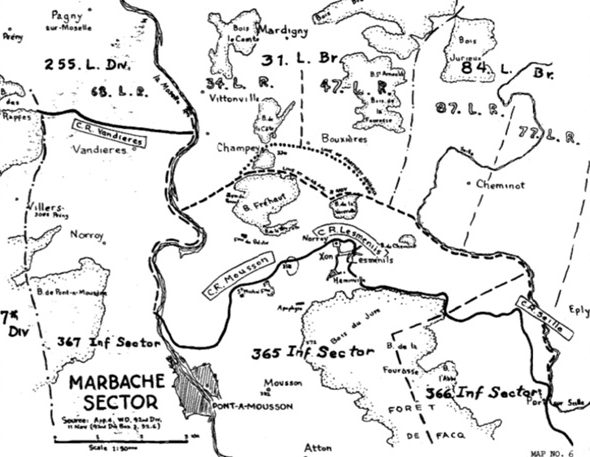

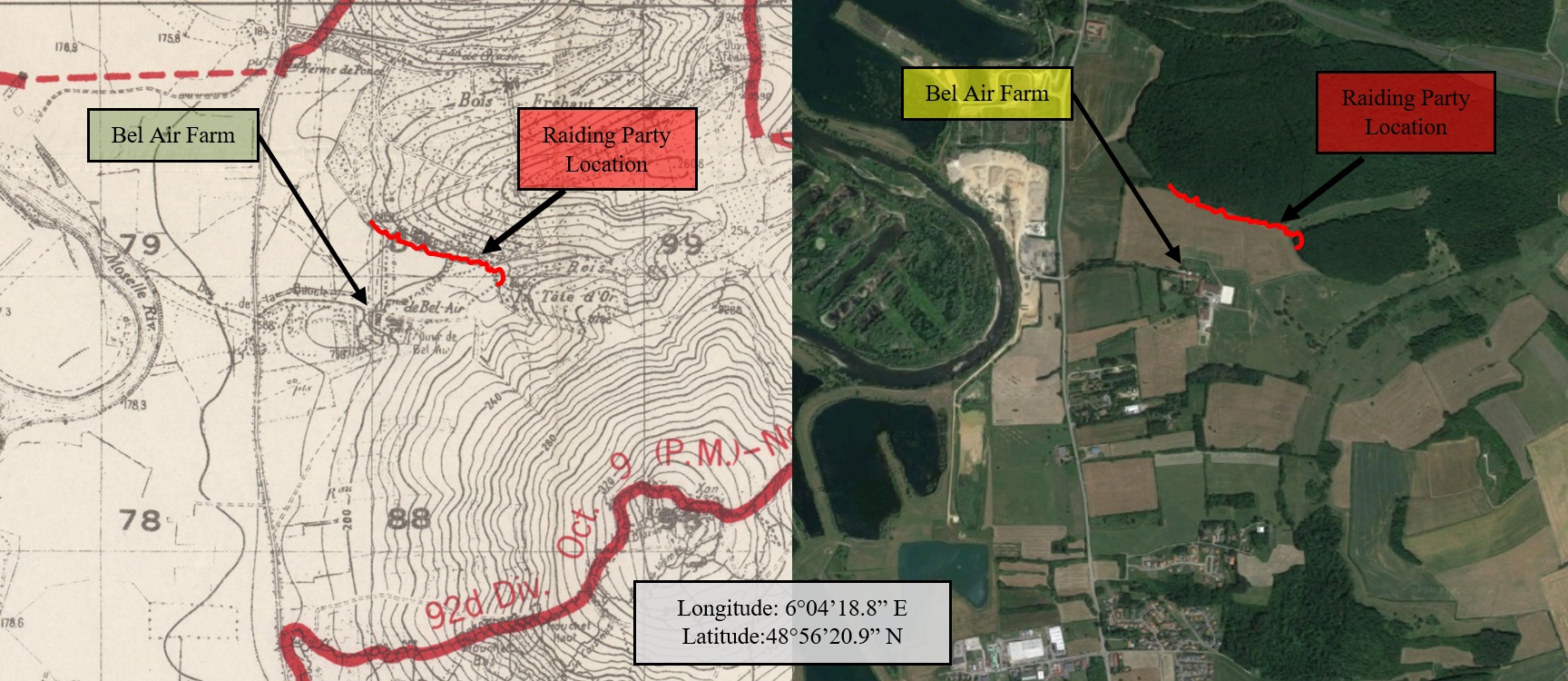

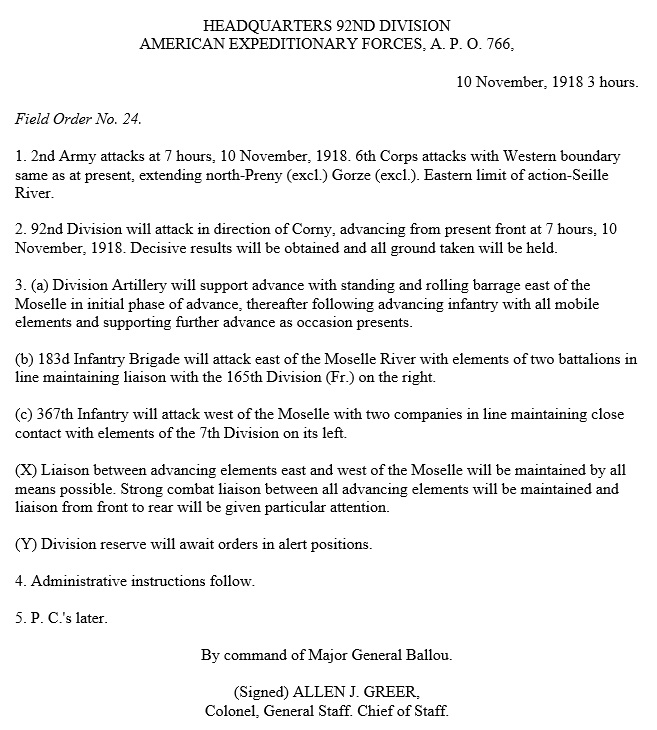

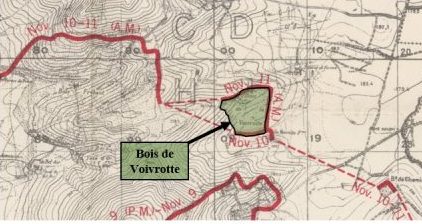

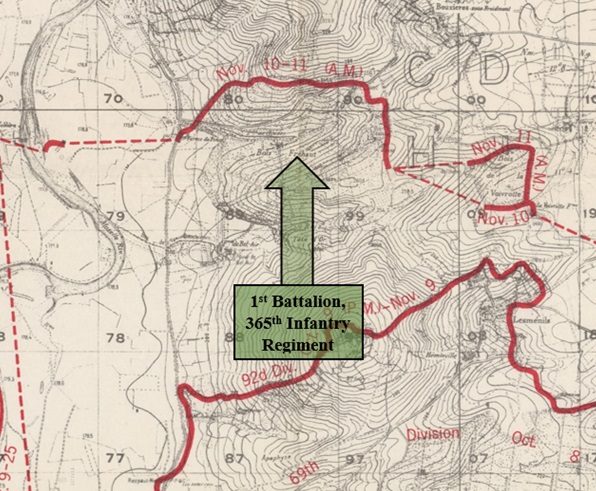

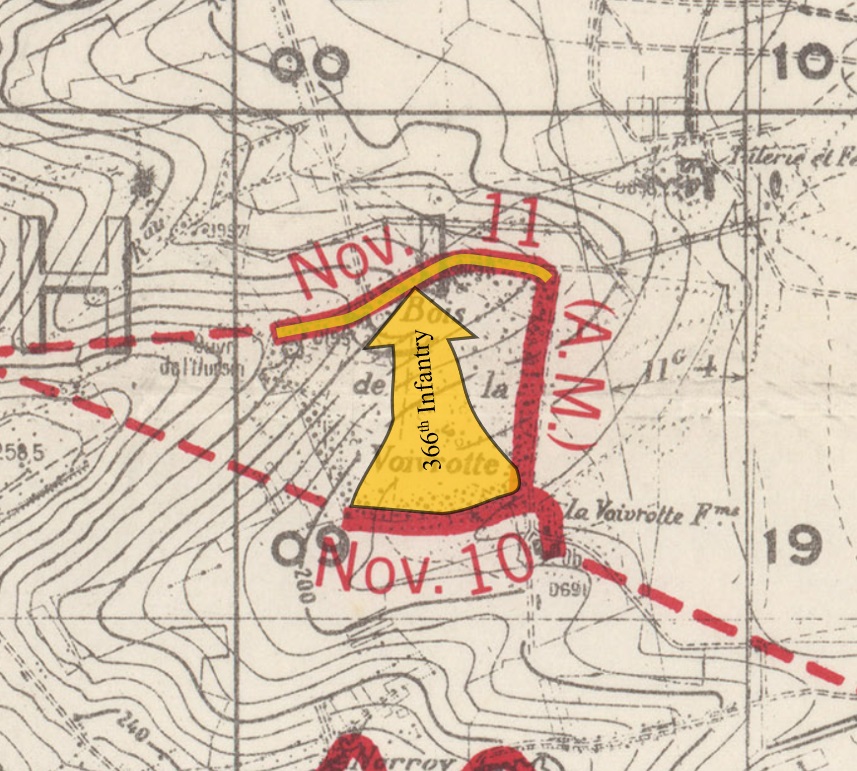

The 183rd and 184th Infantry Brigades participated in battles of the Saint Die Sector (Vosges, France) from 29 August to 20 September 1918, and the Marbache Sector (Lorraine, France) from 9 October to 11 November 1918.

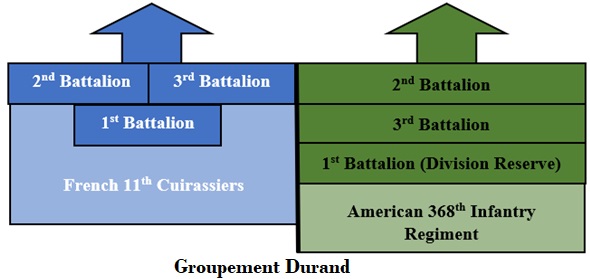

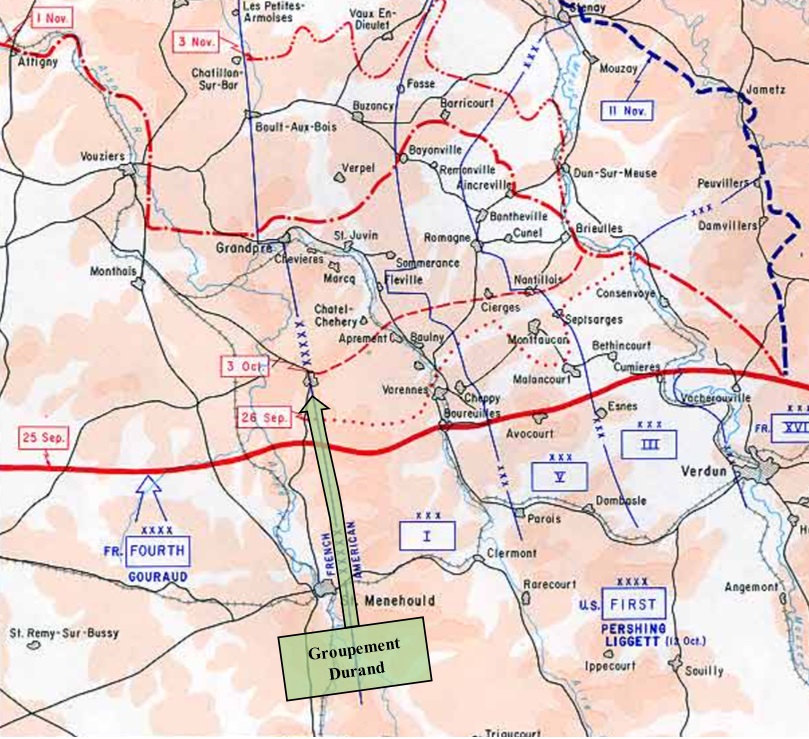

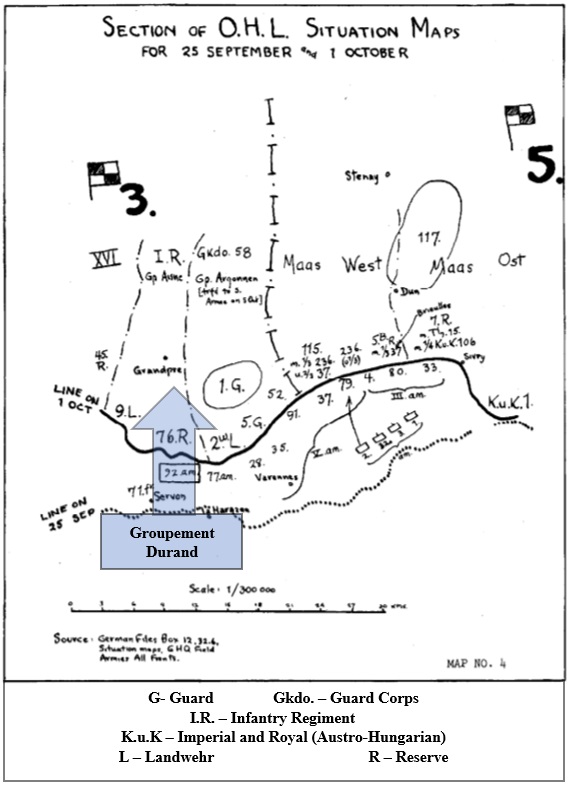

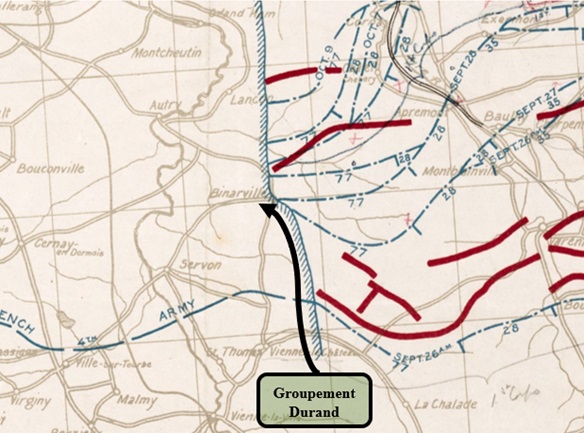

Note: The only exclusion to this was the 368th Infantry Regiment who had also participated in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive from 26 September to 4 October 1918 as part of a Franco-American liaison group known as Groupement Durand (or the lesser known designation of Groupement Rive Droite).

The American 92nd "Buffalo Soldiers" Division

Photo Gallery

![Company [M], 365th Infantry Regiment, 183rd Infantry Brigade, 92nd Division](https://gsr.park.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/CoM365.jpg)

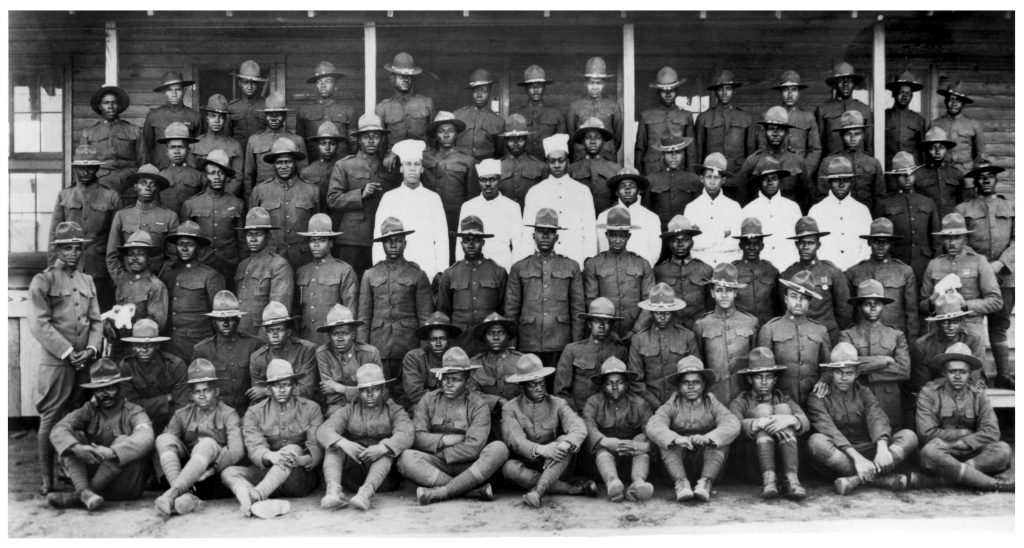

Company [M], 365th Infantry Regiment, 183rd Infantry Brigade, 92nd Division

A Photo of Members in the 92nd Division

“Medical Detachment 365th Infantry. A Representative Group Of Medical Officers And Their Field Assistants. This Branch Of The 92nd Division Rendered Most Valorous Service.”

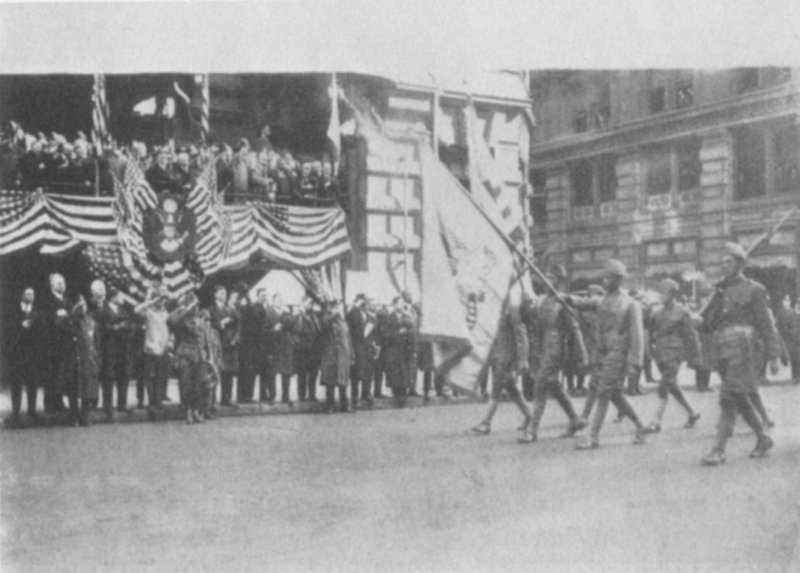

Members of the 367th Infantry Regiment marching up 5th avenue with the colors presented to them by the Union League Club of New York City, 1918.

“The ‘Buffaloes’ marching in review before Governor Whitman, before the presentation of the colors in front of the Union League Club, New York City,” 1918

Men of the 367th Infantry Regiment, the ‘Buffaloes,’ sing the National Anthem before the Union League Club, New York City, 1918.

“‘Moss’s Buffaloes’ (367th Infantry), Reviewed By Governor Whitman After Flag Presentation In Front Of Union League Club, New York.”

Most African American Servicemembers Were Pushed Into Duties Of Physical Labor Roles, Rather Than Combat Roles. “Heroes Of The Brawny Arm Whose Service Was No Less Effective Than That Of The Combatants. A Detail Of Negro Railway Builders Engaged On The Line From Brest To Tours.”

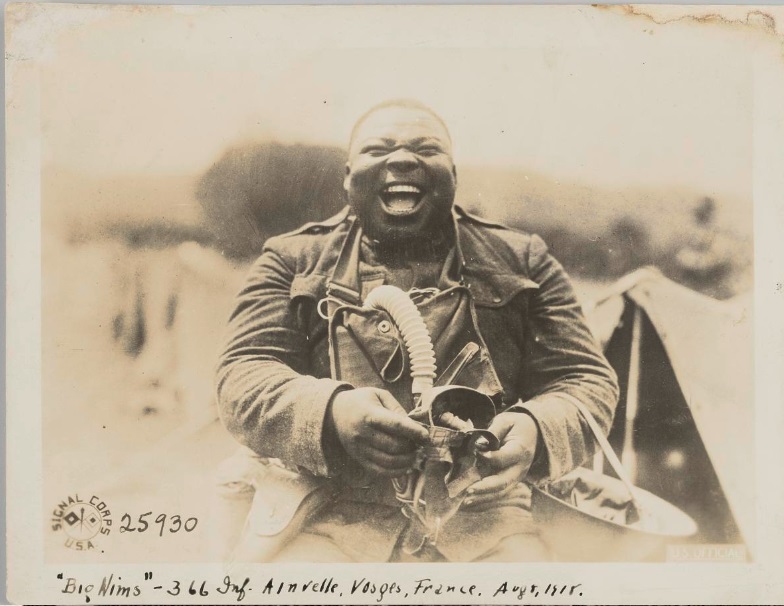

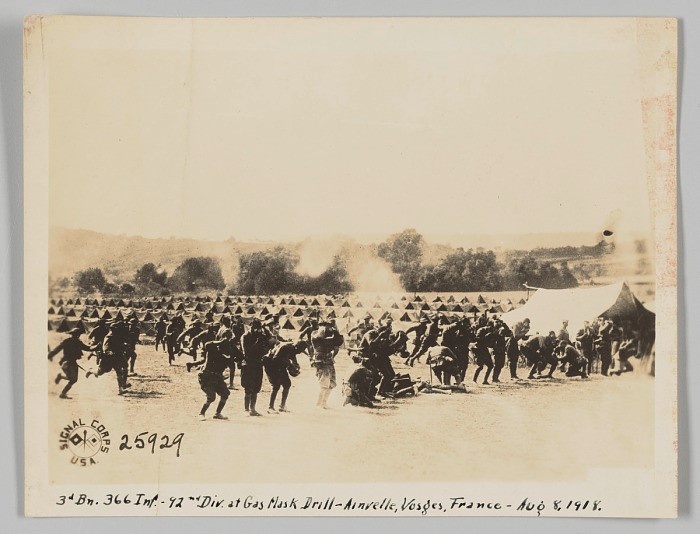

3d Bn. 366 Inf. 92nd Div. at Gas Mask Drill – Ainville, Vosges, France – Aug. 8, 1918

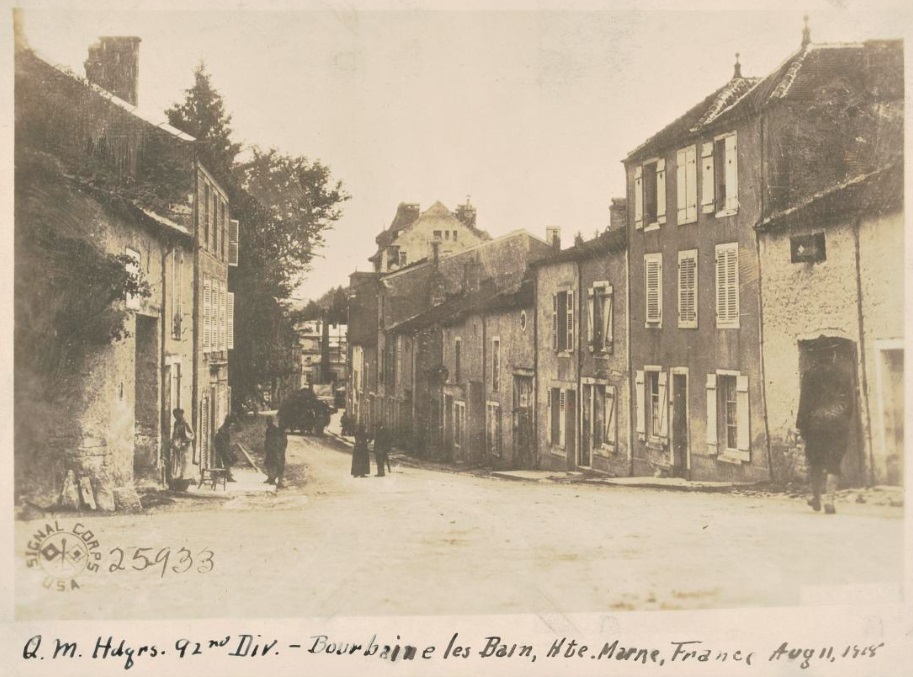

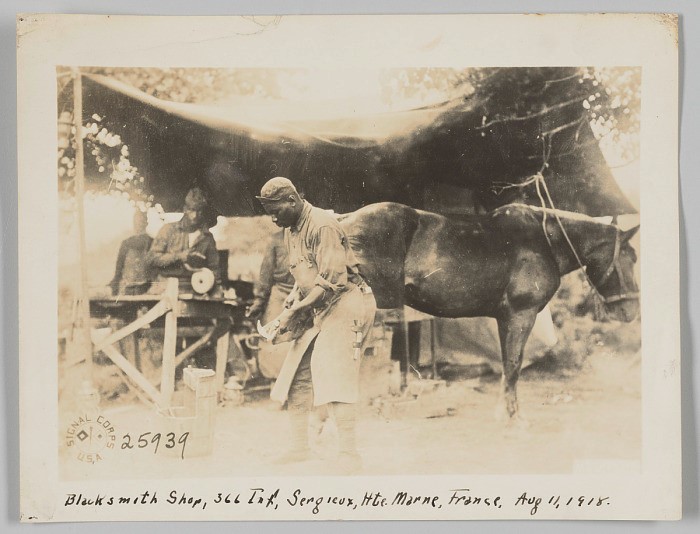

Blacksmith Shop, 366 Inf. Sergieux, Hte. Marne, France. Aug. 11, 1918

366 Inf. 92 Div. Ainville, Vosges, France – Aug. 11 1918

Truck Train unloading 366 Inf. Bruyers, Vosges France. Aug. 12, 1918

“Lieutenant Robert L. Campbell, Negro Officer Of The 368th Infantry Who Won Fame And The D.S.C. [Distinguished Service Cross] In Argonne Forest. He Devised A Clever Piece Of Strategy And Displayed Great Heroism In The Execution Of It.”

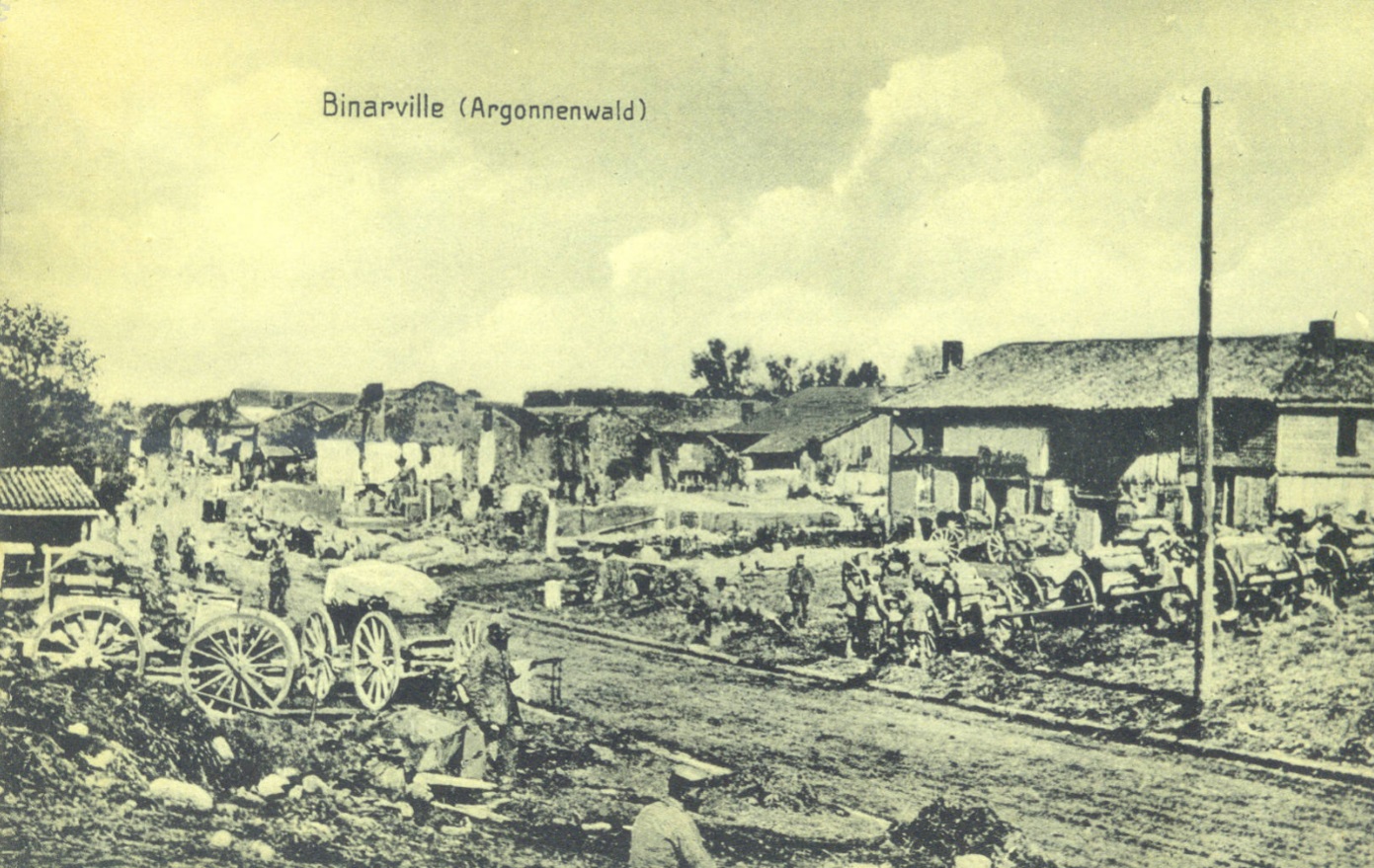

325 Field Signal Bn. 92nd Div. Stringing Lines – Binarville (Argonne) Oct. 1, 1918

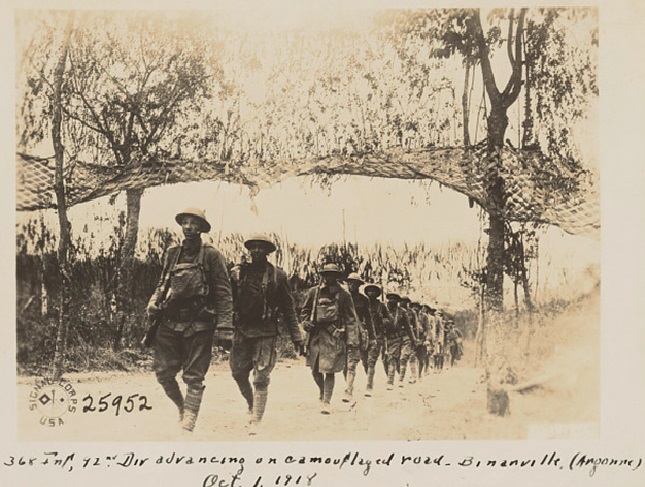

368 Inf, 92nd Div. advancing on camouflaged road – Binarville (Argonne) Oct 1, 1918

Watching “Hun” Planes – 317th Supply Train – Belleville, Oct. 1918

Mess 317 Supply Train – Belleville Meuse. Oct 12, 1918

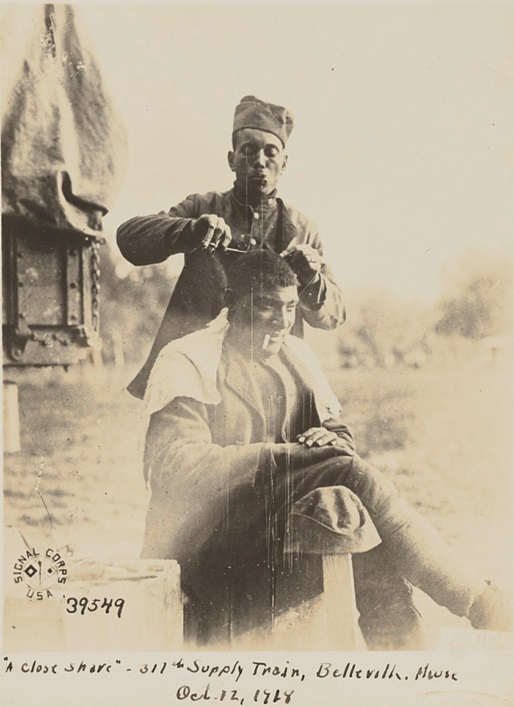

“A close shave” – 317th Supply Train, Belleville, Meuse. Oct. 12 1918

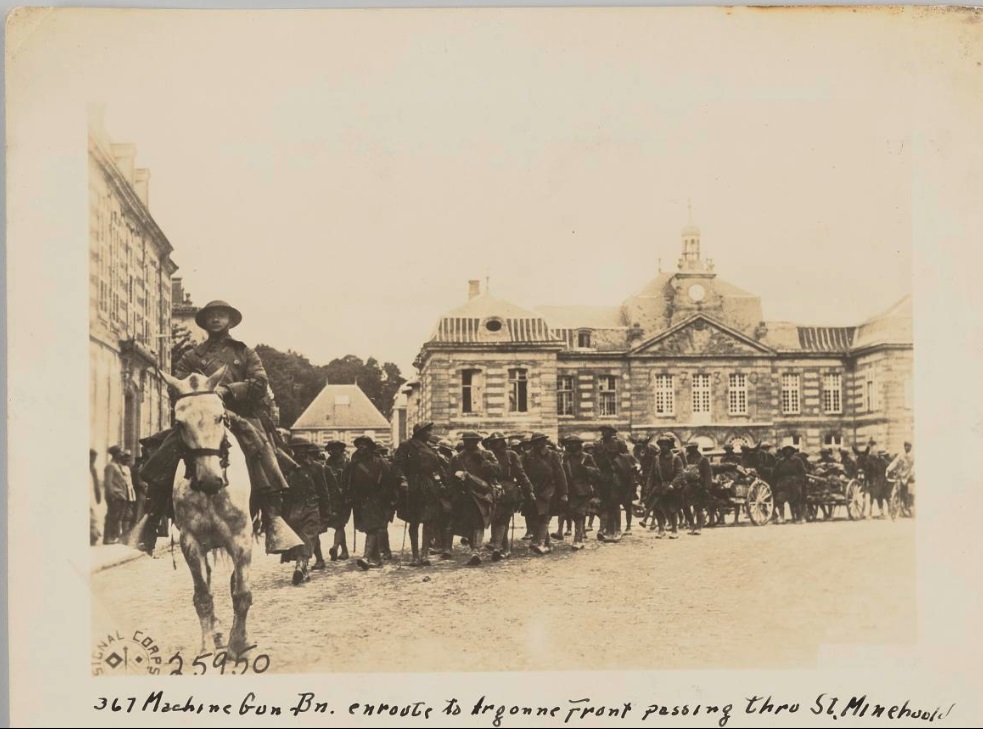

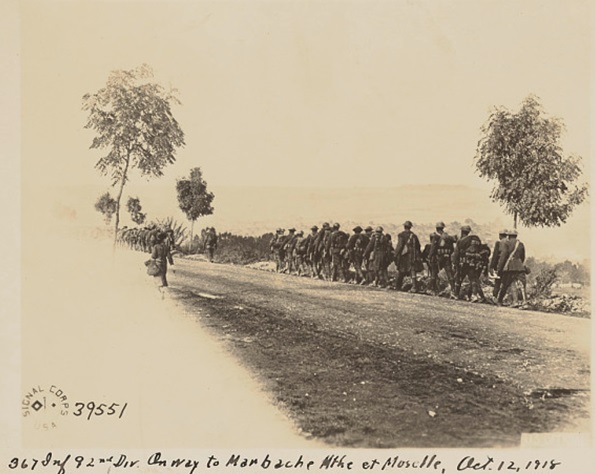

367 Infantry 92nd Div. On way to Marbache Mthe et Moselle, Oct. 12, 1918

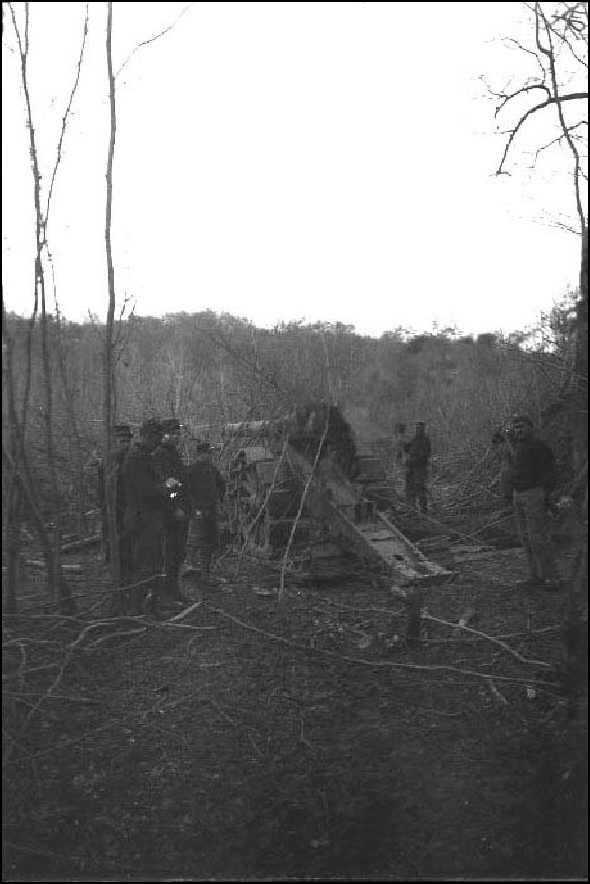

“Artillery At Work In A French Forest. This Was A Phase Of Operation In Which The Negro Units Of The 167th [Field Artillery] Brigade Distinguished Themselves In The Closing Days Of The War.”

Mess – M.T.R.S. men 92nd Div. Belleville, France Nov. 17, 1918

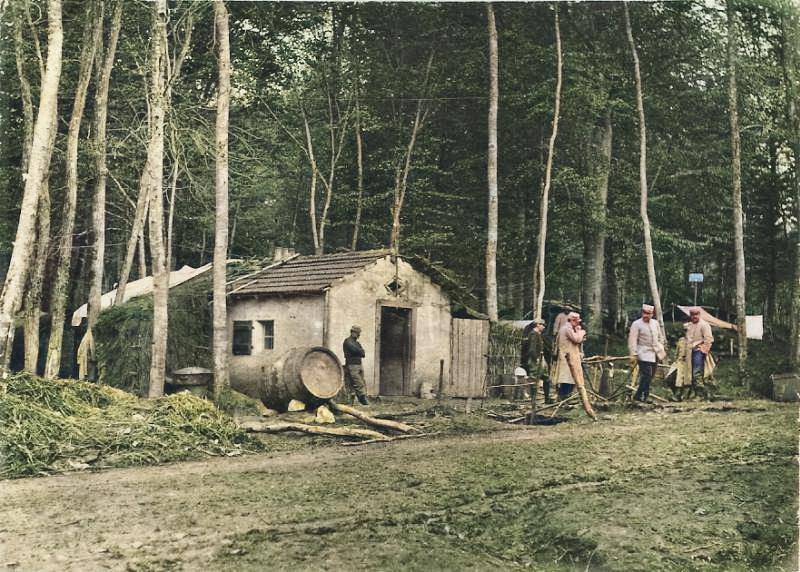

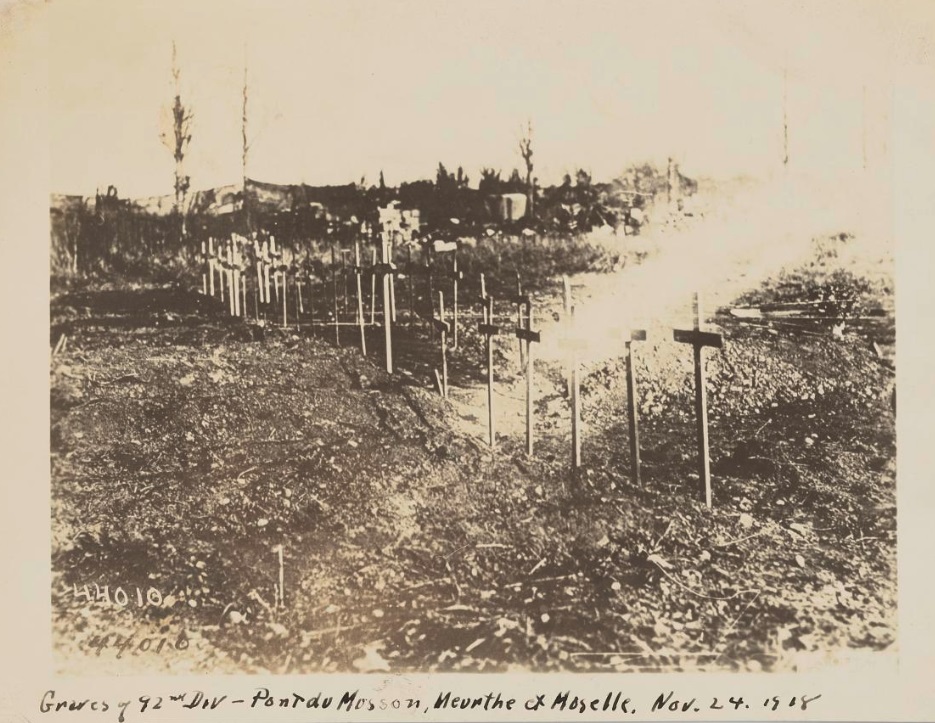

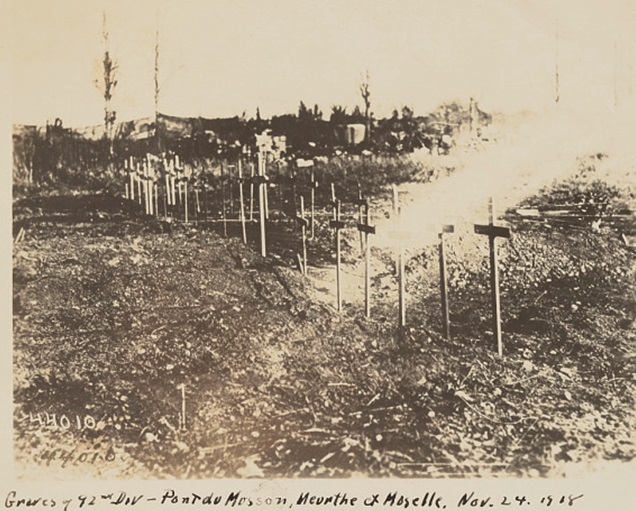

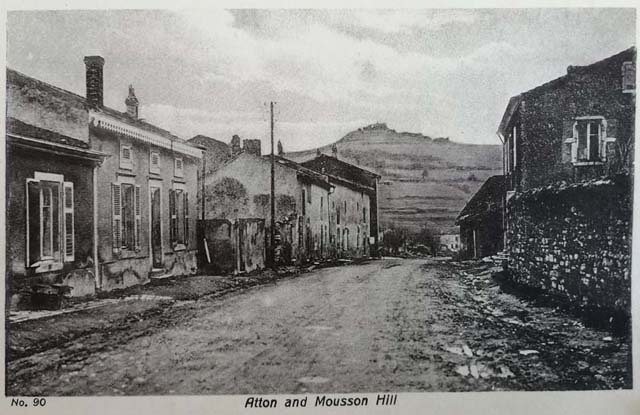

Graves of 92nd Division, Pont du Mousson, Meuthe et Moselle, Nov. 24, 1918

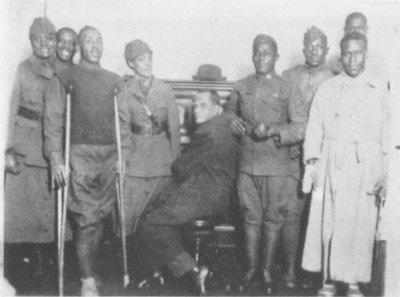

“Wounded Negro Soldiers Convalescing In Base Hospital. In The Picture Are Two Colored Women Ambulance Drivers.”

“General John J. Pershing, Commander in Chief, AEF, addressing officers of 92nd Division. Forwarding Camp, Near Le Mans, Sarthe, France,” 29 January, 1919.

Soldiers of the 325th Field Signal Battalion leaving for Camp Merritt after returning home on the transport “Ulua,” 7 February, 1919

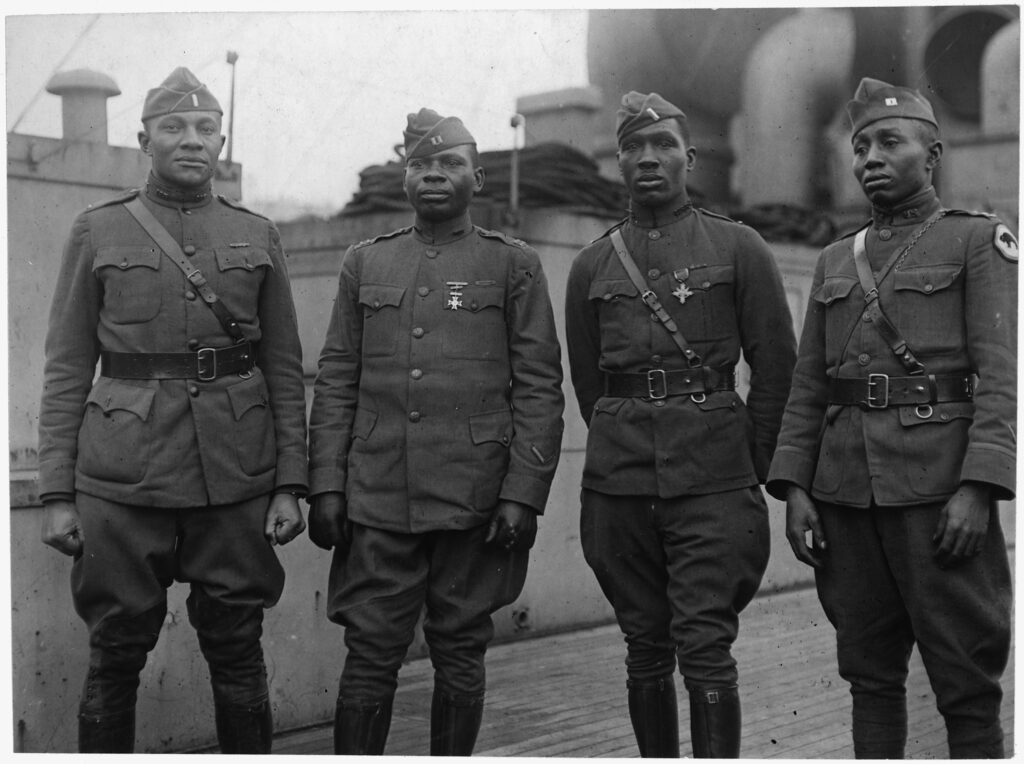

“Officers Of 366th Infantry [Regiment] Back on Aquitania. […] Left to right: Lieutenant C.L. Abbot, South Dakota; Captain Joseph L. Lowe, Pacific Grove, California; Lieutenant A.R. Fisher, Lyles, Indiana, winner of Distinguished Service Cross; Captain E. White, Pine Bluff, Arkansas.”

“Part of Squadron ‘A’ 351st Field Artillery, troops who returned on the transport Louisville. These men are mostly from Pennsylvania.”

“Two soldiers of the 351st Field Artillery Regiment which returned on the “Louisville” receiving candy from the Salvation Army Lassies,” 17 February, 1919.

“Heroes Of 351st [Field] Artillery [Regiment] Greeting Friends After Debarking From The Transport Louisville.”

“The “Buffaloes” (367th Infantry), Returning To New York After Valiant Service In France. Their Colors Still Flying.”

“‘Buffaloes,’ 367th Infantry, return colors to Union League Club. Men drawn up in front of Union League Club just before the colors were returned.”

“Soldiers Who Distinguished Themselves At The Fortress Of Metz. Group Belonging To 365th Infantry Arriving At Chicago Station.”

“Returning From The War. Musicians Of 365th Infantry Leading Parade Of The Regiment In Michigan Boulevard, Chicago.”

“Soldiers Of 365th Infantry Marching Down Michigan Boulevard, Chicago. This Regiment Was Part Of The Celebrated 92nd Division Of Selective Draft Men.”

“Troopers Of The 10th Cavalry Going Into Mexico. These Heroic Negro Soldiers Were Ambushed Near Carrizal And Suffered A Loss Of Half Their Number In One Of The Bravest Fights On Record.”

“Tenth Cavalry Survivors Of Carrizal. Despoiled Of Their Uniforms By The Mexicans They Arrive At El Paso In Overalls. Lem Spillsbury, White Scout In Center. Each Soldier Has A Bouquet Of Flowers.”

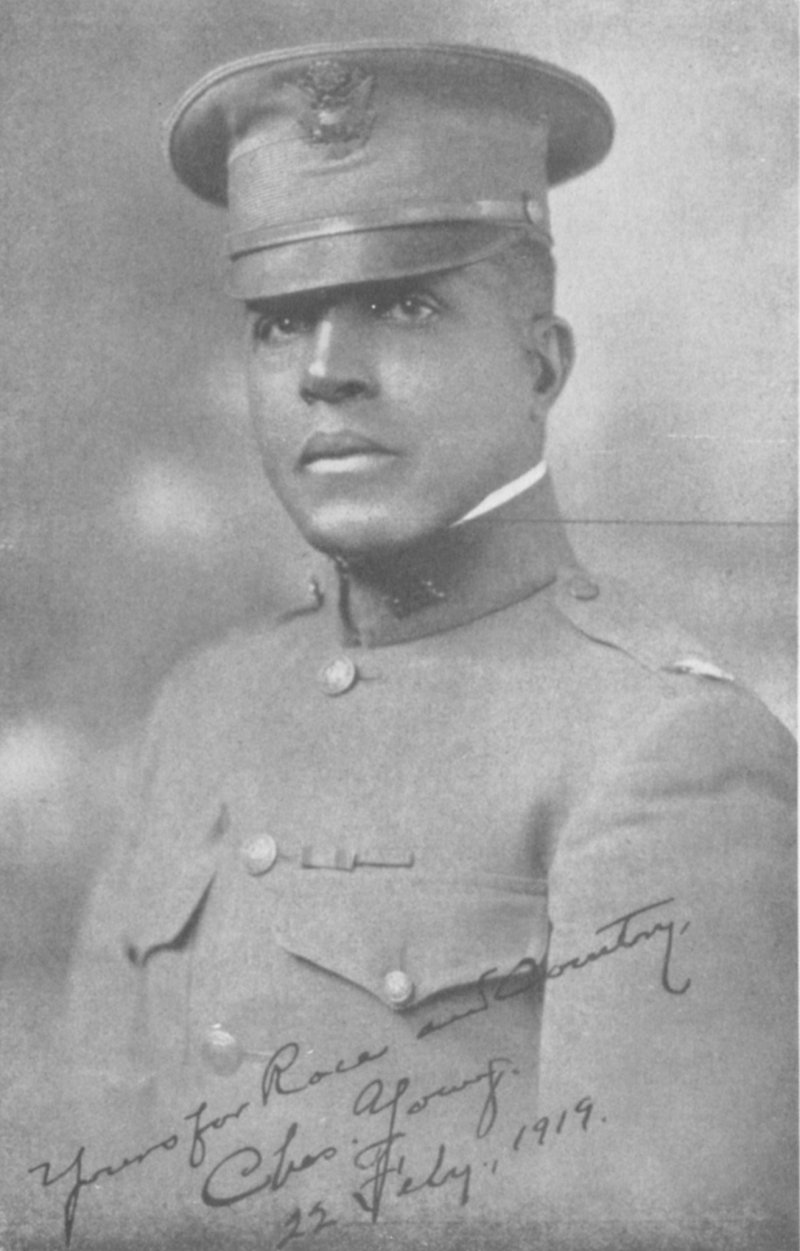

“Colonel Charles Young, Ranking Negro Officer Of The Regular Army. One Of Three Who Have Been Commissioned From The United States Military Academy At West Point. A Veteran Officer Of The Spanish-American War And Western Campaigns. Detailed To Active Service, Camp Grant, Rockford, Illinois. During The World War.” Photo Reads: “Yours For Race And Country. Charles Young. 22 July, 1919.”

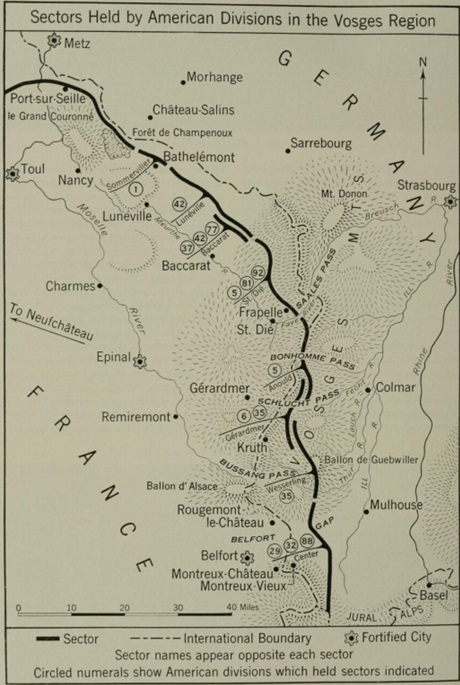

92nd Division - The Saint Die Sector

Source: “American Operations in the Vosges Front.” American Battle Monuments Commission. American Armies and Battlefields in Europe, n.d. https://www.abmc.gov/sites/default/files/publications/Section7.pdf. Page 422.

The Saint Die Sector formed part of the Southeastern tip of a battle that extended from the North sea to the border of Switzerland, where opposite of the Saint Die Sector laid Alsace and a strip of country riddled with mountains and forests. Natural and manmade physical barriers made any extensive military movement within the sector virtually impracticable, and therefor the sector was reasonably quiet. The Saint Die Sector was so notoriously quiet, in fact, that it was deemed a “rest sector” by the French and German armies.

The Saint Die Sector formed part of the Southeastern tip of a battle that extended from the North sea to the border of Switzerland, where opposite of the Saint Die Sector laid Alsace and a strip of country riddled with mountains and forests. Natural and manmade physical barriers made any extensive military movement within the sector virtually impracticable, and therefor the sector was reasonably quiet. The Saint Die Sector was so notoriously quiet, in fact, that it was deemed a “rest sector” by the French and German armies.

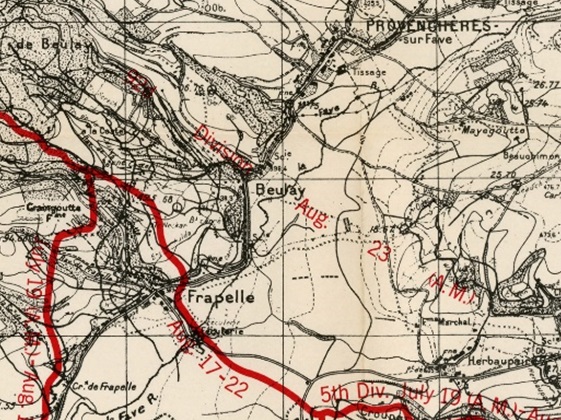

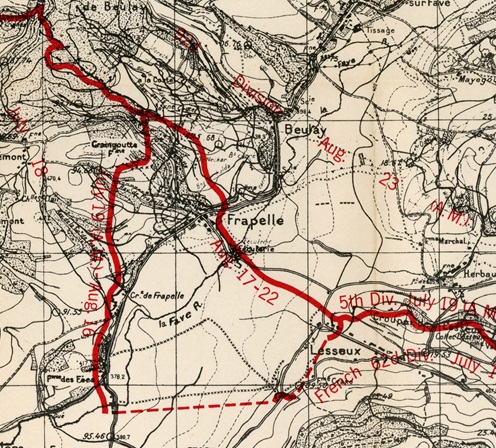

The frontlines of the Saint Die Sector was established 60 days after the opening of World War One and stretched about 25 kilometers wide. It laid within the Vosges Mountains (North of the town of Saint Die), and had controlled the Saales Pass. Although numerous attempts at assaulting various portions of the line had been made by the French and German armies, they had proven fruitless in the three years of combat prior to American intervention. The first change in the lines had occurred when the village of Frapelle was taken by the American 5th Infantry Division during the middle of August 1918.

Frapelle controlled an important high and the loss of the village had threatened the German railroad systems used to transport troops, supplies and messages along the frontlines in Southeast Alsace. To compensate for this loss, the Germans rapidly moved its Prussian troops to replace the bewildered Alsatian Guards while simultaneously providing the sector with more artillery and heavy machine-guns.

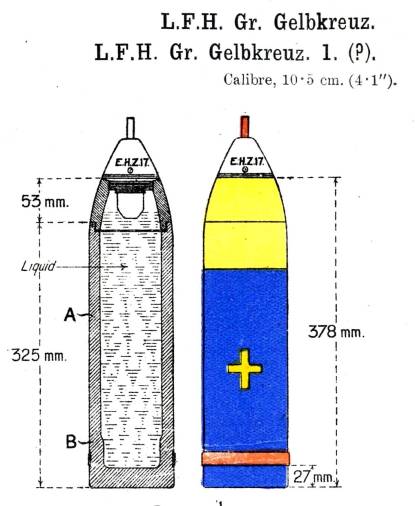

On 16 August 1918, the Prussian troops attempted to retake control of Frapelle, but had ultimately failed in its endeavors against the 6th Infantry and French units of the 33rd Army Corps (which the American 6th Infantry Regiment was brigaded with). The German elements along its line had disrupted the once peaceful sector with an artillery barrage on the town of Saint Die with high explosive and gas artillery shells.

21 August 1918:

On 21 August 1918, advanced infantry elements of the 366th Infantry Regiment arrived in the Saint Die Sector and began relieving elements of the French 87th Division. During its relief, the 366th Infantry Regiment had been subjected to heavy German artillery that lasted around four hours. The town of Frapelle was devastated and “no wall in the entire town was left standing.”

During the night, the advance elements of the 366th Infantry Regiment were located in the trenches of the Saint Die Sector, commencing relief of the American 5th Division during which two men were killed with an additional six being wounded.

23 August 1918:

By 23 August 1918, the entire 92nd Division (excluding the 167th Field Artillery) had moved from the training area into the Saint Die Sector and were assigned to relieve the American 5th Division. The 92nd Division was affiliated with the French 87th Division, French XXXIII Corps, and had controlled its portion of the line until it was relieved by the French 20th Division. The German artillery that had been battering the line was slowly subsiding.

25 August 1918:

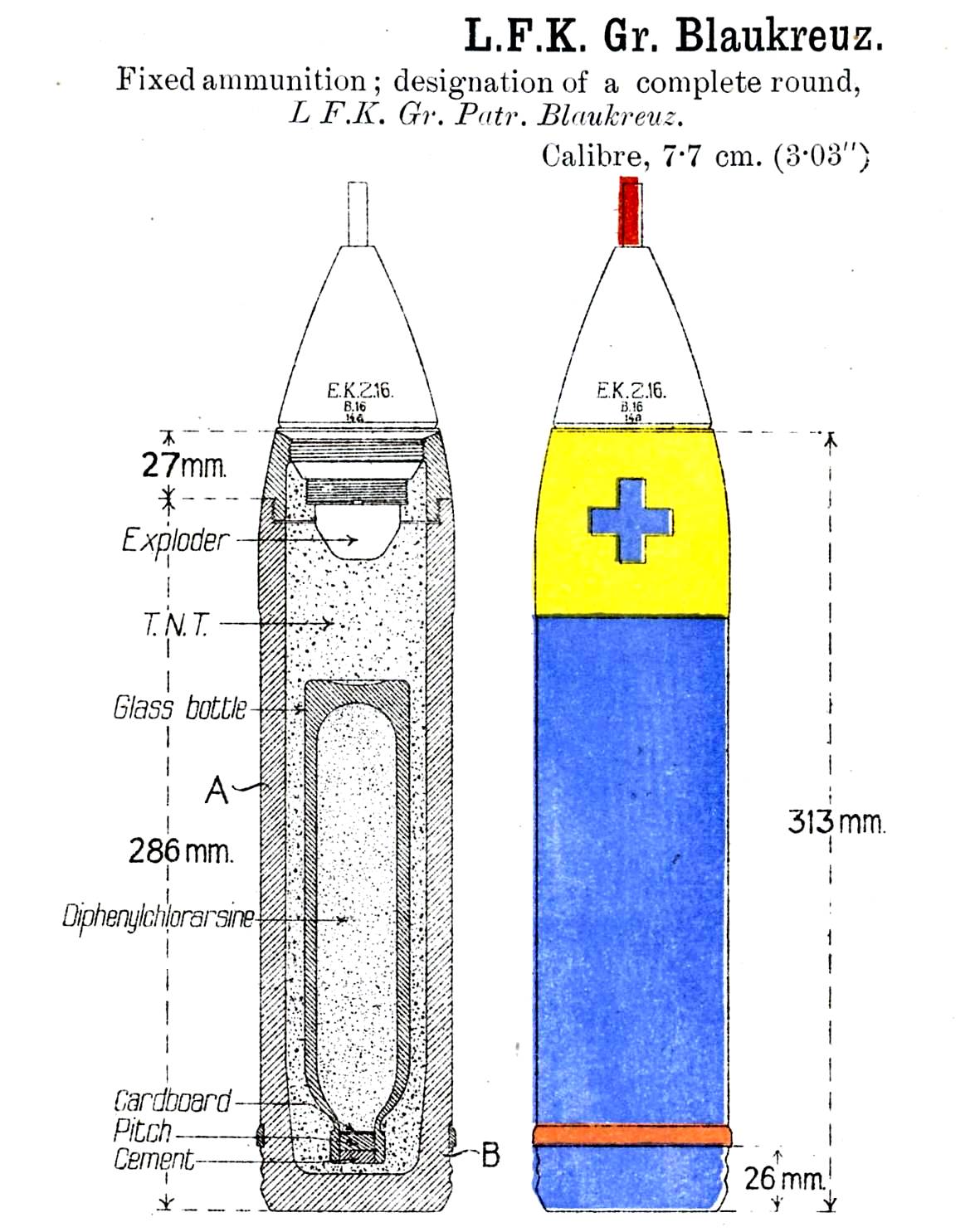

The 92nd Division began receiving German high explosive and gas artillery fire on its lines during 25 August 1918 as retaliation from a raid conducted 9 days prior (16 August 1918) by the 6th Infantry and its capture of the town of Frapelle. Amid the shelling the 92nd Division units occupying the front line were three companies of the 365th Infantry, five companies of the 366th Infantry, two companies of the 367th Infantry, three companies of the 368th Infantry, as well as other combat units placed in support and reserve of the 92nd Division.

German Army air superiority in the Saint Die Sector led to supply disruption and casualties. as any time the weather was clear enough the frontline trenches of the 366th Infantry Regiment were bombed by German planes. The German planes had also assisted in directing artillery fire for barrages that commonly lasted more than 30 minutes at a time. Subsequently, the German artillery and aerial bombings were accurate enough to bombard the railroads used by French supply trains, as well as target the 366th’s lines with shrapnel, high-explosive and gas shells.

German Army air superiority in the Saint Die Sector led to supply disruption and casualties. as any time the weather was clear enough the frontline trenches of the 366th Infantry Regiment were bombed by German planes. The German planes had also assisted in directing artillery fire for barrages that commonly lasted more than 30 minutes at a time. Subsequently, the German artillery and aerial bombings were accurate enough to bombard the railroads used by French supply trains, as well as target the 366th’s lines with shrapnel, high-explosive and gas shells.

29 August 1918:

“Except for the occasional enemy raids the short month in the sector, from 29 August to 19 September [1918], was not particularly hazardous. Artillery fire came into the area more or less on schedule, and periodic bursts of rifle and machine gun fire sometimes caught the unwary, but most dangerous, where the lines came close to one another, were the hand grenades lobbed over without warning… During those three weeks G-2 generously estimated that [German] artillery had fired a total of 22,366 shells into the sector.”

30 August 1918:

Until 30 August 1918, the French had retained command of the Saint Die Sector where the 92nd Division had been located, meanwhile the 92nd Division were trained in trench maneuvers and in patrolling the mountains. After their first full week in the Saint Die Sector, the 366th Infantry Regiment had taken complete responsibility for no-man’s-land and participated in nightly patrols over the first and second-line German trenches.

31 August 1918:

On the night of 31 August 1918, the 92nd Division experienced one of the most intense engagements of its time in France when German forces attacked Frapelle in an attempt to retake the village. The attacking German infantry had been supported by intense German artillery with mustard gas. It was during this skirmish that the 92nd Division had been exposed to the German Model 41 Wechselapparat’s (flame-throwers) for the first time.

The 92nd Division successfully repulsed the German attack and caused heavy German casualties during its defense of Frapelle. Meanwhile the 92nd Division sustained 34 wounded and gas with 4 Killed In Action including its first officer killed, First Lieutenant Thomas Bullock of the 367th Infantry Regiment.

1 September 1918:

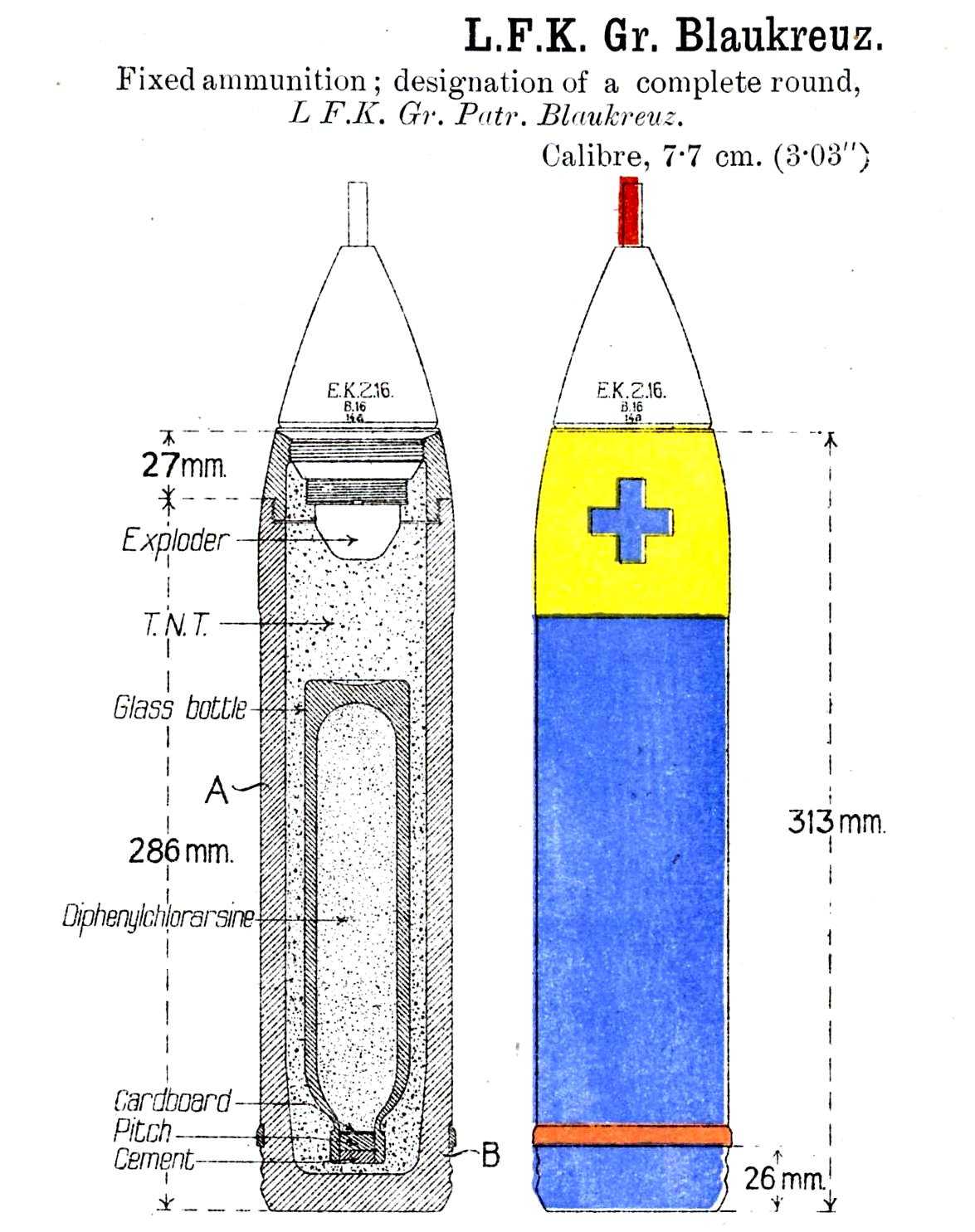

By 1 September 1918, the 92nd Division had taken control of their line in the Saint Die Salient. To test the fortitude of these new and inexperienced defenders, small German units supported by heavy artillery, aerial support, sneeze gas and tear gas made a series of raids that lasted until 4 September 1918. During the opening of the raids, German artillery bombarded the 92nd Division with more than 12,000 shells; despite their efforts, however, the Germans were unable to break the 92nd from their position. During this three day defense, the 92nd Division sustained 92 casualties: 8 Killed In Action, 39 wounded, and 45 gassed.

Around 1230 hours (12:30 P.M.) and 1500 hours (3:00 P.M.), the Germans attacked the lines of the 365th and 366th Infantry Regiments located at Ormont. The Germans began their attack with heavy artillery barrages and more than 12,000 shells fired on the frontlines. Regardless of the German attempts, the 365th and 366th Infantry Regiments proved their defensive abilities by successfully repelled the German attacks.

A lesson learned during these attacks were that the Small Box Respirators (SBR) issued to the 92nd Division were ineffective due to improper training they received before their assignment to this sector. The SBR’s were also ill-fitting and the eyepieces were often worn-out, subsequently the 92nd Division Gas Officer had reported that at least 1,500 men could not be properly fitted and were not safely protected from the German gas.

A lesson learned during these attacks were that the Small Box Respirators (SBR) issued to the 92nd Division were ineffective due to improper training they received before their assignment to this sector. The SBR’s were also ill-fitting and the eyepieces were often worn-out, subsequently the 92nd Division Gas Officer had reported that at least 1,500 men could not be properly fitted and were not safely protected from the German gas.

Numerous patrols were sent out from the 92nd Division’s lines, upon returning there were no reports of contact with German units. In many cases, German trenches were found abandoned and it was believed that the Germans were anticipating a fight in a general or large-scale engagement.

2 September 1918:

A German gas attack on soldiers during World War One. Dated 1914. (Universal History Archive/UIG via Getty Images) – Colourized

During a German shelling on the 92nd Division’s lines, an officer and eight men of the 92nd Division had failed to recognize the odor of mustard gas mix due to the smell of the High Explosive shells bursting around them, and had become gas casualties as a result.

4 September 1918:

The Germans opposing the 92nd Division line launched another raid against the frontlines, after a brisk firefight the elements of the 92nd Division managed to drive off the German raids.

7 September 1918:

During the night of 7 September and into the early morning of 8 September 1918, another German gas attack hit the 92nd Division’s lines with a reported 730 gas shells falling on the trenches. This was the first and only time the German raiding parties were successful in entering the trenches of the 366th Infantry Regiment’s lines, however, after a brisk firefight the Germans determined that the 366th would not be driven from their positions.

8 September 1918:

The conclusion was made by the Germans that the 92nd Division would not easily be driven off, and resulted in using ranged attacks to harass the 366th Infantry Regiment including the use of snipers, light artillery mounted on armored trucks, machine-guns and heavy artillery, which often targeted the 92nd Division’s strongpoints. These German motor trucks were extremely effective against the 92nd Division patrols in no-man’s land during the early part of September.

11 September 1918:

On 11 September 1918, a recognition was given to the 366th Infantry Regiment as having more superior arms than the Prussians it had been facing, and it was thoroughly believed that it had the means to advance and capture the villages of Beulay and Provenchires. In capturing these towns, the 92nd Division would create a advantageous position whereby fewer casualties would be sustained due to remaining in the valley of Fave. However, despite this belief an advance never took place on the towns.

12 September 1918:

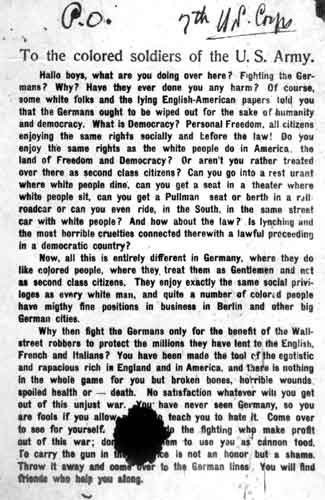

During an early morning patrol two members of a patrol party from the 92nd Division were captured by the Germans. Through this capture, the Germans had learned that the 92nd Division was made-up of African American troops. The Germans attempted to use this to their advantage by changing their tactics from artillery barrages and gas attacks, to propaganda for the 92nd to change sides.

During the morning of 12 September 1918, a section of the 367th Infantry Regiment was bombarded with fliers instead of gas shells. The circular letters were addressed to the troops of the 367th Infantry Regiment stating:

“TO THE COLORED SOLDIERS OF THE U.S. ARMY

“TO THE COLORED SOLDIERS OF THE U.S. ARMY

Hello, boys, what are you doing over here? Fighting the Germans? Why? Have they ever done you any harm? Of course some white folks and the lying English-American papers told you that the Germans ought to be wiped out for the sake of Humanity and Democracy.

What is Democracy? Personal freedom, all citizens enjoying the same rights socially and before the law. Do you enjoy the same rights as white people do in America, the land of Freedom and Democracy, or are you rather not treated over there as second-class citizens? Can you go into a restaurant where white people dine? Can you get a seat in the theater where white people sit? Can you get a seat or a berth in the railroad car, or can you even ride, in the South, in the same street car with white people? And how about the law? Is lynching and the most horrible crimes connected therewith a lawful proceeding in a democratic country?

Why, then, fight the Germans only for the benefit of the Wall street robbers and to protect the millions they have loaned to the British, French, and Italians? You have been made the tool of the egotistic and rapacious rich in England and in America, and there is nothing in the whole game for you but broken bones, horrible wounds, spoiled health, or death. No satisfaction whatever will you get out of this unjust war.

You have never seen Germany. So you are fools if you allow people to make you hate us. Come over and see for yourself. Let those do the fighting who make the profit out of this war. Don’t allow them to use you as cannon fodder. To carry a gun in this war is not an honor, but a shame. Throw it away and come over into the German lines. You will find friends who will help you along.”

Regardless of their efforts the German propaganda had no effect on the dedicated troops of the 92nd Division.

Regardless of their efforts the German propaganda had no effect on the dedicated troops of the 92nd Division.

14 September 1918:

On 14 September 1918, only two days after the propaganda reached the troops of the 367th Infantry Regiment, the 92nd Division had captured their first Prisoners of War (POW) when a raiding party of the 366th Infantry Regiment surprised and captured a group of five soldiers. Previous raiding parties had managed to capture rifles, machine-guns and message dogs; but had not managed to capture any POW’s prior to this day.

15 September 1918:

In retaliation to the capture of the Algerian troops, German aerial activity increased and at 1400 hours (2:00 P.M.) on 15 September 1918 a German Fokker combat plane flew above the 92nd Division lines at an altitude of 8,000 feet and began strafing and bombing the lines. At 1420 hours (2:20 P.M.) minutes later, a French plane flown by French Lieutenant Fagon spotted the German Fokker and the two planes began a dog fight above the 92nd Division lines. After approximately 20-minutes of fighting, Lieutenant Fagon successfully shot and killed the German pilot.

18 September 1918:

On 18 September 1918, elements of the American 81st “Wildcat” Division (attached to the French 20th Division) began relieving the 92nd Division. The 368th Infantry Regiment continued to hold its lines in the subsector Ravines in the Saint Die District.

19 September 1918:

During the night the 1st Battalion of the 368th Infantry was relieved from the Center of Resistance (C.R.) Colxns by a battalion of a French Regiment. The 2nd Battalion, 368th Infantry was relieved from the C.R. Coirots by three companies of the French 20th Division, French XXXIII Corps and 1 company of the American 321st Infantry Regiment, 81st Division. The 3rd Battalion, 368th Infantry was relieved from the C.R. Colxns by a battalion of a French Regiment and were to rendezvous at Rage l’Stape.

The 2nd Battalion, 368th Infantry was to rendezvous at Stival and embussed at 2030 hours (8:30 P.M.) at Pajails, where it went to Vanemont and La Cote. The 3rd Battalion, 368th Infantry embussed at the same time in La Haute-Nouviville to go to Concizuk.

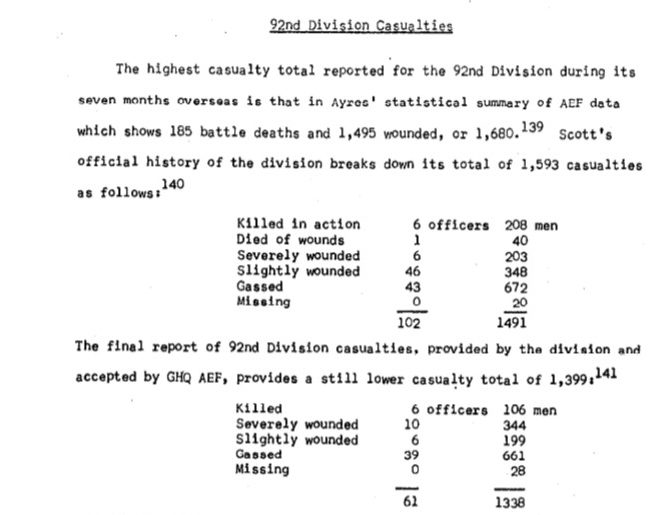

A casualty report from the 92nd Division’s G-3 reported 24 Killed In Action (KIA), 108 Wounded, 49 Gassed, and 5 Missing In Action (MIA). In addition, 12 soldiers were accidently killed and another 31 wounded due to careless weapons handling.

20 September 1918:

At 1000 hours (10:00 A.M.), the command of the sub-sector previously controlled by the 92nd Division had passed to Colonel Louis-Gaston Zapff of the French 116th Infantry Regiment. Around the same time, the 2nd Battalion, 368th Infantry Regiment arrived at Varimont and La Cote where it entrained at the Corcikol entraining area to go to Givry-en-Argonne.

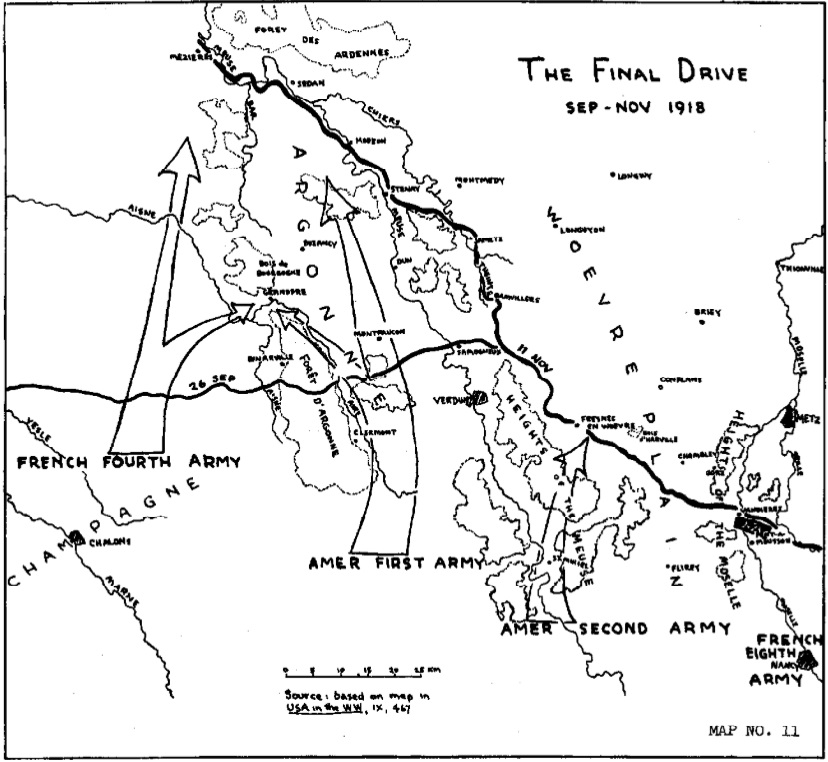

With the American 81st “Wildcat” Division, along with a French unit, taking over the Saint Die Sector where the 92nd Division had been located, the 92nd Division was officially relieved of duty in the Saint Die Sector and had began departing by road and rail to the Argonne. While en-route to the Meuse-Argonne, General Hunter Liggett (commander of the American First Army, I Corps) issued orders for one regiment of the 92nd Division to report for temporary duty with the French XXXVIII Corps.

With the American 81st “Wildcat” Division, along with a French unit, taking over the Saint Die Sector where the 92nd Division had been located, the 92nd Division was officially relieved of duty in the Saint Die Sector and had began departing by road and rail to the Argonne. While en-route to the Meuse-Argonne, General Hunter Liggett (commander of the American First Army, I Corps) issued orders for one regiment of the 92nd Division to report for temporary duty with the French XXXVIII Corps.

Liggett and other commanders had identified a problem in the upcoming Meuse-Argonne Offensive in which a gap would develop between the French Fourth Army and American First Army. The plan for the regiment chosen from the 92nd Division was to provide liaison and protection within this gap, the group would ultimately be composed of the French 11th Cuirassiers and the American 368th Infantry Regiment, known as Groupement Durand.

The relief of the 92nd Division was concluded on 20 September 1918 and the 92nd Division departed for the Argonne.

21 September 1918:

On 21 September 1918 the 92nd Division left the Saint Die Sector and relocated in the Corcieux zone for entrainment. Orders directed the 92nd Division to proceed to the Department of the Meuse and take positions as the corps reserve for the American I Corps. At 0500 hours (5:00 A.M.) the 1st Battalion, Headquarters Company, Machine-Gun Company, and a portion of the supply company of the 368th Infantry Regiment physically entrained at Corcieux to travel to Givry-en-Argonne. From Corcieux and other nearby entraining points, units of the 92nd Division (excluding the 167th Field Artillery Brigade and the 317th Ammunition Train) entrained en-route to the Argonne region.

Meanwhile, the 366th Infantry Regiment marched 20 kilometers with heavy packs to entrain with other units of the 92nd Division, and then were quickly rushed to the village of Le Chemin. However, the officers of the 366th were disappointed in thinking that their opportunity for the regiment to prove itself would never be fully realized. Although German raiding parties were often driven off by the 366th, even without the assistance of French sector artillery, the 366th was never given an opportunity that allowed them to advance their line.

Preparations for the largest American military operation in history, the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, were nearly complete.

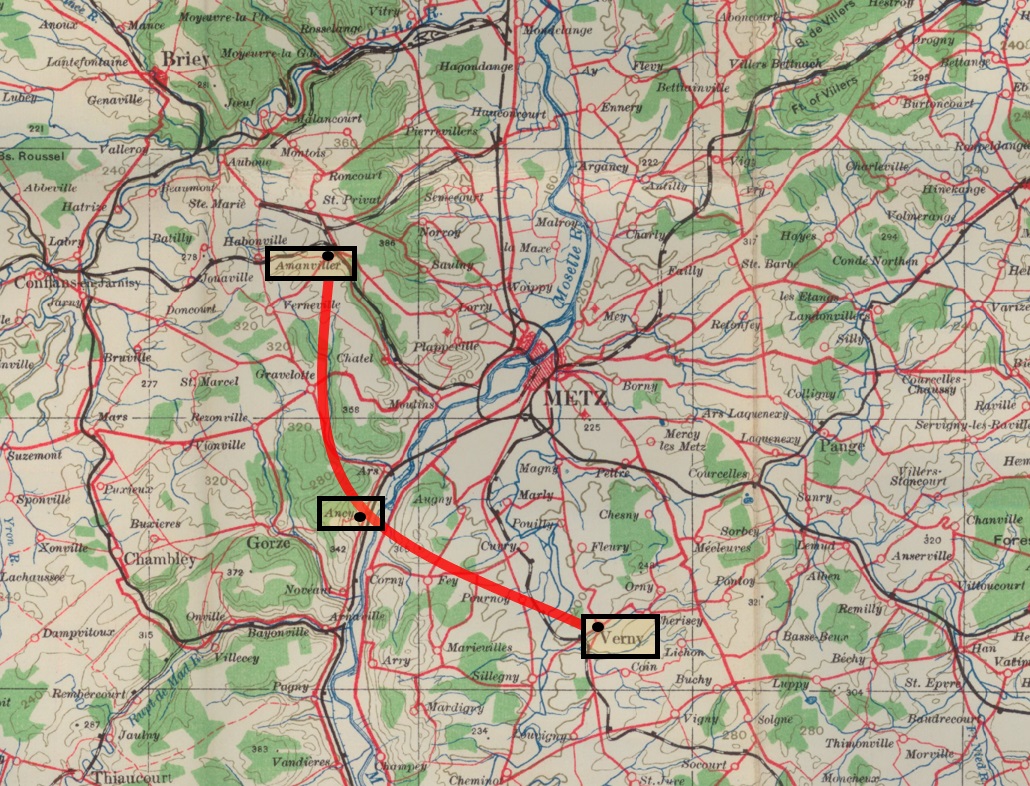

92nd Division - The Meuse-Argonne Offensive

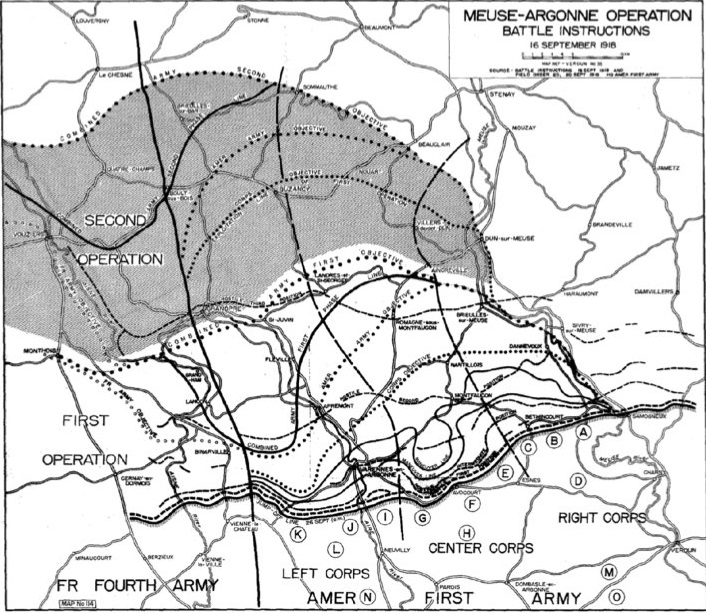

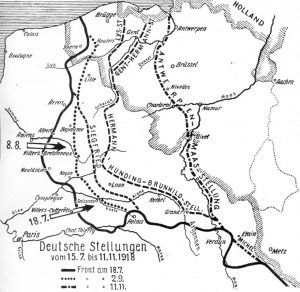

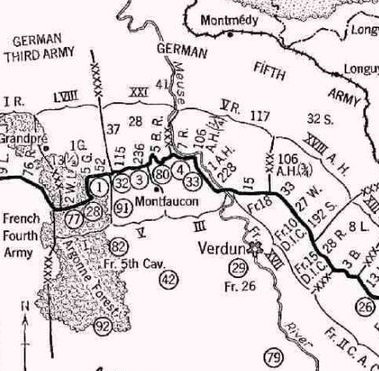

The Meuse-Argonne Offensive (26 September to 11 November 1918) was the largest American military operation in history, and had involved more than 1.2 million American servicemembers. The 92nd Division (excluding the 368th Infantry Regiment and the 167th Field Artillery Brigade) was placed in reserve of the American I Corps, American First Army at the beginning of the offensive, whereby the American First Army was to be directed against principal German lateral line of supply known as the Carignan-Sedan-Meziers railroad (located about 53 kilometers from the front of Sedan). Severing this German line of supply would render the German positions to the West and Northwest of Sedan untenable.

To protect the line of supply, the Germans had constructed a series of fortifications since 1914 and four distinct defensive positions:

The First defensive position laid close behind the frontline.

The Second defensive position included Montfaucon and traversed the Argonne (south of Apremont)

The Third defensive position was known as the Kriemhilde Stellung which ran from the vicinity of Metz to the North Sea. This position had also extended from Bois de Foret, across the heights of Cunel and Romagne, included the high ground north of Grand Pre, and had formed a portion of the Hindenburg Line.

The Fourth defensive position included the heights of Barricourt extending west to Buzancy and Thenorgues.

The first three defensive positions were thoroughly organized and had numerous intermediate defensive positions constructed between them. The defensive positions were also naturally fortified by the difficult terrain any attacking force would have to overcome.

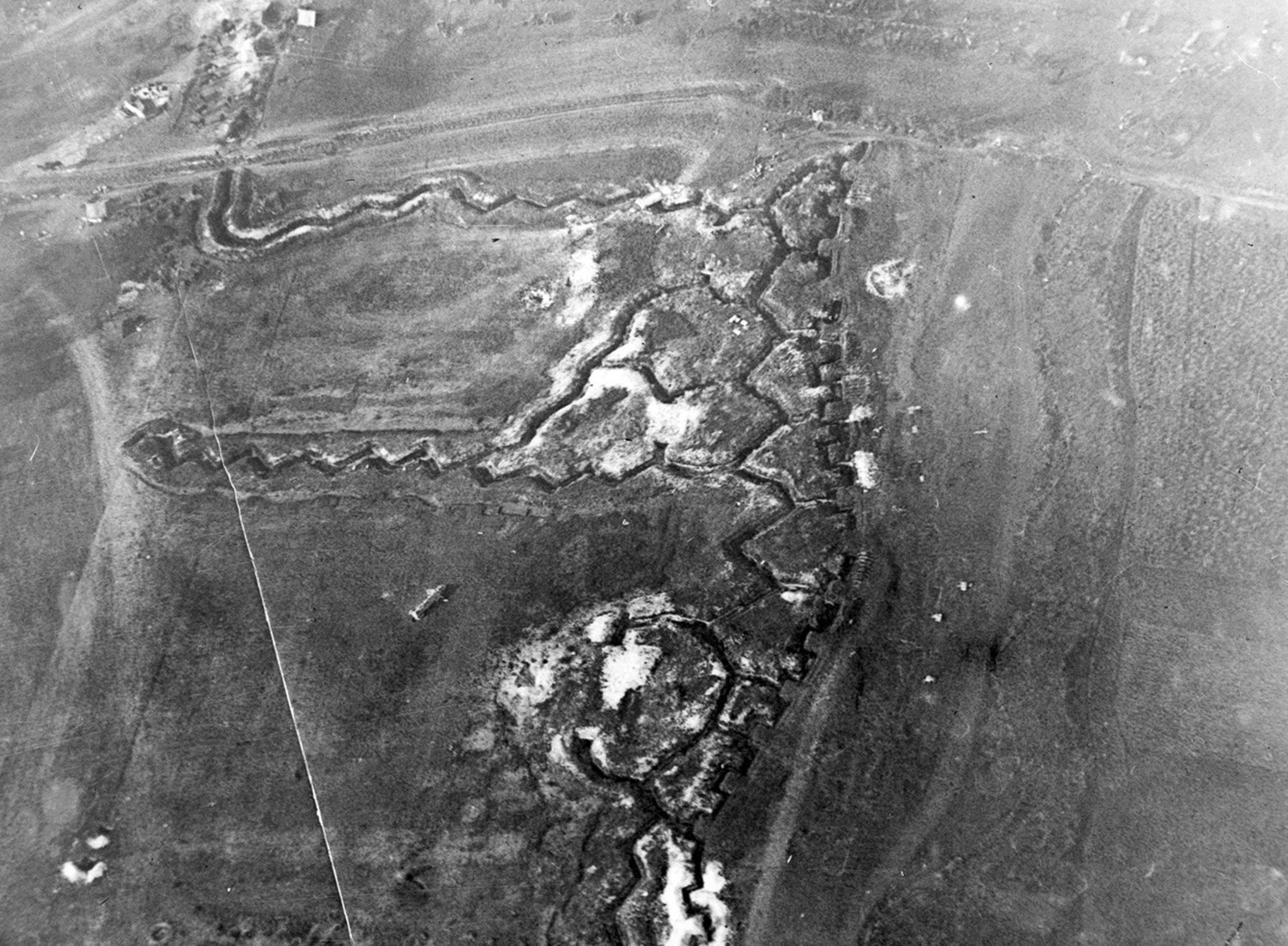

This photograph of Kriemhilde Stellung – the position of a German Defensive line during the Meuse Argonne Offensive

The 92nd departed from the Saint Die Sector and were under orders to take positions as Corps Reserve, the division traveled more than 300 miles during its journey from Saint Die Sector to the Argonne. By the afternoon of 23 September 1918, the 92nd Division arrived at their destination of Le Chemin in the Department of the Meuse at 1900 hours (7:00 P.M.) under very heavy rain. Almost immediately, the men of the 92nd Division began an arduous march toward the Argonne Forest and the road from Le Chemin to Camp D’Italien was riddled with dead horses, mules, and broken equipment.

The plan for the American First Army was to penetrate the Kriemhilde Stellung to force the Germans to retreat from the Argonne Forest and ensure a junction between the French Fourth Army to the left, and the American First Army on the right. For this plan to succeed, the American 77th “Statue of Liberty” Division of the American First Army would need to maintain liaison with the French 1st Dismounted Cavalry of the French Fourth Army.

Subsequently, a small liaison group known as Groupement Durand would be formed and consisted of troops from the 368th Infantry Regiment (92nd Division) and the French 11th Cuirassiers. Groupement Durand would be under the command of the French Fourth Army during its operations in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive.

Subsequently, a small liaison group known as Groupement Durand would be formed and consisted of troops from the 368th Infantry Regiment (92nd Division) and the French 11th Cuirassiers. Groupement Durand would be under the command of the French Fourth Army during its operations in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive.

22 September 1918:

At 0130 hours (1:30 A.M.), the 1st Battalion of the 368th Infantry Regiment, as well as the remainder of the Supply Company (detached from the 325th Field Signal Battalion) entrained at Corcieux for Givry-en-Argonne.

23 September 1918:

By the afternoon of 23 September 1918, the 92nd Division had arrived at their destination, whereby more than 300 miles were covered during the 92nd Divisions travels in troops trains. The 92nd detrained at the village of Le Chemin and the 92nd Headquarters were established at Saint Menehould.

At 1900 hours (7:00 P.M.), the 92nd Division began their movements toward the Argonne Forest under heavy rain. The march was difficult and exhausting to the men, mules, and horses of the division. Most of the men of 1st and 3rd Battalion, 366th Infantry hadn’t removed their shoes in more than 10 days, making the march even more strenuous on their blistered and exhausted feet. However, there was good news to help lift the spirits of the 366th. The 2nd Battalion, having been in the frontline trenches for 20 days under artillery fire, found out that 18 Distinguished Service Crosses were being awarded to men of their battalion.

At 1900 hours (7:00 P.M.), the 92nd Division began their movements toward the Argonne Forest under heavy rain. The march was difficult and exhausting to the men, mules, and horses of the division. Most of the men of 1st and 3rd Battalion, 366th Infantry hadn’t removed their shoes in more than 10 days, making the march even more strenuous on their blistered and exhausted feet. However, there was good news to help lift the spirits of the 366th. The 2nd Battalion, having been in the frontline trenches for 20 days under artillery fire, found out that 18 Distinguished Service Crosses were being awarded to men of their battalion.

Meanwhile, the 1st Battalion of the 368th Infantry, as well as a portion of the supply company from the 325th Field Signal Battalion, arrived at Givry-en-Argonne and immediately marched to La Neuville, then Bouronville. At 2030 hours (8:30 P.M.), the entire 368th Infantry marched from Bouronville, France to Camp Sounait.

24 September 1918:

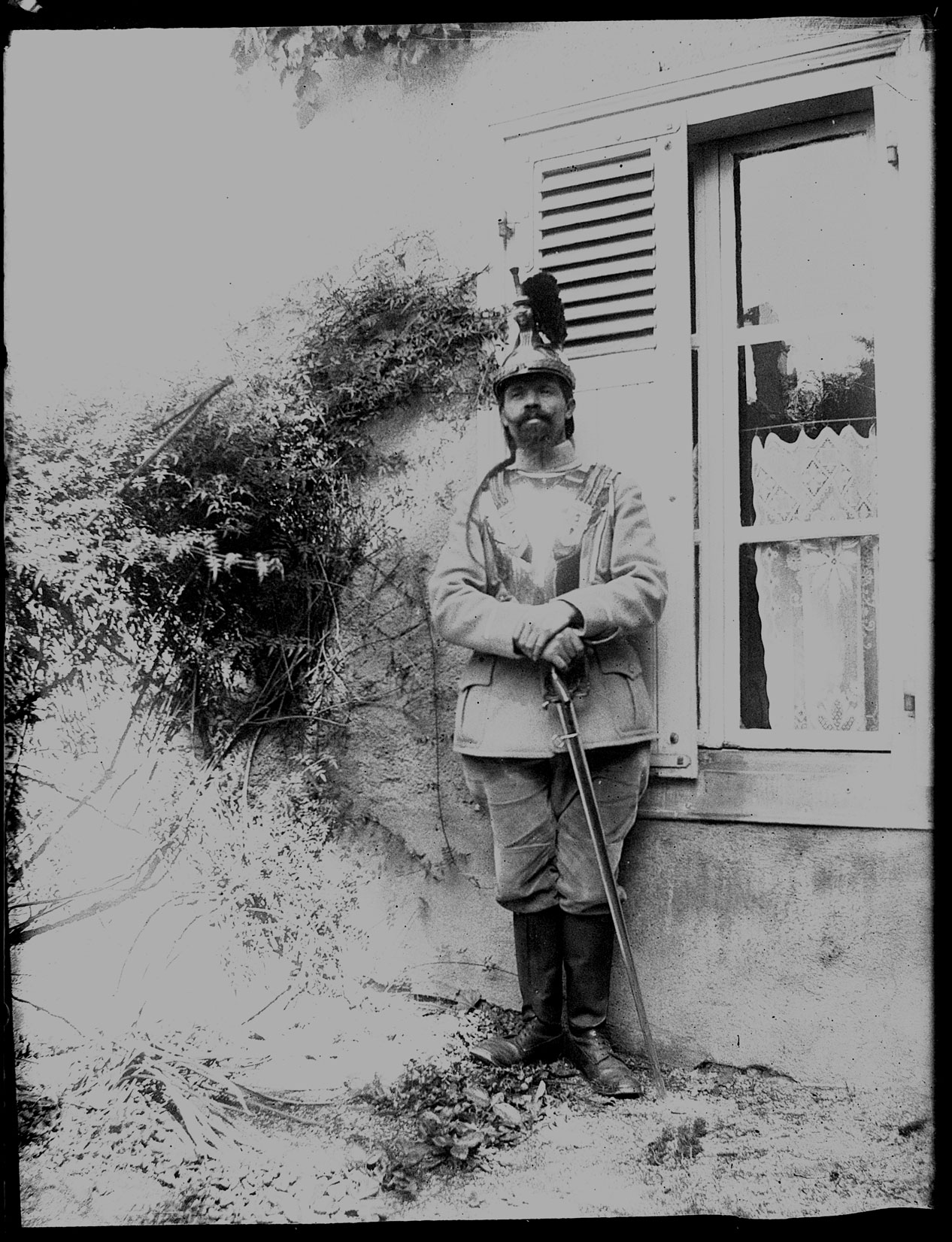

A French Cuirassier wears a bleu horizon uniform with his armor plate and helmet without protecting cloth.

Early in the morning of 24 September 1918, at 0500 hours (5:00 A.M.), the 368th Infantry Regiment completed its all-night march and arrived to the outskirts of the Argonne Forest to join the French 11th Cuirassiers.

At 0900 hours (9:00 A.M.), the 368th Infantry arrived at Camp Sounait and reported to the French 1st D.C.P. (Division de Cavalierie a Pied – Dismounted Cavalry Division) in accordance to instructions from the American First Army Corps Headquarters. Subsequently, the command of the 368th Infantry was passed to the French Fourth Army and assigned to the Brigade commanded by Colonel Rene Durand (of which Groupement Durand was named after).

At 0900 hours (9:00 A.M.), the 368th Infantry arrived at Camp Sounait and reported to the French 1st D.C.P. (Division de Cavalierie a Pied – Dismounted Cavalry Division) in accordance to instructions from the American First Army Corps Headquarters. Subsequently, the command of the 368th Infantry was passed to the French Fourth Army and assigned to the Brigade commanded by Colonel Rene Durand (of which Groupement Durand was named after).

With only four hours of rest since arriving in the outskirts of the Argonne Forest the 368th Infantry Regiment had once again began marching, this time to join the French XXXVIII Corps. The remainder of the 92nd Division proceeded to a region northwest of the Argonne Forest and assumed a reserve position.

Upon arrival, the 92nd Division was placed under the command of the American I Corps, American First Army and officially designated as the reserve element of the American I Corps. Much like the 368th Infantry Regiment (officially operating as part of Groupement Durand), various units of the 92nd Division were detached for special operations, such as the 317th Engineer Regiment, three battalions of infantry and two companies of the 351st Machine-Gun Battalion, and the 167th Field Artillery Brigade. Although the 167th Field Artillery Brigade was not attached to the 92nd Division at the time the 92nd had the 62nd Field Artillery Brigade (American 37th Division) attached to it.

Upon arrival, the 92nd Division was placed under the command of the American I Corps, American First Army and officially designated as the reserve element of the American I Corps. Much like the 368th Infantry Regiment (officially operating as part of Groupement Durand), various units of the 92nd Division were detached for special operations, such as the 317th Engineer Regiment, three battalions of infantry and two companies of the 351st Machine-Gun Battalion, and the 167th Field Artillery Brigade. Although the 167th Field Artillery Brigade was not attached to the 92nd Division at the time the 92nd had the 62nd Field Artillery Brigade (American 37th Division) attached to it.

Throughout the 92nd Division’s march (excluding the 368th Infantry Regiment) from Camp d’Italien to Camp Cabaud, the Verdun highway was littered with several miles of trucks, dead horses, broken equipment and as a result the road congestion was terrible. Due to several days of rain, the shell-torn roads caused some trucks to flip on their sides or even completely over, and given the priority of ammunition over everything else, infantry and ambulances were often halted to allow ammunition trucks to pass.

Throughout the 92nd Division’s march (excluding the 368th Infantry Regiment) from Camp d’Italien to Camp Cabaud, the Verdun highway was littered with several miles of trucks, dead horses, broken equipment and as a result the road congestion was terrible. Due to several days of rain, the shell-torn roads caused some trucks to flip on their sides or even completely over, and given the priority of ammunition over everything else, infantry and ambulances were often halted to allow ammunition trucks to pass.

To keep the trucks and supplies moving, orders were given for all transport vehicles to move to the left side of the road after the right side had come to a complete standstill. Vast efforts had been made to reopen the roadways, but the roads became completely blocked for as long as 7 kilometers by midnight of 24 September 1918. Trucks and troops alike were bogged down by the mire and mud, the 92nd Division was forced to move by foot in small detachments to reach the woods above Passaavant-en-Argonne the next morning.

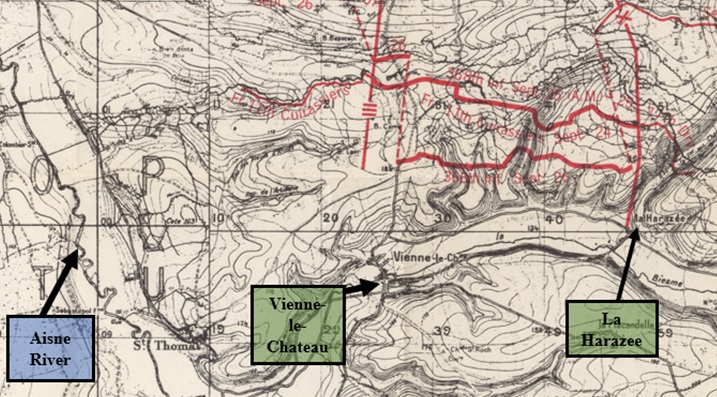

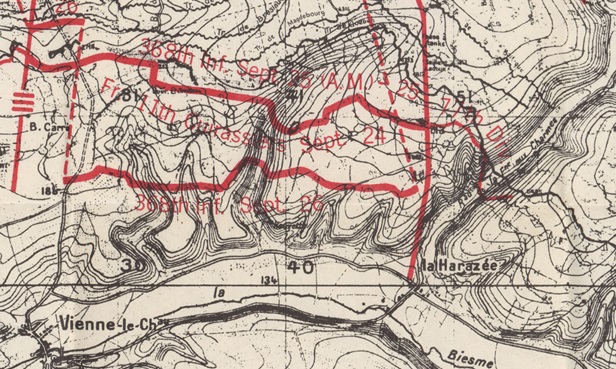

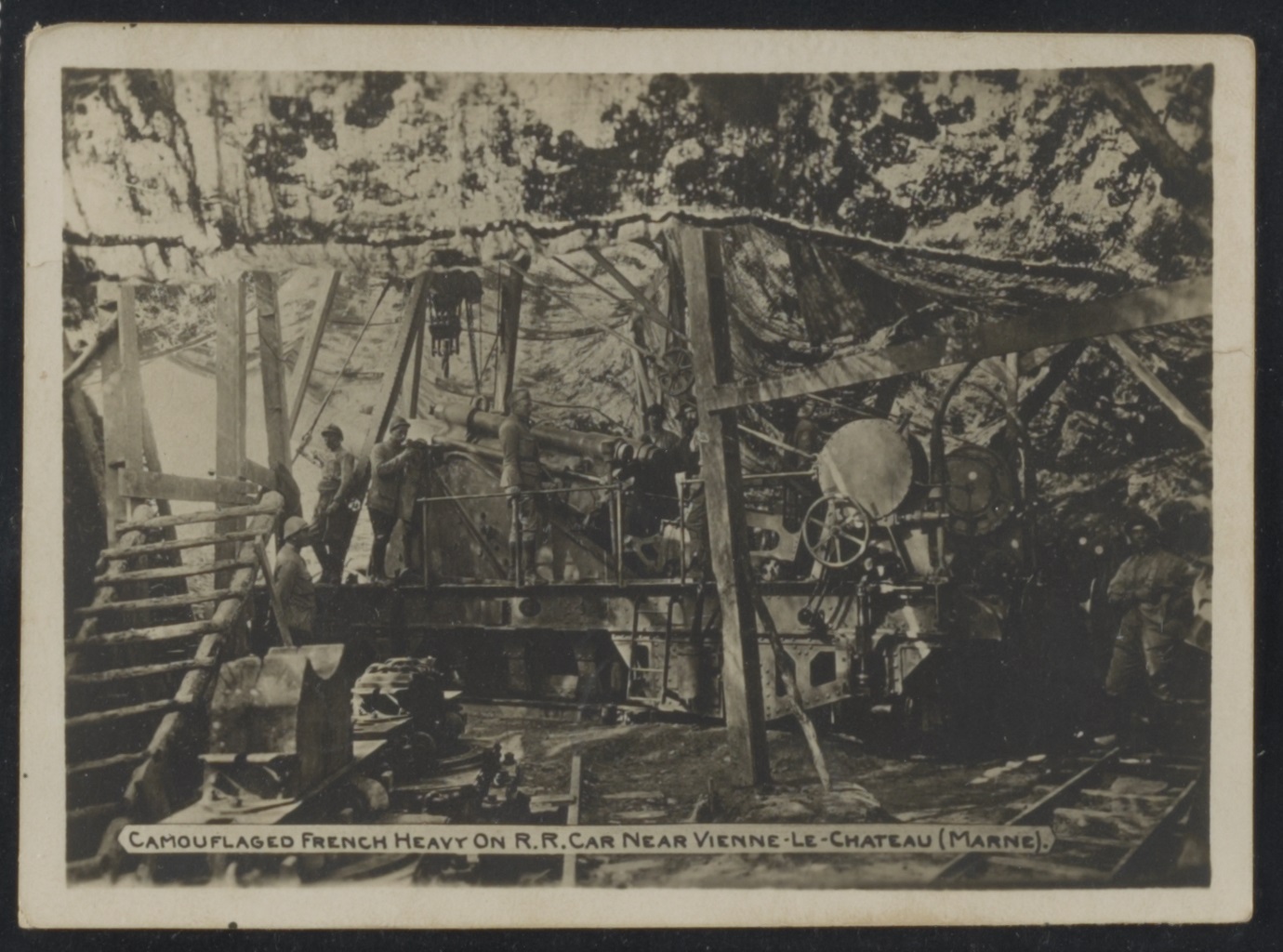

By 2100 hours (9:00 P.M.), the 368th Infantry Regiment marched to the front and was assigned to the right bank of the Aisne River, north of Vienne-le-Chateau and La Harazee. Due to the long day of marching and the muddy terrain, the 368th Infantry Regiment was physically exhausted and hungry, however this wasn’t the only troubles the 368th encountered.

By 2100 hours (9:00 P.M.), the 368th Infantry Regiment marched to the front and was assigned to the right bank of the Aisne River, north of Vienne-le-Chateau and La Harazee. Due to the long day of marching and the muddy terrain, the 368th Infantry Regiment was physically exhausted and hungry, however this wasn’t the only troubles the 368th encountered.

“The intense fatigue only compounded the lack of preparation for what lay before them. What should have ideally been weeks of careful coordination was instead reduced to several hours hastily thrown together planning. The officers lack[ed] maps and could not familiarize themselves with the terrain. The infantrymen did not have much-needed light machine-guns and grenade launchers. Most troubling, without essential supplies such as signal flares and heavy wire-cutters, a reflection of the 92nd Divisions perpetually under-equipped state.“

– A Companion to the Meuse-Argonne Campaign, Page 165-166.

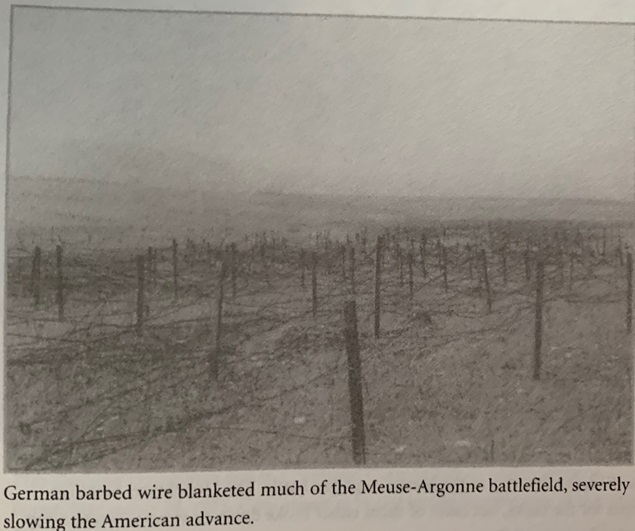

An example of the thick barbed-wire that laid across the Meuse-Argonne of which the 92nd and other divisions would have faced. The 92nd was ill-equipped and without proper equipment, including wire-cutters, to overcome obstacles such as this.

25 September 1918:

The 368th Infantry and Groupement Durand:

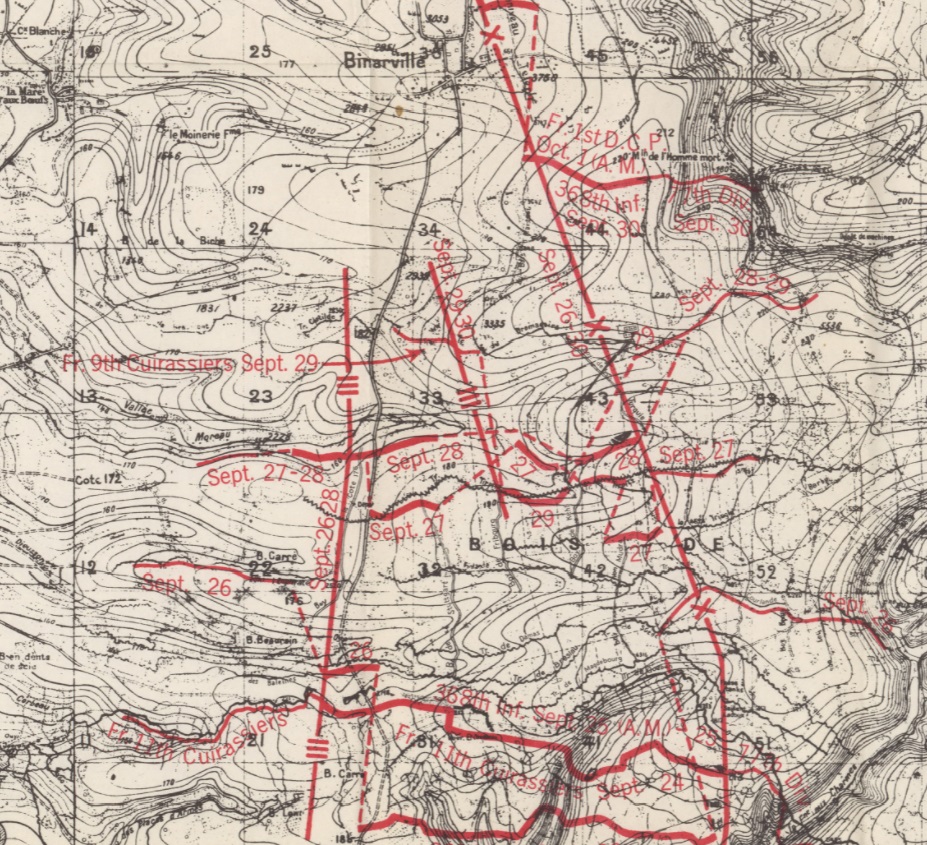

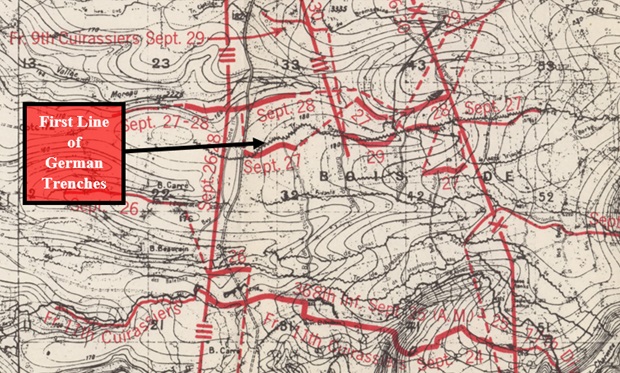

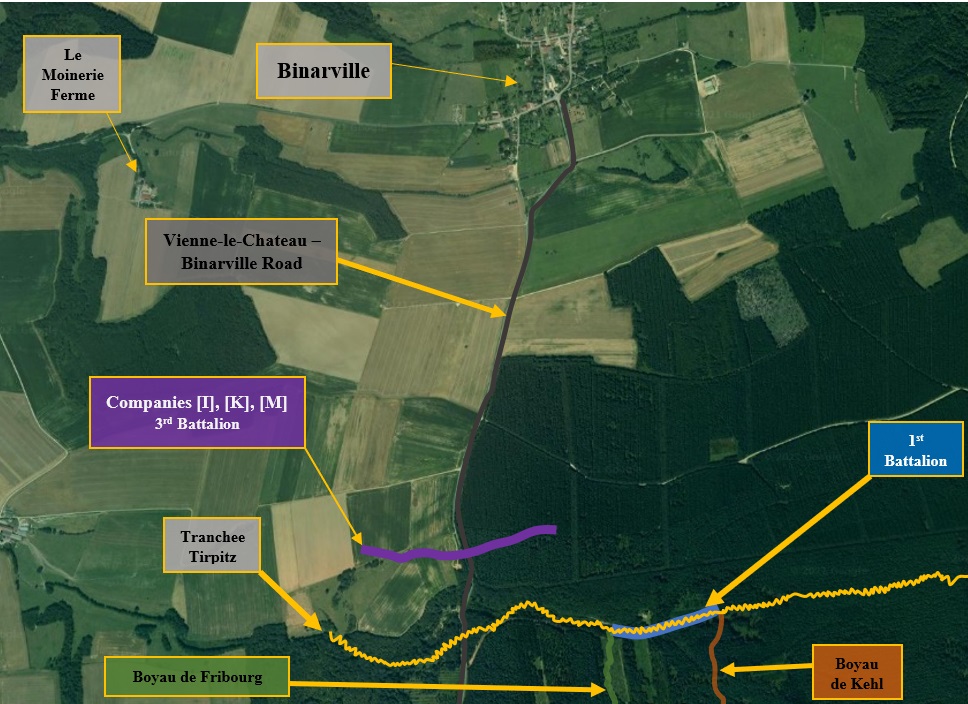

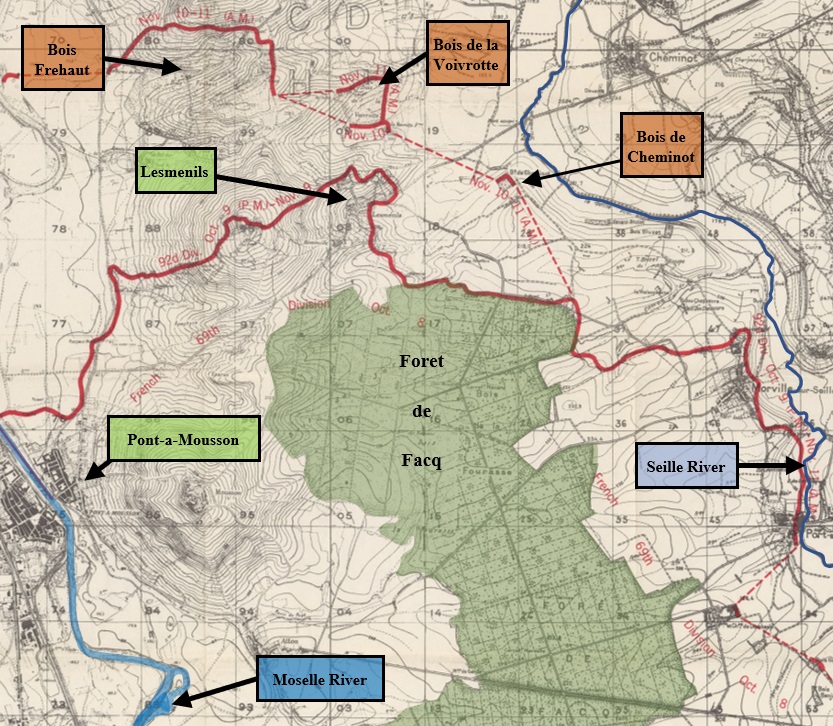

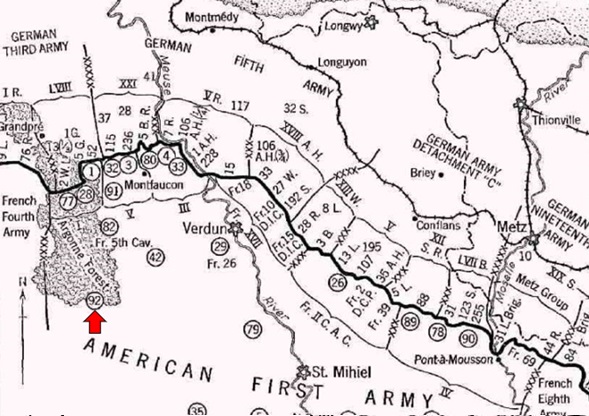

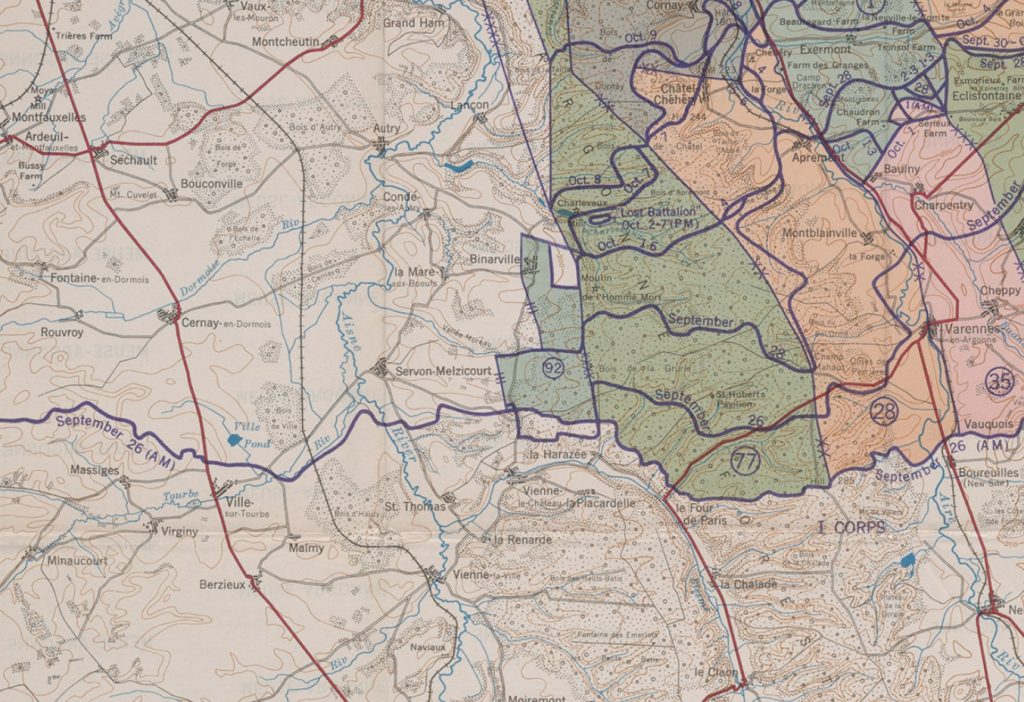

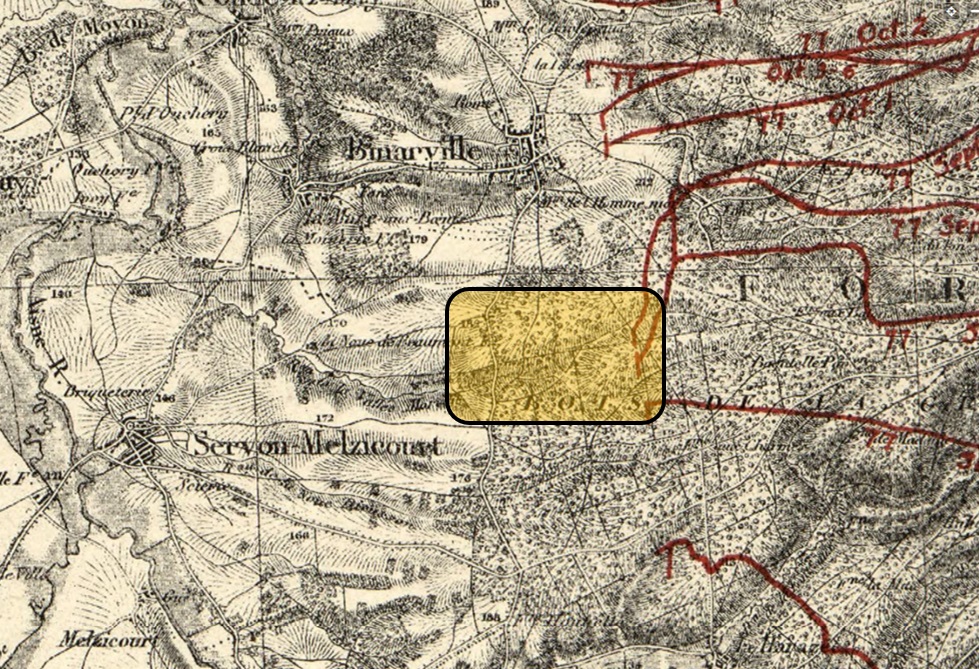

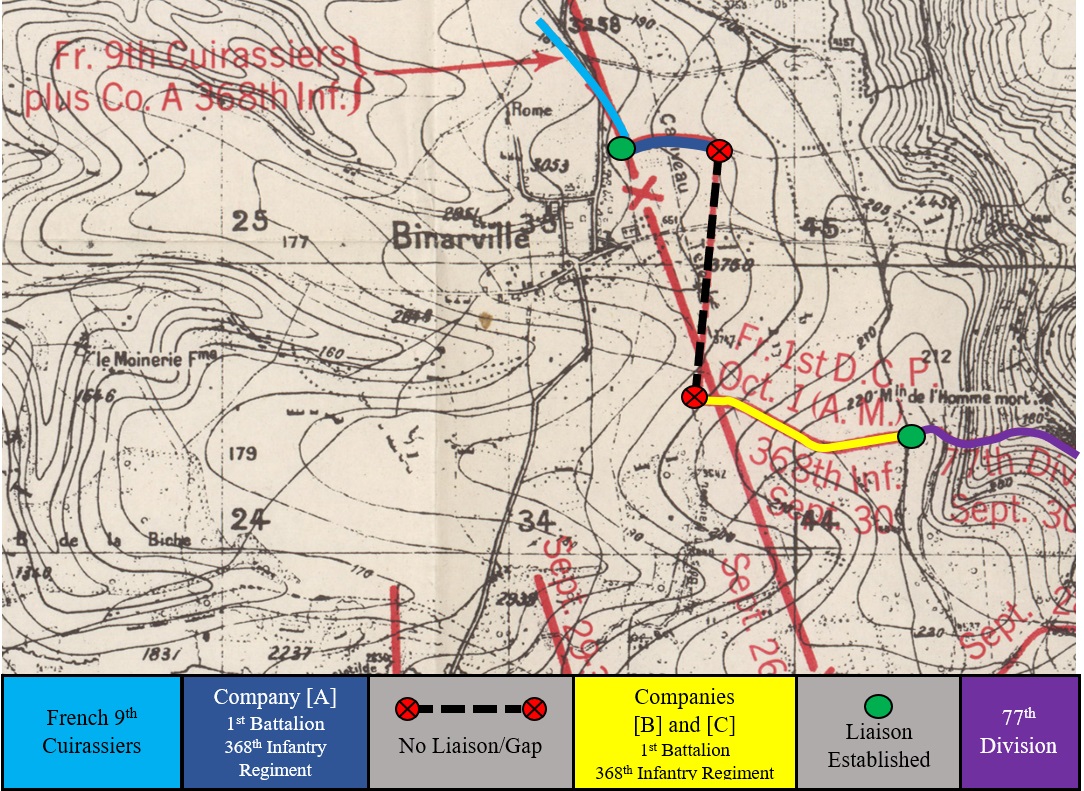

On 25 September 1918, a change in disposition of the allied troops had made it vital for the 368th Infantry Regiment and Groupement Durand to take over the sector, with the town of Binarville opposite of their frontline. Groupement Durand’s mission was to maintain contact between the French 1st Dismounted Cavalry Division of the French Fourth Army to the left, and the American 77th Division of the American First Army to the right. The sector that was held by the 368th Infantry had formed an irregular triangle that projected forward beyond the general line. In front of the 368th’s position were vast stretches of German wire entanglements that extended in intervals throughout “no-man’s land” and beyond the German wire were concealed German machine-gun emplacements. Fighting in the sector of the 368th Infantry was harder than any unit of the 92nd Division had encountered prior to that time.

This map shows the boundaries of the 368th Infantry Regiment (labeled simply as “92”) during its operations as part of Groupement Durand.

The French 1st Dismounted Cavalry Division announced that the assault troops of Groupement Durand would be in position on the night of 25 September and early morning of 26 September 1918. Special efforts were made not to attract the attention of the Germans as the American units approached their lines of departure. The 368th moved from Vienne-le-Chateau and took positions on the left flank of the American 77th Division by moving in a column of battalions, taking over a 2.5 kilometer section of front from the French 11th Cuirassiers north and south of the Biesme River.

An artillery preparation was planned to commence 6 hours prior to the attack, whereby Groupement Durand was to advance at h-hour (set for 0530 hours (5:30 A.M.)) to a line extending east and west through Servon and to occupy the first line of German trenches.

The positions obtained by Groupement Durand were to be held against all German counterattacks, which were highly anticipated and suspected to come from the Argonne Forest. While in position, the 368th were assigned to keep the Germans under surveillance and maintain contact between the French 1st Dismounted Cavalry and the American 77th Division, it as also noted that in the case of a German withdrawal the 368th were to actively pursue the Germans with the French 11th Cuirassiers.

The formation of the 368th Infantry assigned its 1st Battalion in reserve of the French 1st Dismounted Cavalry at Camp Die Haute. The 2nd Battalion was located in the front line and was to be the assault battalion with three companies along the assault front and one in reserve. The 3rd Battalion was to be in close support with three companies of the 1st Battalion on the northern bank of the Biesme River, and 1 company on the right bank.

The 368th Infantry would soon find out that they would be facing the German Third Army, which had 10 division at its disposal. The German Third Army focused its defense in the area of the Champagne and the German High Command, Oberste Herresleitung (OHL), detached an additional three divisions to serve as “intervention divisions” to assist Group Argonne when necessary.

The 368th Infantry would soon find out that they would be facing the German Third Army, which had 10 division at its disposal. The German Third Army focused its defense in the area of the Champagne and the German High Command, Oberste Herresleitung (OHL), detached an additional three divisions to serve as “intervention divisions” to assist Group Argonne when necessary.

The rest of the 92nd Division:

While the 368th was preparing to advance as part of Groupement Durand, the rest of the 92nd Division (excluding the 167th Field Artillery Brigade) arrived in the woods above Passavant-en-Argonne at 0500 hours (5:00 A.M.) on 25 September 1918. During their march to this position, although the sky was cloudy it was well lit due to the flashes of the Allied artillery cannons firing about 11 kilometers from their position. The roar of the guns was deafening and hearing or speaking to a comrade beyond a few feet was impossible.

During the morning, 8 German mustard gas shells were fired directly onto the 92nd Division and an Official Medical Department statistics indicated that between 20 August to 25 September 1918, the 92nd Division’s casualties resulted in 21 Killed In Action, 202 Wounded, and 99 Gassed. However, Field Hospital 366 didn’t record the deaths but showed 130 Wounded with 168 Gassed in the same period of time. 94 of the 168 gas cases admitted between 2 September and 5 September, alone, were due to mustard gas inhalation. However, their records changed on 8 September to state that no disease had been found, and the actual gas cases at Field Hospital 366 declined to 74.

During the morning, 8 German mustard gas shells were fired directly onto the 92nd Division and an Official Medical Department statistics indicated that between 20 August to 25 September 1918, the 92nd Division’s casualties resulted in 21 Killed In Action, 202 Wounded, and 99 Gassed. However, Field Hospital 366 didn’t record the deaths but showed 130 Wounded with 168 Gassed in the same period of time. 94 of the 168 gas cases admitted between 2 September and 5 September, alone, were due to mustard gas inhalation. However, their records changed on 8 September to state that no disease had been found, and the actual gas cases at Field Hospital 366 declined to 74.

The 92nd Division had been designated as reserve for the American I Corps, American First Army according to Secret Field Orders No. 13, Headquarters 92nd Division. The orders designated its station to be the woods north of Clermont. The woods had barely been reached when the 183rd Infantry Brigade Commander, Brigadier General Malvern H. Barnum, had ordered the 1st Battalion of the 366th Infantry to move forward and build roads across “no-man’s land.”

The 92nd Division had been designated as reserve for the American I Corps, American First Army according to Secret Field Orders No. 13, Headquarters 92nd Division. The orders designated its station to be the woods north of Clermont. The woods had barely been reached when the 183rd Infantry Brigade Commander, Brigadier General Malvern H. Barnum, had ordered the 1st Battalion of the 366th Infantry to move forward and build roads across “no-man’s land.”

The need for these roads to be quickly built were crucial due to the necessity in transporting heavy guns, ammunition, troops and supplies rapidly as the infantry attacks advanced during the offensive and contribute to its success. The advance was so rapid in the first few days of the Meuse-Argonne that the entire 183rd Infantry Brigade were all engaged in road rapid road construction. The 1st Battalion, 366th Infantry conducted its road building assignment amid German gas and high explosive shells.

26 September 1918:

“Owing to the extent of the front covered and the necessity of advancing by small groups, the battalion commanders could influence only a small part of their command….The character of the terrain and the German defense system made the advance depend entirely on the aggressiveness and leadership of the company and platoon commanders.”

–Colonel Frederick Brown, commanding officer of the 368th Infantry Regiment

The 92nd Division, excluding the 368th Infantry Regiment and the 167th Field Artillery Brigade, was placed in reserved of the American I Corps, American First Army. They were located in the woods northwest of Clermont-Beauchamp Farm, and during the opening days of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive the battalions from each of the three infantry regiments in reserve (365th, 366th, and 367th) conducted in constructing passages for supplies and ammunition across “no-man’s land.” The 368th Infantry Regiment was the only infantry regiment of the 92nd to take part in combat operations for the Meuse-Argonne Offensive.

Photo Source: Lengel, Edward G. To Conquer Hell: The Meuse-Argonne, 1918. New York: H. Holt, 2008.

Before the Meuse-Argonne Offensive began, it was noted that the 92nd Division was shorted on supplies, water and food rations. The 368th Infantry was not supplied with the necessary heavy wire cutters needed to pass through the German barbed wire, as well as hand grenades, rifle grenades, Chauchat automatic rifles, nor signal flares.

The 368th Infantry Regiment:

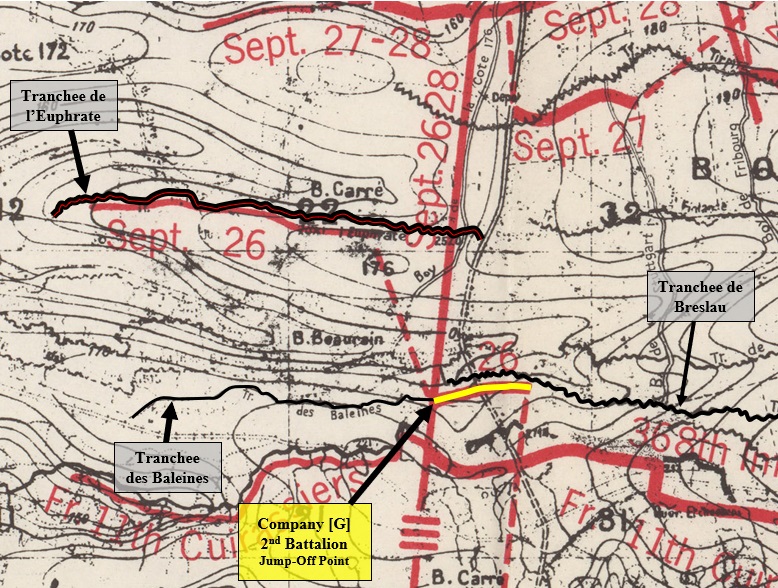

Acting as part of an element of the Franco-American Liaison Group known as Groupement Durand under the command of the French Fourth Army, the 368th Infantry and French 11th Cuirassiers were tasked with maintaining liaison between the French Fourth Army and the American First Army. On the morning of 26 September 1918, the 368th Infantry Regiment prepared to attack as the right element of Groupement Durand on and “I-Battalion” front between La Harazee to Vienne-le-Chateau.

Acting as part of an element of the Franco-American Liaison Group known as Groupement Durand under the command of the French Fourth Army, the 368th Infantry and French 11th Cuirassiers were tasked with maintaining liaison between the French Fourth Army and the American First Army. On the morning of 26 September 1918, the 368th Infantry Regiment prepared to attack as the right element of Groupement Durand on and “I-Battalion” front between La Harazee to Vienne-le-Chateau.

The 2nd Battalion was chosen as the assault battalion for the 368th Infantry and were ordered to maintain contact with the Germans, ensure liaison between the French 11th Cuirassiers and the American 305th Infantry Regiment (77th Division, American First Army), and follow any German retreat by sending out strong patrols to occupy any abandoned German position.

At 0523 hours (5:23 A.M.), the 2nd Battalion of the 368th Infantry Regiment, commanded by Major Max Elser, observed the German trench positions opposite of their line, through the dense fog that blanketed the Argonne.

At 0523 hours (5:23 A.M.), the 2nd Battalion of the 368th Infantry Regiment, commanded by Major Max Elser, observed the German trench positions opposite of their line, through the dense fog that blanketed the Argonne.

At 0525 hours (5:25 A.M.) the 2nd Battalion began their advance toward the German lines supported by the regimental machine-gun company. Almost immediately the 2nd Battalion realized that the French 1st Dismounted Cavalry Division’s artillery was inefficient in its the preparatory barrage, it had not damaged nor destroyed the thick French and German barbed-wire that had accumulated over a 4-year period and blanketed nearly 3 kilometers of “no-man’s land.”

Between the solid thicket of French and German barbed-wire that had accumulated over a 4-year period and covering nearly 3 kilometers of “no-man’s land,” and the thick underbrush that grew up through the rusted wire and created an entangled mess; the terrain was “absolutely impenetrable” according to the 368th Infantry Regiment commander, Colonel Frederick R. Brown. Overall, the 2nd Battalion encountered some of the most difficult terrain that any force of the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) had come across.

Between the solid thicket of French and German barbed-wire that had accumulated over a 4-year period and covering nearly 3 kilometers of “no-man’s land,” and the thick underbrush that grew up through the rusted wire and created an entangled mess; the terrain was “absolutely impenetrable” according to the 368th Infantry Regiment commander, Colonel Frederick R. Brown. Overall, the 2nd Battalion encountered some of the most difficult terrain that any force of the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) had come across.

Because the 368th were not supplied with heavy wire cutters, the small wire-cutters issued to the regiment proved to be useless against the massive wire defenses. The 2nd Battalion was forced to advance through existing trenches and paths, making lateral communication extremely difficult, if not, impossible. The difficult terrain and barbed-wire defenses also made the movement of the 368th Infantry’s heavy machine guns, 37mm guns, and stokes mortars nearly impractical.

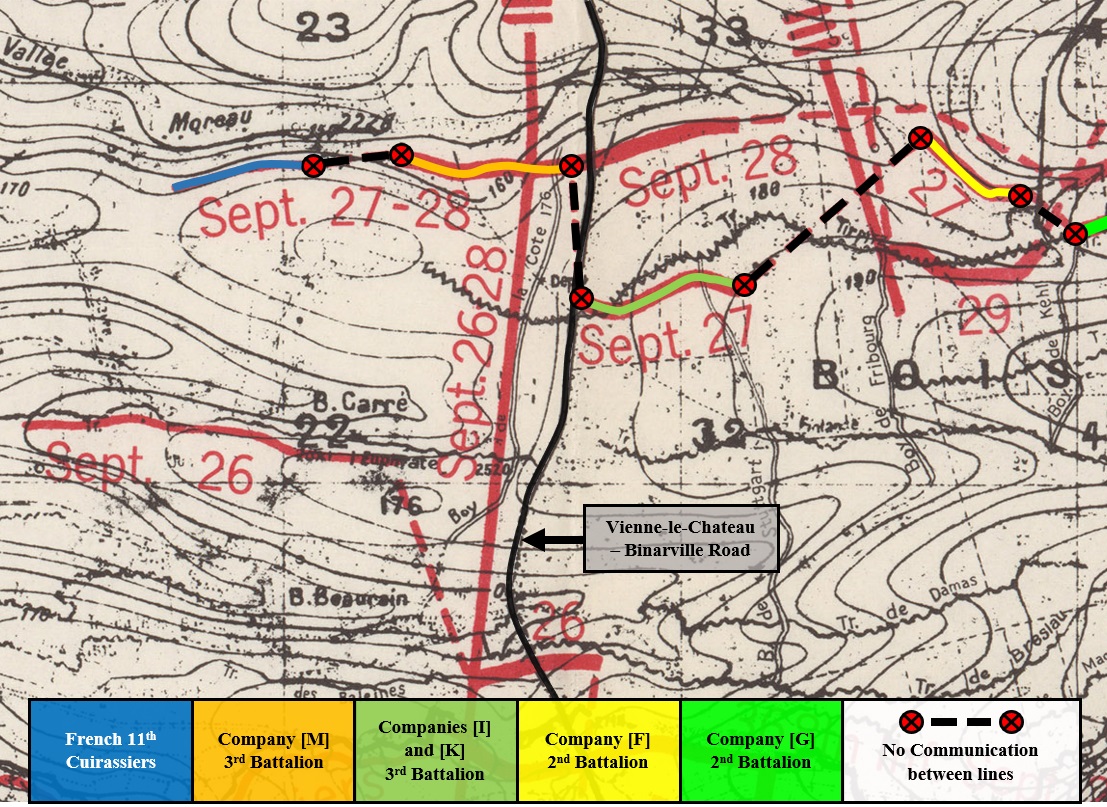

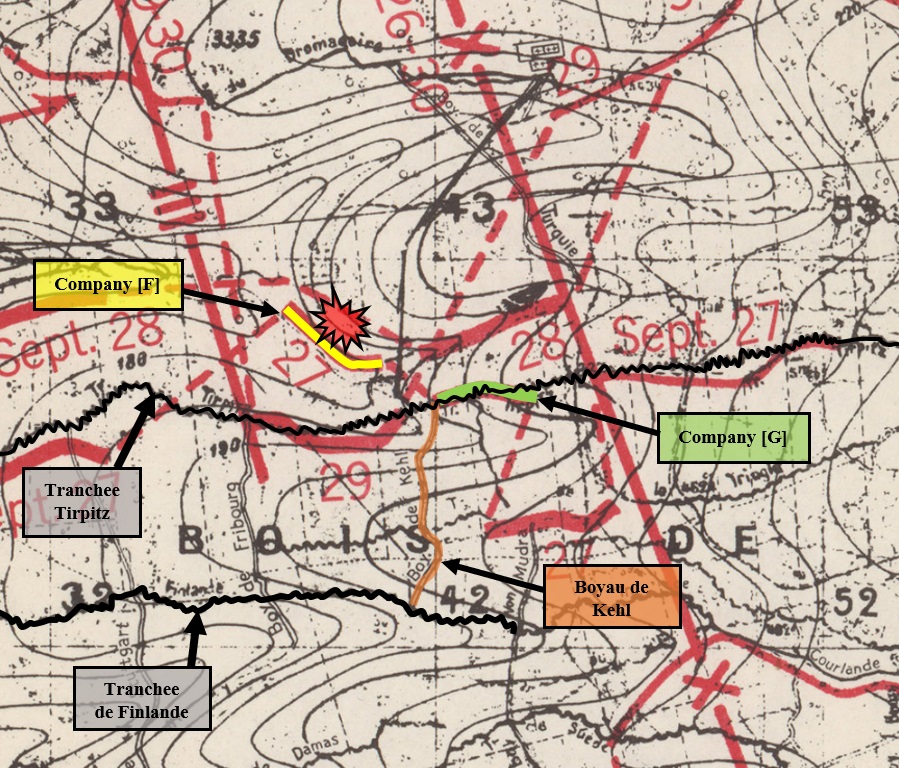

The 368th Infantry had no other option than to navigate through a maze of existing trenches that were interlaced with barbed-wire and chevaux-de-frise. The labyrinth of paths resulted in a limitation of communication between the companies of the 2nd Battalion, ultimately resulting in the separate movements and loss of contact between three groups of the 2nd battalion whereby only one group was still controlled by Major Elser. The three groups of the 2nd Battalion consisted of Company [G] to the left, Company [F] in the center, and Companies [E] and [H] to the right.

The 368th Infantry had no other option than to navigate through a maze of existing trenches that were interlaced with barbed-wire and chevaux-de-frise. The labyrinth of paths resulted in a limitation of communication between the companies of the 2nd Battalion, ultimately resulting in the separate movements and loss of contact between three groups of the 2nd battalion whereby only one group was still controlled by Major Elser. The three groups of the 2nd Battalion consisted of Company [G] to the left, Company [F] in the center, and Companies [E] and [H] to the right.

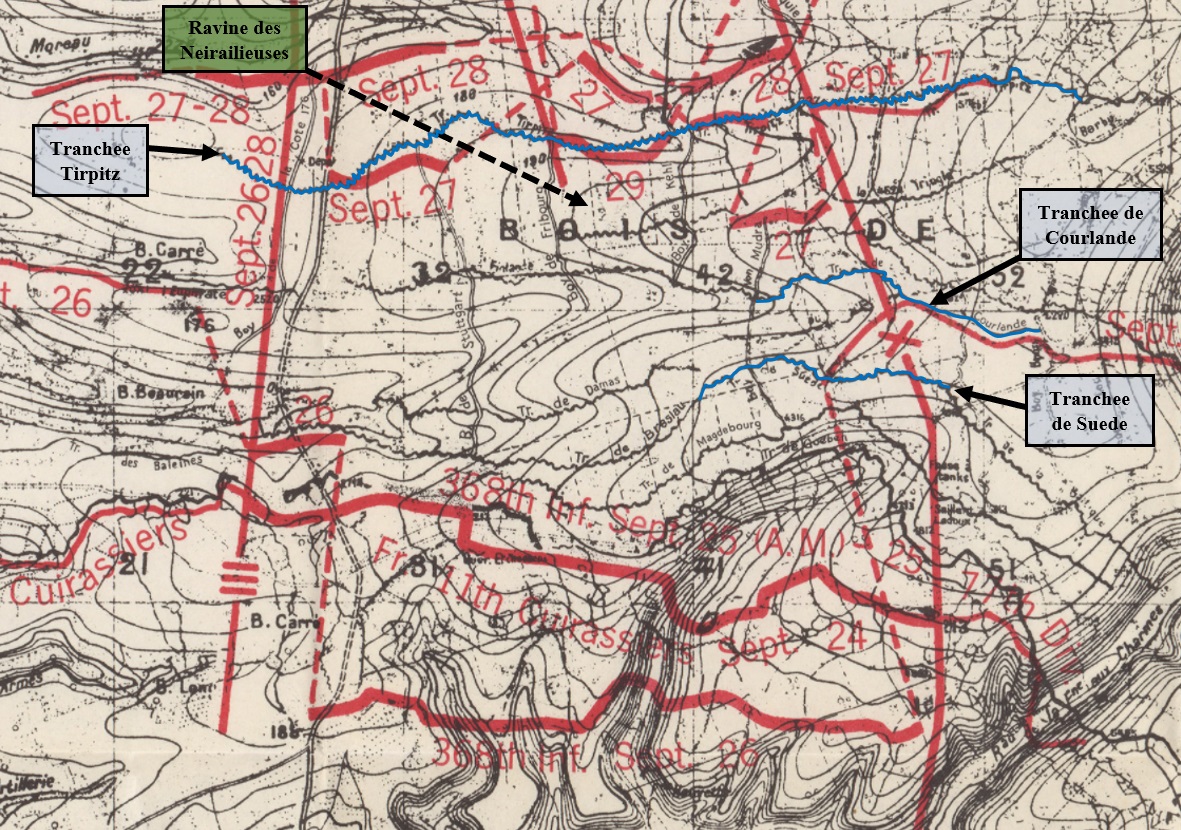

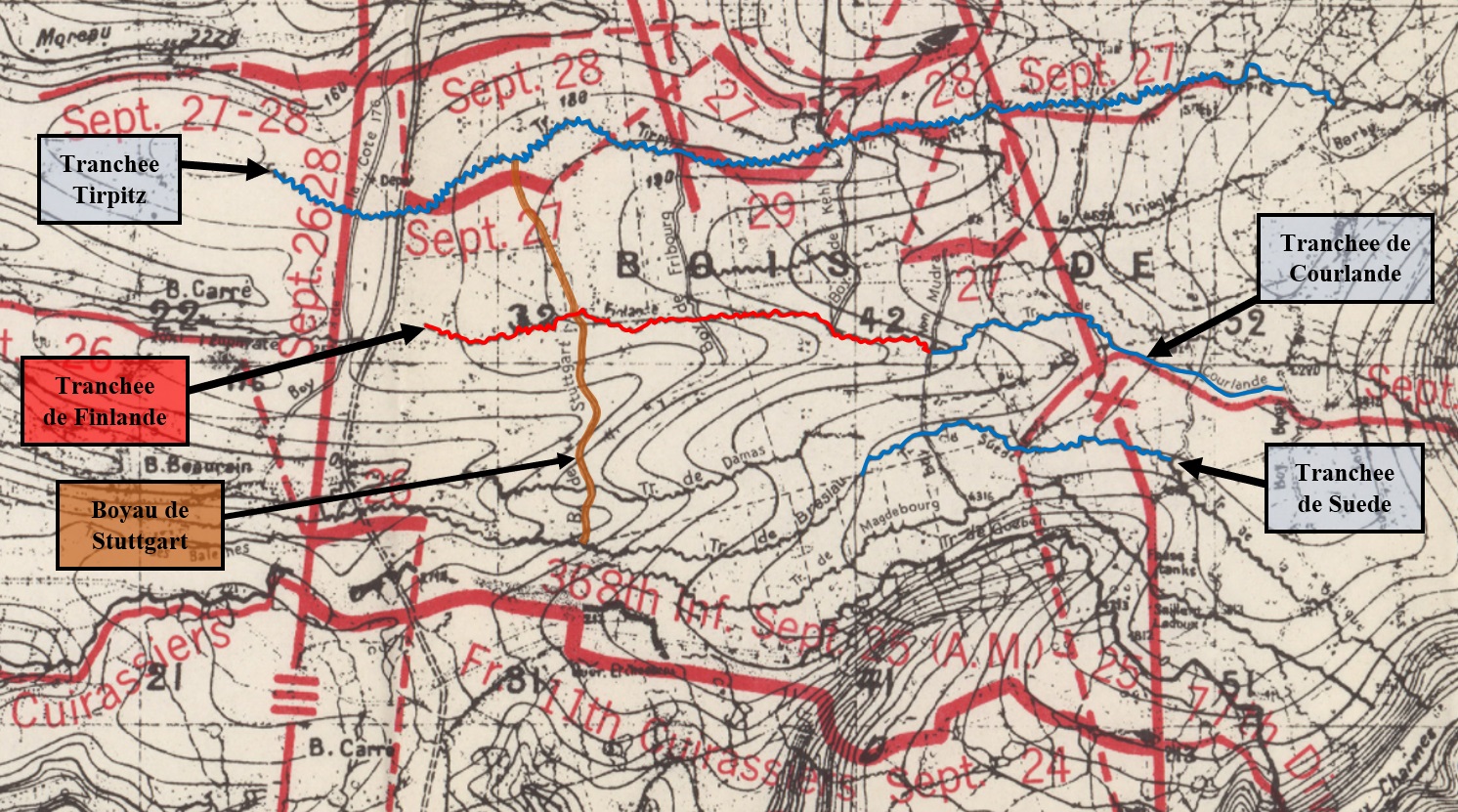

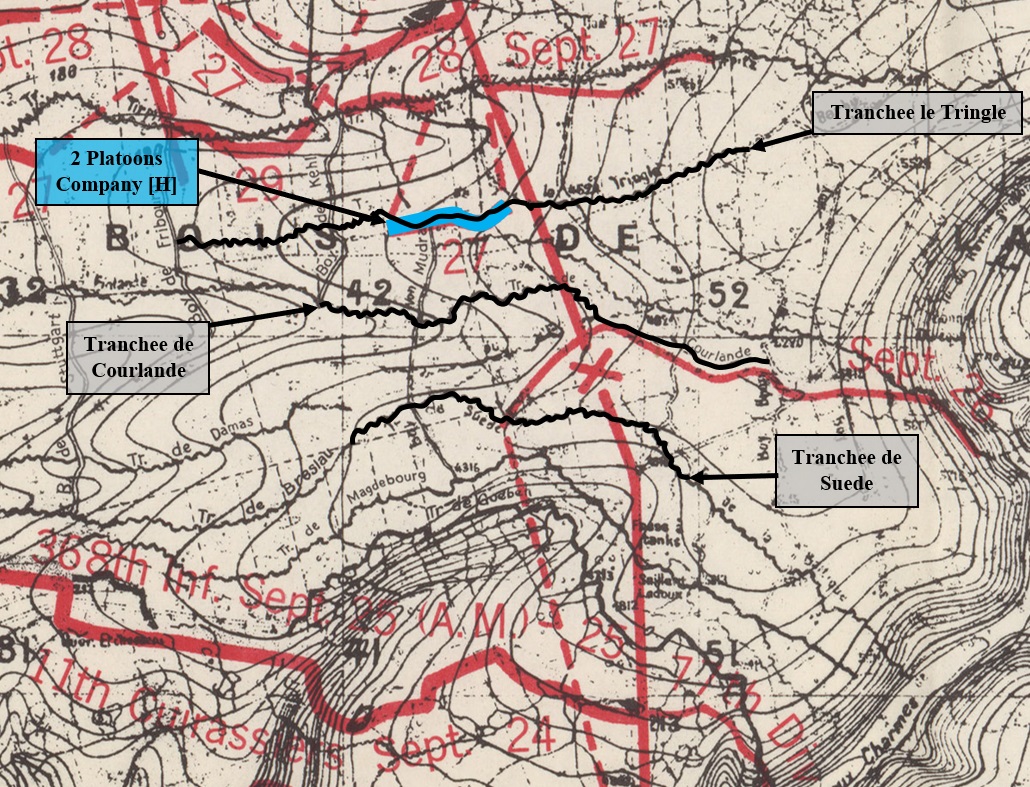

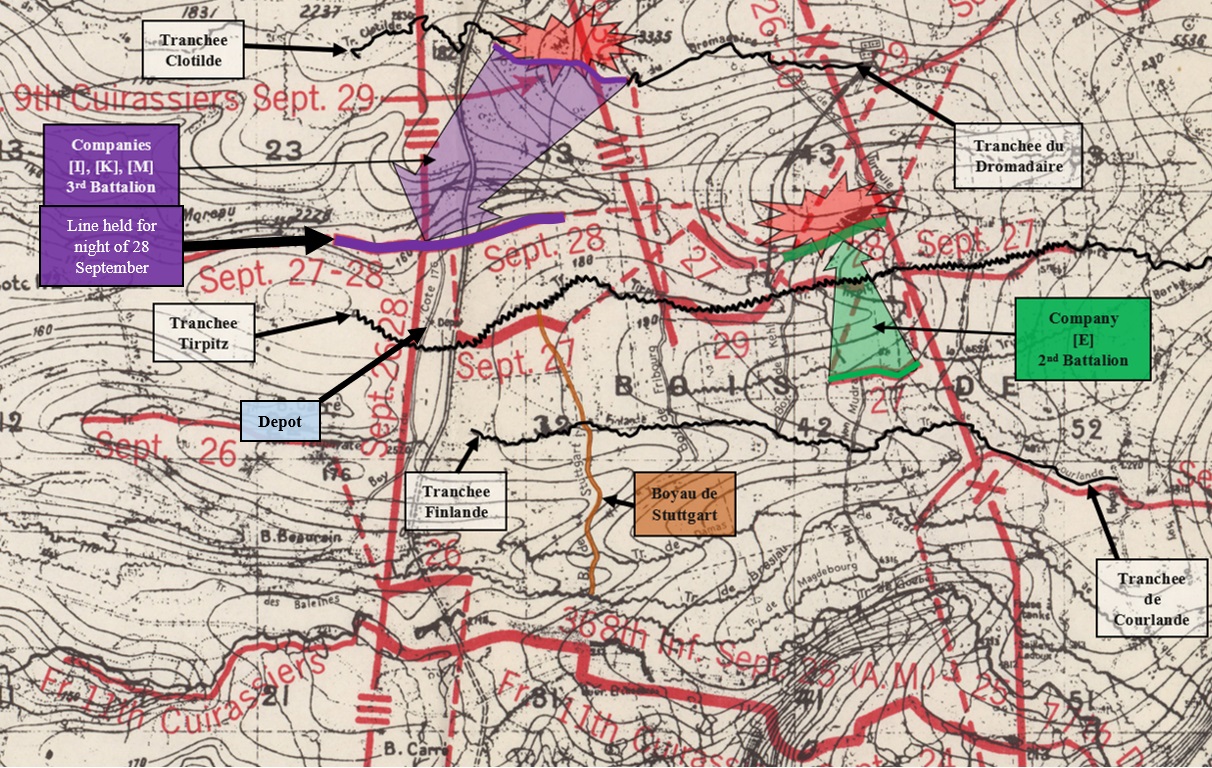

Companies [E] and [H] advanced with four machine-guns with Major Elser and had crossed Tranchee de Suede to reach the area of Tranchee de Courlande. During their advance they had encountered strong German machine-gun fire, although there was no liaison to either flank and forward patrols had not disclosed any German positions, the companies managed to isolate and silent the machine-gun nests and killed three German soldiers in the process.

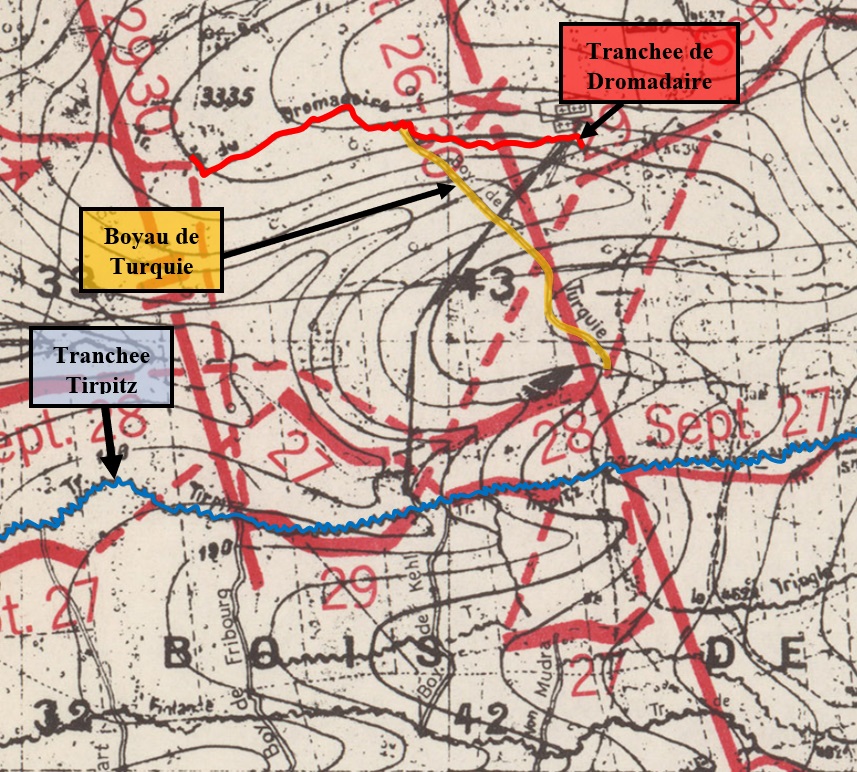

Meanwhile, Company [F] reached the first line German trenches without any opposition and split into two groups consisting of two platoons each. One group of Company [F] managed to reach Tranchee Tirpitz and capture one German prisoner and one machine-gun, killing three Germans in the process; however, the group was forced to withdraw back to their position in the first German trench they had reached. The other group of Company [F] were unable to reach Tranchee Tirpitz and had only advanced to Ravine des Neirailieuses, but were also driven back to their original departure point.

Company [G] spent the day working through the heavy-barbed wire and trenches, although it carried out its mission with a scout platoon the company didn’t progress far throughout the day.

At 0800 hours (8:00 A.M.), Major Elser headed to the regimental command post after having “temporarily los[ing] his way.” Two hours later around 1000 hours (10:00 A.M.), the 2nd Battalion advanced 1.5 kilometers without much opposition from German forces. At 1035 hours(10:35 A.M.), Colonel Brown reported to the division stating that the 2nd Battalion was “against [German] wire and working their way through… with no tools nor artillery preparation passage of enemy’s wiring is very difficult.”

At 1100 hours (11:00 A.M.), one of the groups from Company [F] of 2nd Battalion had advanced to Tranchee de Finlande via Boyau de Stuttgart was was temporarily held up by intense German machine-gun fire. During the engagement against the German machine-guns, the group had taken one prisoner and killed six other German soldiers.

Around 1300 hours (1:00 P.M.), the 3rd Battalion of the 368th Infantry moved to the line of trenches located about 350 meters in the rear of the French frontline, and detachments of Company [K] of 3rd Battalion had operated as a liaison to both flanks of the 368th Infantry Regiment excluding one group that remained with 2nd Battalion’s Company [F].

At 1315 hours (1:15 P.M.), after crossing Tranchee Tirpitz Companies [E] and [H] of 2nd Battalion resumed their advance along the narrow-gauge railroad that paralleled Boyau de Turquie. As they advanced, the group quickly encountered German rear-guard machine-guns which halted their movement. Reconnaissance and reorganization was implemented during the halt but the men had trouble locating the direction of the incoming German machine-gun fire through the mangled trees, smoke and fog which limited visibility to only a few yards.

At 1315 hours (1:15 P.M.), after crossing Tranchee Tirpitz Companies [E] and [H] of 2nd Battalion resumed their advance along the narrow-gauge railroad that paralleled Boyau de Turquie. As they advanced, the group quickly encountered German rear-guard machine-guns which halted their movement. Reconnaissance and reorganization was implemented during the halt but the men had trouble locating the direction of the incoming German machine-gun fire through the mangled trees, smoke and fog which limited visibility to only a few yards.

By 1430 hours (2:30 P.M.) the liaison detachments of the 3rd Battalion, as well as portions of Company [E] of 2nd Battalion had lost contact with the American 77th Division to the east of the 368th Infantry. As the day progressed, contact with the west element of Groupement Durand in the French 11th Cuirassiers was lost. Subsequently, a platoon of Company [M] from 3rd Battalion was sent south to Ravin de l’Artillerie in an attempt to reestablish contact with the left element of the 368th Infantry. This platoon was not only unsuccessful in reestablishing contact, but didn’t return to Company [M] for the remainder of the operation.

The 2nd Battalion commander, Major Elser, still had not been found since his visit to regimental headquarters in the morning, and all communication between him, other companies, his battalion, as well as headquarters were completely lost.

By 1630 hours (4:30 P.M.) the thick barbed-wire, maze of trenches and German defense systems, smoke, mud and fog had taken its toll on the inexperienced officers of the 2nd Battalion, 368th Infantry Regiment. As a result, the 2nd Battalion was in near complete disarray, its elements were dispersed into platoons and section units across the sector with little-to-no leadership. To make matters worse, German airplanes were dropping bombs which resulted in shrapnel and increased terror among the troops. Confusion increased as the sun began to set and the companies of 2nd Battalion became even more scattered with communication being lost and movements disjointed.

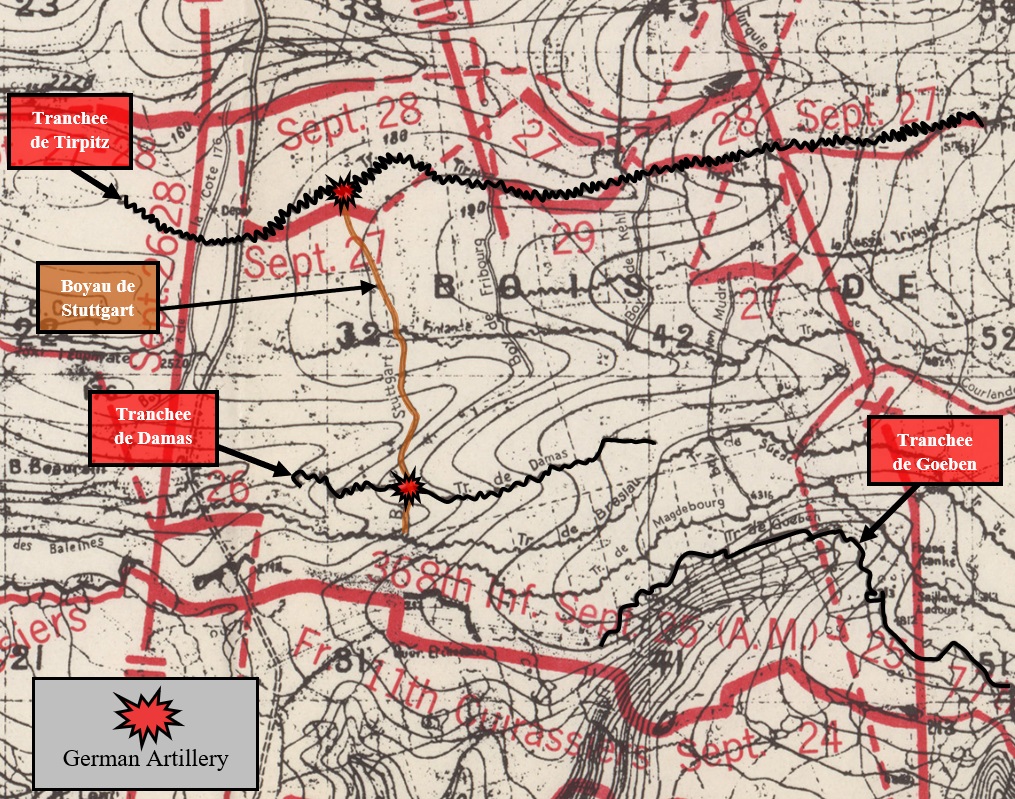

At 1730 hours (5:30 P.M.), two platoons of Company [F] were forced to withdrawal from their positions and relocate to the ravine in rear of Tranchee de Damas due to heavy German artillery fire. Once relocated, the German artillery began bombarding this position as well and the two platoons were forced to relocate further south of Tranchee de Goeben, where they stayed for the remainder of the night.

Later in the day, the 1st Battalion of the 368th Infantry who were serving as the divisional reserve had moved forward from their position in Haute Batis to P.C. Capinere.

By 2100 hours (9:00 P.M.), Company [F]’s platoons had managed to reach the German frontline trenches. Captain James Wormley Jones of Company [F] had pushed his men forward in heavy German fire until they had crossed nearly 1.5 kilometers of “no-man’s land.” As the sun set, the smoke and fog over the battlefield had thickened and these platoons used the cover to its advantage in concealing its movements as it cut through the barbed-wire, cleared machine-gun nests, and bombed German dugouts in order to safely maintain their position for the night.

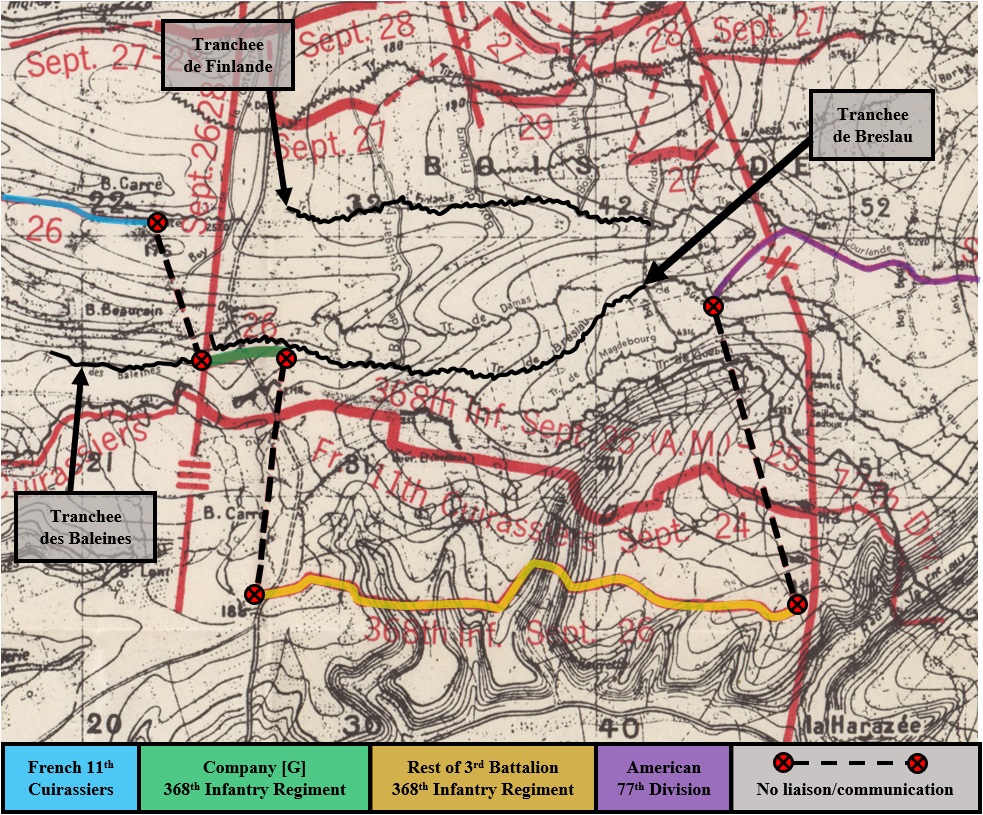

Company [F]’s platoons, as well as a liaison group from Company [K], had advanced to the ravine south of Tranchee de Finlande. However, they soon received intense German artillery fire that forced them to withdrawal south of Tranchee de Breslau where they spent the remainder of the night.

Company [F]’s platoons, as well as a liaison group from Company [K], had advanced to the ravine south of Tranchee de Finlande. However, they soon received intense German artillery fire that forced them to withdrawal south of Tranchee de Breslau where they spent the remainder of the night.

As a result of the chaotic movements throughout the day, both groups of platoons from Company [F] were not in communication with any other units throughout the night. By dark, Groupement Durand had failed in its mission maintain liaison between the French Fourth Army and the American First Army due to the disorganized movements of its elements throughout the day.

Company [G], 2nd Battalion, which was located on the left of the assault of the 368th Infantry throughout the day had reached Tranchee des Baleines. This position was held for the night with 3d Battalion’s Company [M] in support. Although liaison was maintained with the French 11th Cuirassiers, there was no liaison with any its units within the frontlines of the French 11th Cuirassiers located around Tranchee de l’Euphrate. Companies [E] and [H], 2nd Battalion, which assaulted as the right element of the 368th Infantry had withdrawn for the evening and took positions in the rear of the line of 3rd Battalion, 368th Infantry.

Two soldiers from the Landwehr-Infanterie-Regiment Nr. 83 (83rd Landwehr Regiment, 9th Landwehr Division) on the Western Front

The 368th Infantry Regiment Commander, Colonel Frederick R. Brown, reported that the 2nd Battalion had captured a single German prisoner from the German 7th Company, 2nd Battalion. Which was a part of the German 83rd Landwehr Regiment (Infantry), 76th Landwehr Infantry Brigade, 9th Landwehr Division, Group Argonne, Army Group Crown Prince, German Third Army.

At 2359 hours (11:59 P.M.), the line of the 3rd Battalion, 368th Infantry was the only organized line of the 368th Infantry Regiment, extending about 600 meters across, excluding the portion of Company [G] lines in Tranchee des Baleines. Elements of the 2nd Battalion, 368th withdrew through portions of the 3rd Battalion during the night. However, the scattered groups of Companies [E], [F], and [H], 2nd Battalion, were located just ahead of the 3rd Battalion line and not in contact with the 3rd Battalion nor any other elements.

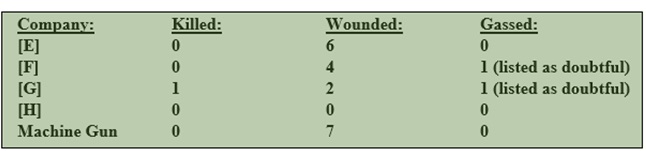

Overall, on the first day of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, the 2nd Battalion of the 368th Infantry reported the following casualties:

—

Misinterpretations of History

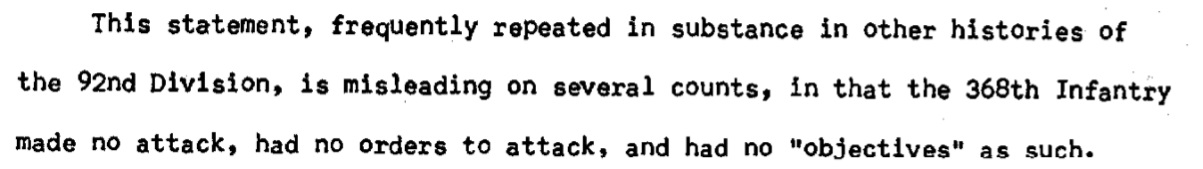

Military documentation can often be subject to interpretation and thereby support, contradict, or convolute historical fact. It is up to the researcher to maintain an objective position and verify information in meticulous investigation of sources and documents, as sources may misinterpret information and lead to an inaccurate recount of events. In the case of the operations and orders of the 368th Infantry Regiment and its activities for the 26 and 27 September 1918, the U.S. Army Chemical Corps Historical Studies, Gas Warfare In World War I: The 92nd Division in the Marbache Sector October 1918 states on page 11 that the “368th Infantry made no attack, had no orders to attack, and had no “objectives” as such.”

However, this is inaccurate and based on the orders the 368th Infantry received on the 25 September 1918 orders of maintaining liaison between the French Fourth Army and American First Army, and keeping the German infantry under surveillance. Even so, it disregards the assignment of assault battalions in Groupement Durand including the 2nd Battalion, 368th Infantry Regiment by the French Fourth Army in orders given on the same day as supported in documentation such as the reports of operations of companies [E], [F], and [H], 368th Infantry, 26-30 September 1918; Report of Operations, 2nd Battalion, 368th Infantry, 26-30 September 1918; Field Message, 368th Infantry to Groupement Durand, 8 P.M., 26 September 1918; and the Report of Operations, 368th Infantry, 15 November 1918.

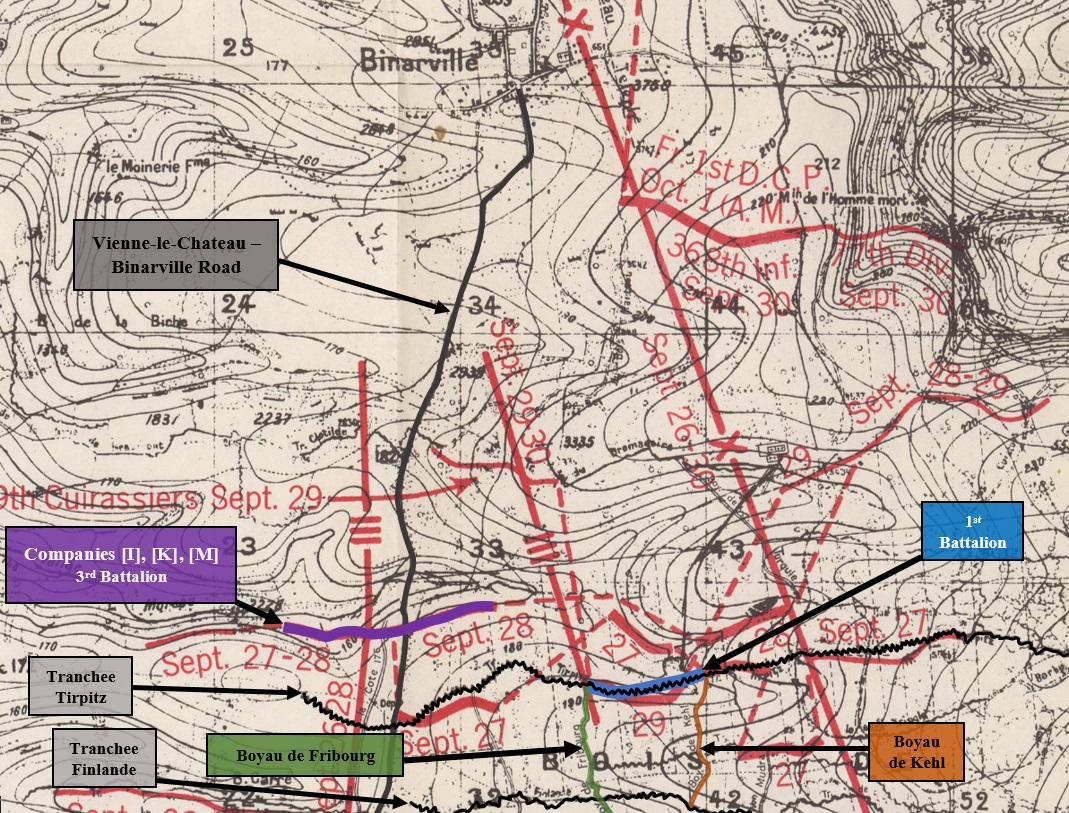

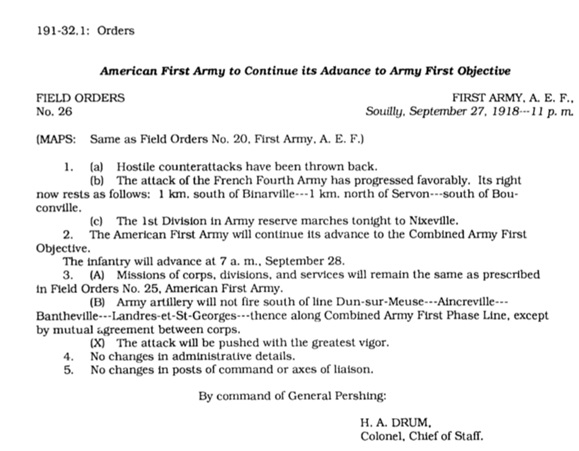

According to pages 14-15 to the 92nd Division Summary of Operations in the World War, prepared by the American Battle Monuments Commission, the French 1st Dismounted Cavalry, French XXXVIII Corps, French Fourth Army ordered a continuation of attack for the 27 September 1918 on both sides of the Aisne River. Within these orders, Groupement Durand were specifically directed to reconnoiter the German points of resistance at daybreak, then advance throughout the day to Tranchee de la Palette – Tranchee de Charlevaux – North of Binarville-Autry Road.

The United States Army in the World War 1917-1919: Military Operations of the American Expeditionary Forces Volume 9 from the Center of Military History supports that the 368th Infantry were, in fact, directed by the French Fourth Army in a continuation of attack. Dated 27 September 1918 and located on page 140, Field Orders No. 26, 1(b) can be seen stating that “the attack of the French Fourth Army has progressed favorably. Its right now rests as follows: 1km south of Binarville — 1km north of Servon — south of Bouconville.” This provides further support in that the French Fourth Army did give orders to its units, including Groupement Durand whom was in the area of Binarville on 27 September, for a continuation of attack.

The United States Army in the World War 1917-1919: Military Operations of the American Expeditionary Forces Volume 9 from the Center of Military History supports that the 368th Infantry were, in fact, directed by the French Fourth Army in a continuation of attack. Dated 27 September 1918 and located on page 140, Field Orders No. 26, 1(b) can be seen stating that “the attack of the French Fourth Army has progressed favorably. Its right now rests as follows: 1km south of Binarville — 1km north of Servon — south of Bouconville.” This provides further support in that the French Fourth Army did give orders to its units, including Groupement Durand whom was in the area of Binarville on 27 September, for a continuation of attack.

27 September 1918:

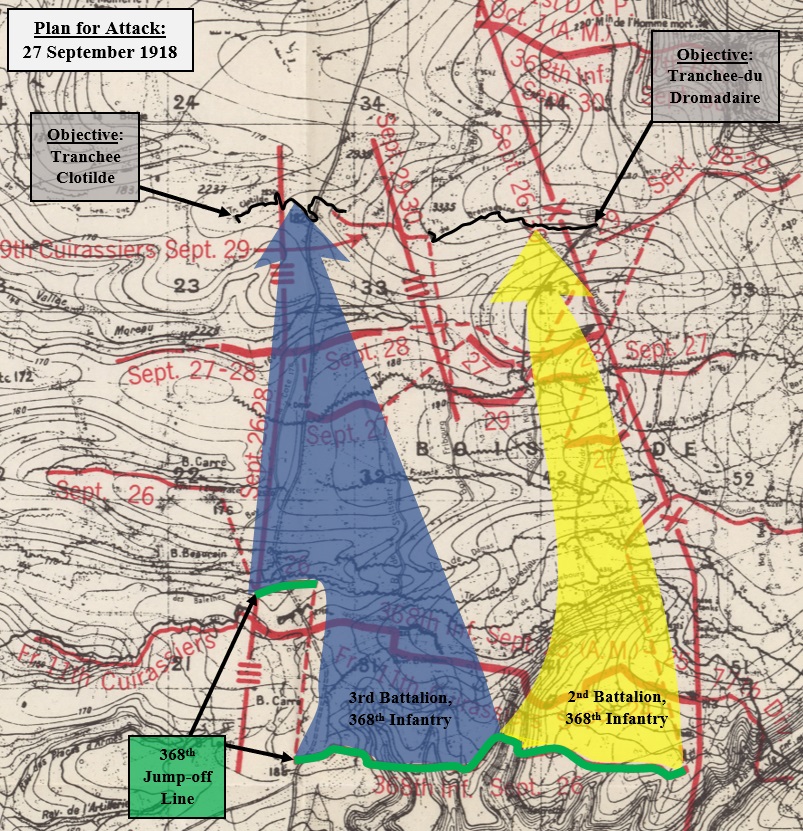

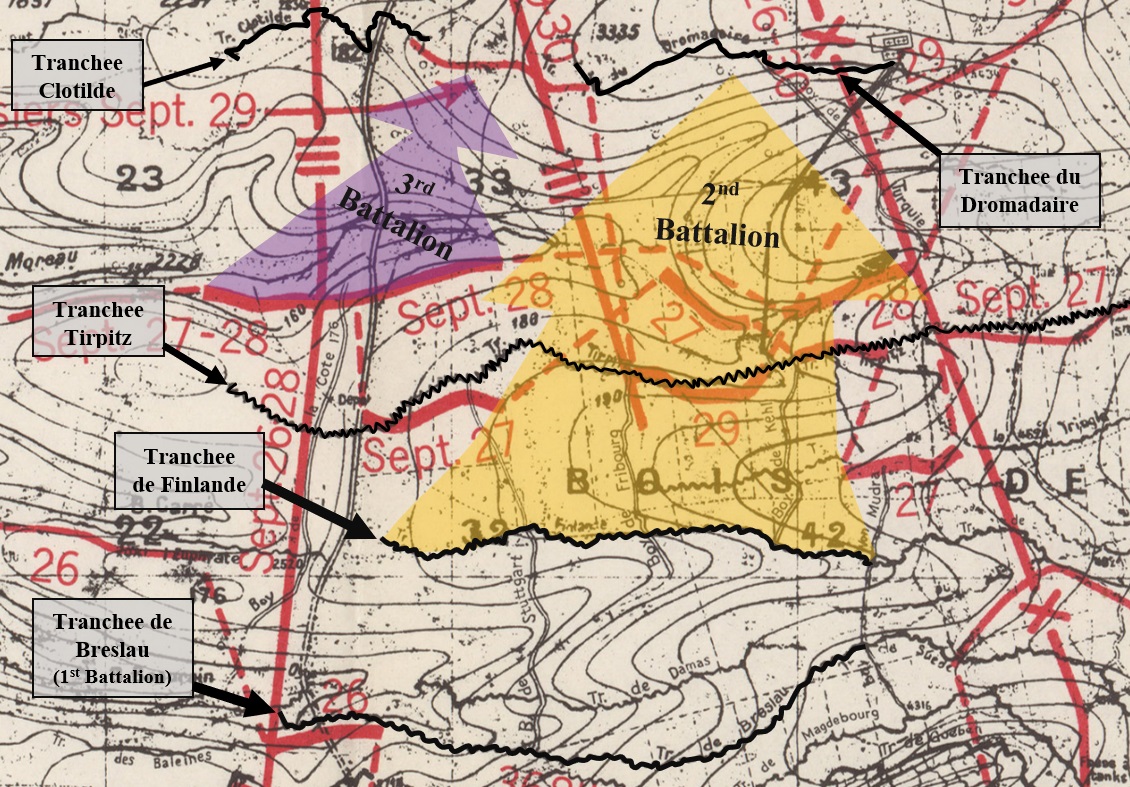

At 0345 hours (0345 A.M.) the 368th Infantry received Ordre No. 27 by the French 1st Dismounted Cavalry Division (D.C.P.) to advance to the line of Tranchee-du Dromadaire – Tranche Clotilde at 0515 hours (5:15 A.M.). The objectives were located 2 kilometers within the German lines, but the French 1st D.C.P. placed a group of 75mm artillery guns at the disposal of the 368th Infantry and Groupement Durand. The orders given had specified that the 368th would attack with the 3rd Battalion on the left and the 2nd Battalion on right, while the 1st Battalion would remain in reserve.

At 0345 hours (0345 A.M.) the 368th Infantry received Ordre No. 27 by the French 1st Dismounted Cavalry Division (D.C.P.) to advance to the line of Tranchee-du Dromadaire – Tranche Clotilde at 0515 hours (5:15 A.M.). The objectives were located 2 kilometers within the German lines, but the French 1st D.C.P. placed a group of 75mm artillery guns at the disposal of the 368th Infantry and Groupement Durand. The orders given had specified that the 368th would attack with the 3rd Battalion on the left and the 2nd Battalion on right, while the 1st Battalion would remain in reserve.

The 2nd Battalion was in complete disorganization when they received their attack orders around 0430 hours (4:30 A.M.). The morning was spent assembling the battalion to prepare for the attack. The reorganization of the scattered units had caused a delay in the time of attack with another reason for delay back at Regimental Headquarters. Major Elser, commander of the 2nd Battalion had reported back to the line earlier in the morning, was in the middle of a tense conversation with the 368th Infantry Regiment commander, Colonel Fred Brown, when the time of attack had come. Major Elser suggested that the 2nd and 3rd Battalion not attack side-by-side, but rather “leap-frog” (bounding overwatch technique) the battalions to give Elser time to recognize his men. However, Colonel Brown dismissed Elser’s request and refused to change the orders given by the French 1st D.C.P. Nonetheless, the attack commenced with the elements of the 368th making advances at different times throughout the day.

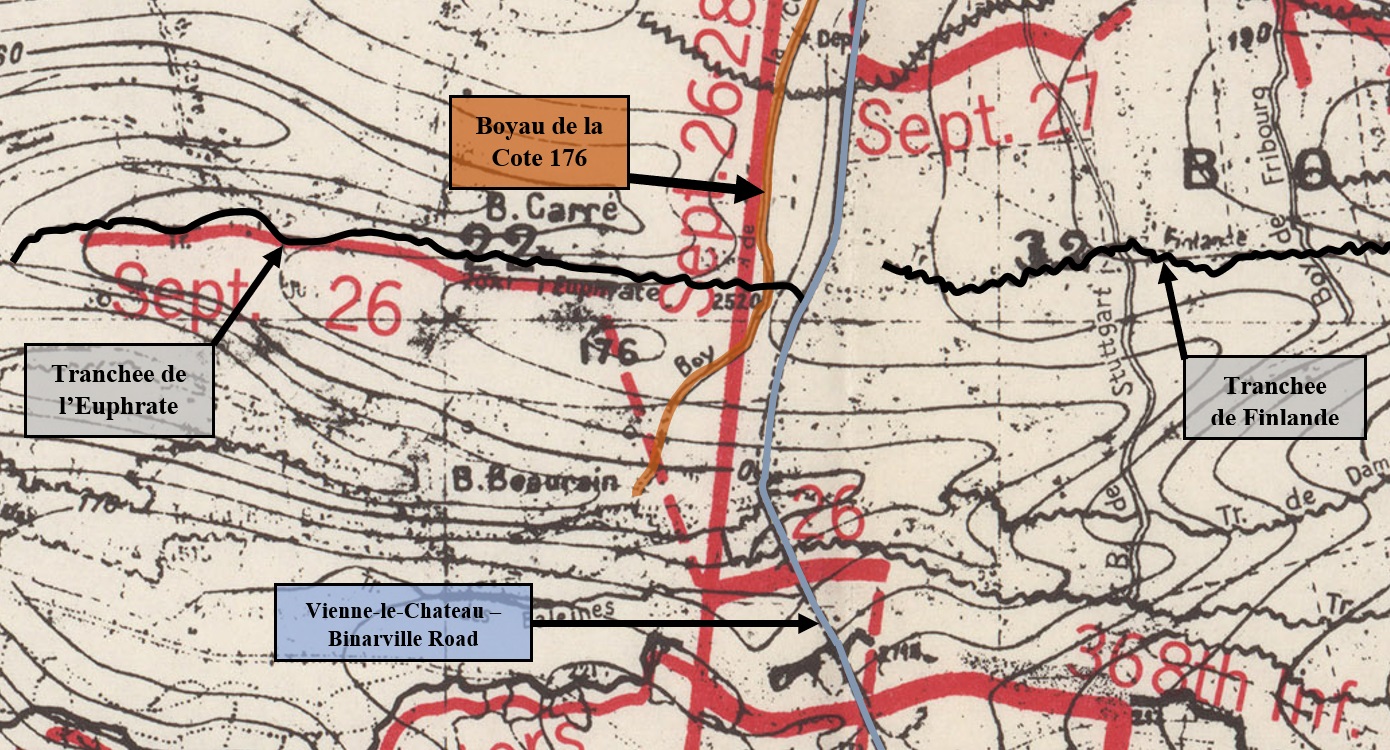

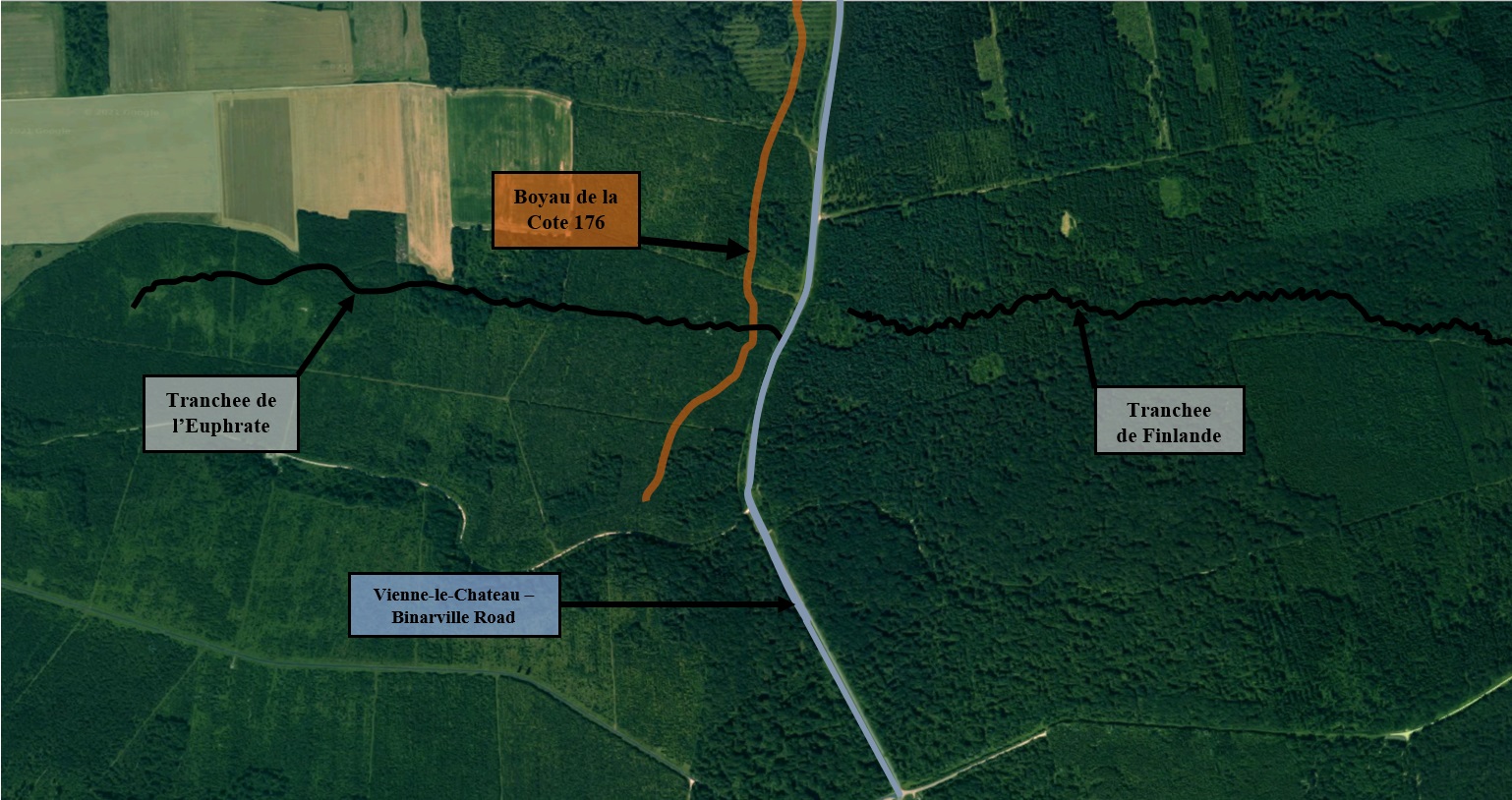

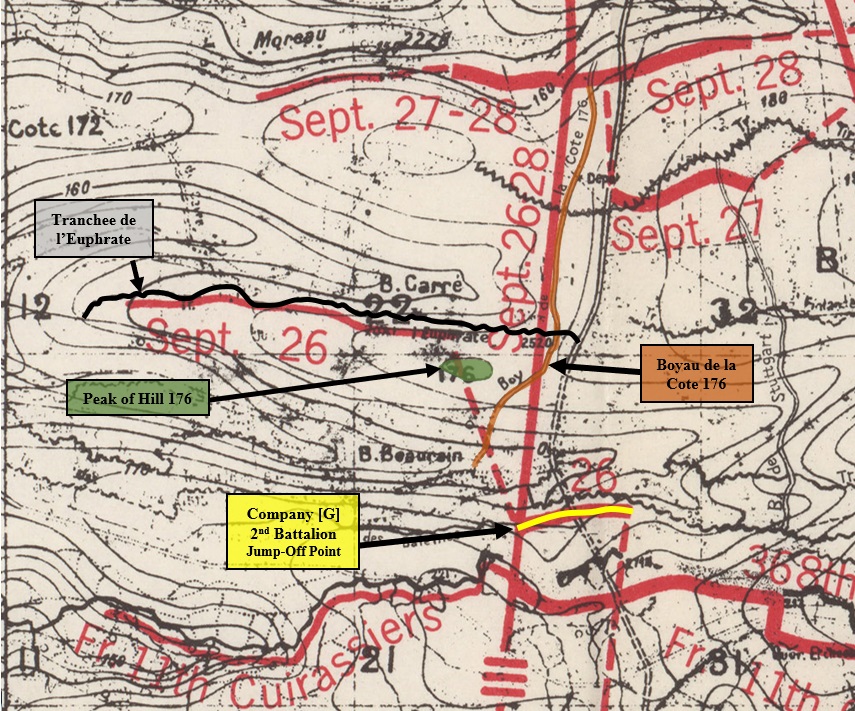

Regardless of the delay, Company [G], 2nd Battalion advanced from its position in Tranchee des Baleines until it was stopped by German machine-gun fire at Tranchee de l’Euphrate.

At 0730 hours (7:30 A.M.), the 3rd Battalion advanced in its zone of action from Boyau-de-Stuttgart, and reached a portion of the trench at Tranchee de l’Euphrate.

Around 0900 hours (9:00 A.M.), Company [G], 2nd Battalion established contact with the French 11th Cuirassiers while Company [I] supported Company [M], 3rd Battalion in their advance to the northwest over Hill 176. During its movement, Company [M], 3rd Battalion got into position behind Company [G], 2nd Battalion in an advance to Tranchee de l’Euphrate and remained south of the trench. Meanwhile, Company [K] assembled in preparation for an afternoon attack.

Around 0900 hours (9:00 A.M.), Company [G], 2nd Battalion established contact with the French 11th Cuirassiers while Company [I] supported Company [M], 3rd Battalion in their advance to the northwest over Hill 176. During its movement, Company [M], 3rd Battalion got into position behind Company [G], 2nd Battalion in an advance to Tranchee de l’Euphrate and remained south of the trench. Meanwhile, Company [K] assembled in preparation for an afternoon attack.

At 1130 hours (11:30 A.M.), elements of the 2nd Battalion launched an attack from Ravin de del Adri and advanced around 2 kilometers against German machine-gun fire before it was halted. The forward companies remained in position throughout the day and night until the morning of the following day.

At 1200 hours (12:00 P.M.), Company [G], 2nd Battalion was withdrawn from Tranchee de l’Euphrate and moved under cover of a ravine to Tranchee de Finlande to prepare for its afternoon attack. After Company [G] withdrew, Company [M] of 3rd Battalion moved to the east so that its right flank rested on the Vienne-le-Chateau – Binarville Road, forward to occupy Tranchee de l’Euphrate against slight German resistance.

Meanwhile, an assault on portions east and west of Vienne-le-Chateau – Binarville Road in and near Tranchee Tripitz and in Vallee Moreau with Company [E] acting as support to Company [H] of the 2nd Battalion. Company [H], 2nd Battalion assembled in Tranchee de Suede with Company [E] in support earlier in the day. At 1200 hours (12:00 P.M.) Company [H] advanced two platoons to Tranchee le Tringle and was supported by the remaining elements of Company [H] in Tranchee de Courlande. These platoons remained in their position until 0300 hours (3:00 A.M.) the following morning. Although the advance was considered successful, liaison was still unestablished on both flanks throughout the day and night despite efforts made by Company [E] to reestablish communication with the 77th Division to the east.

The 2nd Battalion of the 368th made an advance at 1230 hours (12:30 P.M.), but the assault quickly fell apart when Major Elser lost communication with his companies, and the company commanders lost communication with their platoons. The soldiers lacked maps and had quickly gotten lost their sense of direction within the dense woods. In the meantime, the 3rd Battalion formed an organized line on the left sector of the 368th zone of action and were preparing for an assault planned for 1730 hours (5:30 P.M.).

During the day, the 1st Battalion, acting as reserve, relocated north to the Biesme River in the area of Vienne-la-Chateau.

During the day, the 1st Battalion, acting as reserve, relocated north to the Biesme River in the area of Vienne-la-Chateau.

At 1630 hours (4:30 P.M.), Companies [F] and [G] of 2nd Battalion advanced from Tranchee de Finlande toward Tranchee Tirpitz. Company [G], on the right, reached Tranchee Tirpitz in the area of Boyau de Kehl and halted its advance to remain in its position for the rest of the night. Meanwhile, Company [F], located on the left, had advanced past Tranchee Tirpitz and was examining the ravine to the north when patrols from Company [F] working their way northeast had encountered German machine-gun resistance.

At 1630 hours (4:30 P.M.), Companies [F] and [G] of 2nd Battalion advanced from Tranchee de Finlande toward Tranchee Tirpitz. Company [G], on the right, reached Tranchee Tirpitz in the area of Boyau de Kehl and halted its advance to remain in its position for the rest of the night. Meanwhile, Company [F], located on the left, had advanced past Tranchee Tirpitz and was examining the ravine to the north when patrols from Company [F] working their way northeast had encountered German machine-gun resistance.

Company [F] was the most exposed unit of the 368th, and was forced to fall back from its position at 2200 hours (10:00 P.M.) to a less exposed position just north of Tranchee Tirpitz due to German machine-gun, artillery, and airplane fire that consistently rained down on it. Due to the chaos of the German resistance, Companies [F] and [G] lost contact with one another.

At 1730 hours (5:30 P.M.), Companies [I], [K], and [M] of 3rd Battalion attacked northward with Company [M] on the left, Company [I] in the center, and Company [K] on the right. Companies [I] and [M] followed the Vienne-le-Chateau – Binarville Road as Company [M] stayed to the left of the road and remained in contact with the French 11th Cuirassiers. Around 1900 hours (7:00 P.M.), the advance by the companies came to a halt and Companies [I] and [K] took positions extending from the road to about 400 meters east on a line Depot – Tranchee Tirpitz. Company [M] extended itself to the west by approximately 500 meters and set-up an outpost to the northeast, liaison had not been maintained between Company [M] and Companies [I] and [K]. Company [M] had also lost contact with the French 11th Cuirassiers, who were located to the west of Company [M].

To prepare for the upcoming attack on the following day, the Machine-Gun Company of 1st Battalion was divided between the 2nd and 3rd Battalions, and the 2nd and 3rd Battalions attached the elements of the Machine-Gun Company to their assault battalions. An additional unit from the French 10th Dragoons were also attached to Groupement Durand.

To prepare for the upcoming attack on the following day, the Machine-Gun Company of 1st Battalion was divided between the 2nd and 3rd Battalions, and the 2nd and 3rd Battalions attached the elements of the Machine-Gun Company to their assault battalions. An additional unit from the French 10th Dragoons were also attached to Groupement Durand.

Meanwhile, the German Third Army, for whom the 368th Infantry faced, placed additional reserves in the Champagne region. However, the German Third Army lacked the necessary reserves to protect its boundary with the German Fifth Army on its eastern flank, subsequently all of the reserve units were placed in combat positions.

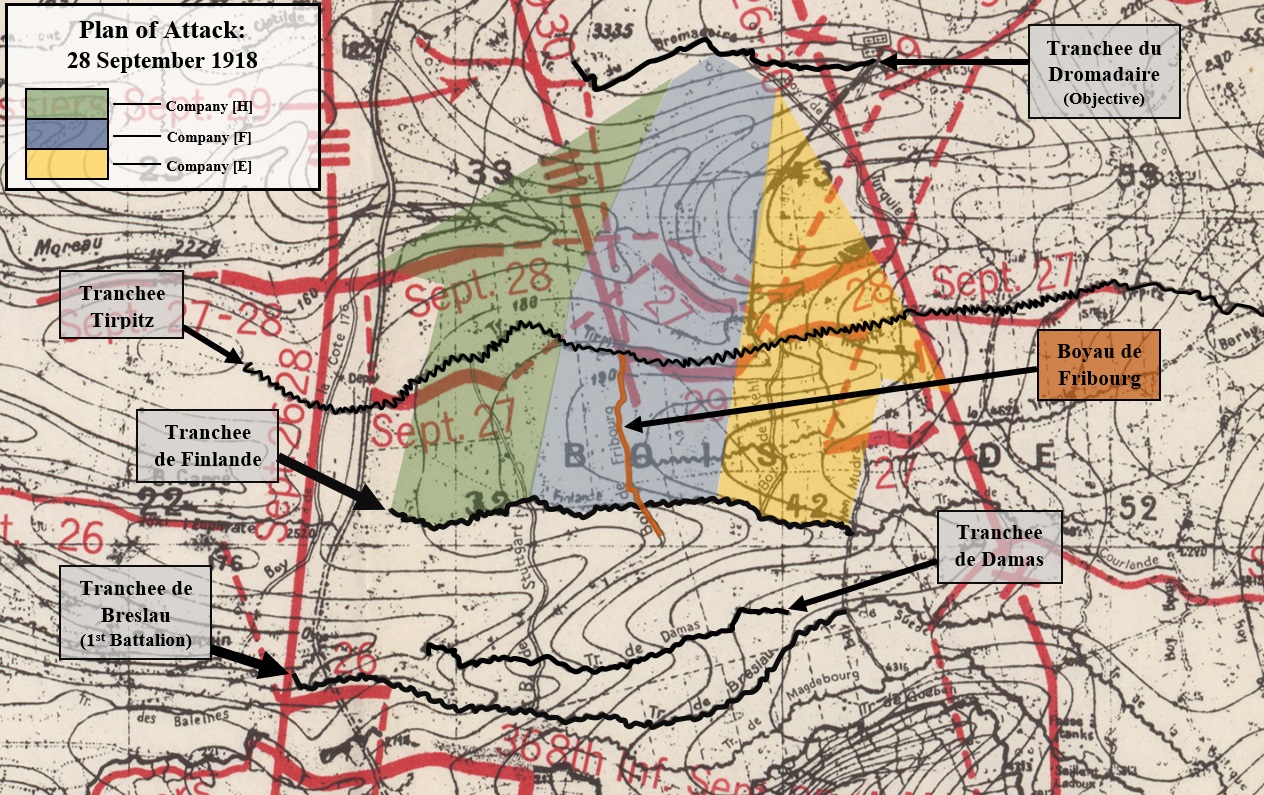

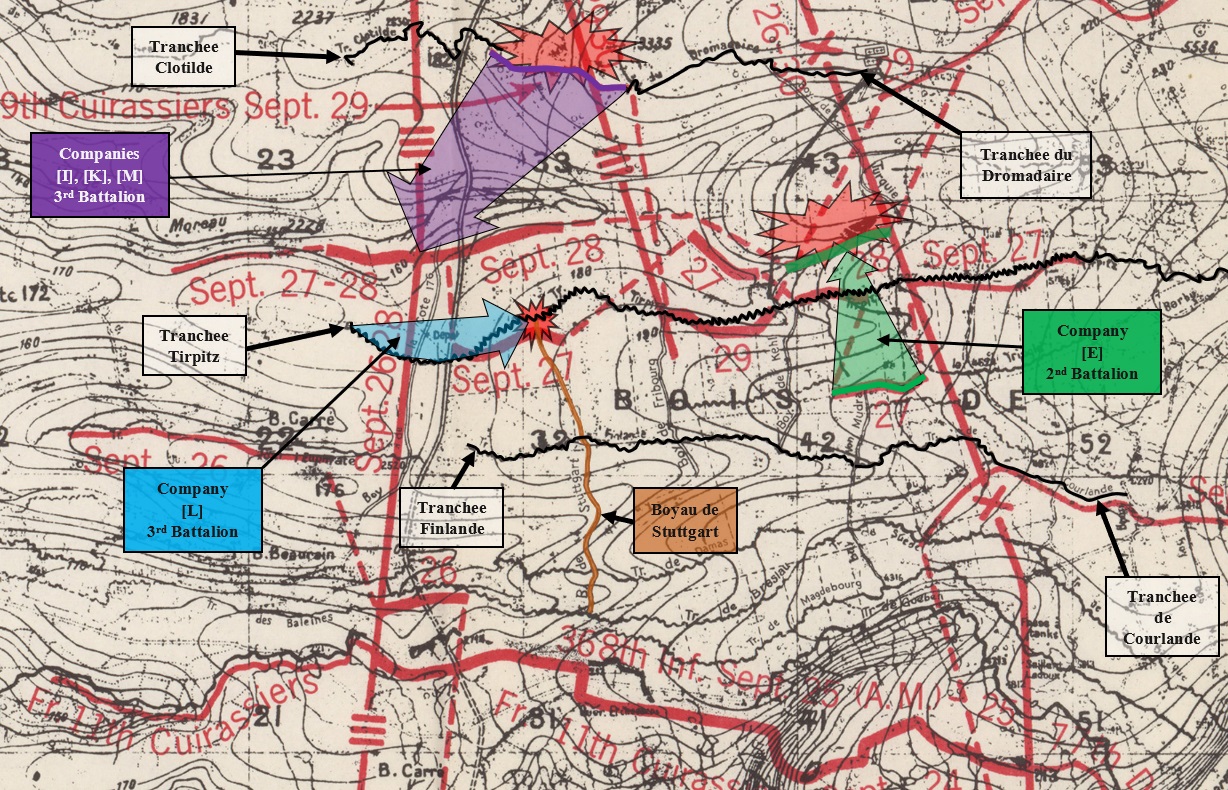

28 September 1918:

At 0215 hours (2:15 A.M.), the French 1st D.C.P. directed the 368th Infantry to attack in the direction of Binarville, France astride the Vienne-le-Chateau – Binarville Road. The 368th was reinforced by a squadron from the French 10th Dragoons, they were to proceed the advance of the 368th and maintain liaison with the French 11th Cuirassiers to keep them informed them of the situation in the area of Binarville. Along with the French 10th Dragoons, a group of 75mm and 105mm artillery guns were placed at the disposal of the 368th.

The 368th Infantry began preparations for its assault on Binarville and the surrounding area. Around 0225 hours (2:25 A.M.), a group of French 75mm guns and two companies of the 351st Machine-Gun Battalion were instructed to direct their assault toward the town of Binarville. At 0300 hours (3:00 A.M.), Companies [E] and [H], 2nd Battalion of the 368th moved to Tranchee de Damas to receive rations and supplies. Company [G] withdrew from its position in Tranchee Tirpitz and relocated to Tranchee Finlande at 0400 hours (4:00 A.M.) under German artillery and machine-gun fire.

Preparation for Attack:

In the early morning of 28 September 1918, the 1st Battalion, 368th Infantry continued serving as division reserve for the French 1st D.C.P. were ordered to move to Tranchee de Breslau and prepare for possible German counterattacks from the east and northeast. They were to hold their positions for the day and were ordered to determine the exact positions of the 2nd and 3rd Battalions of the 368th, as well as establish communication with the American 77th Division located to the right flank.

The 2nd Battalion remained disorganized and needed to reestablish positions along a coordinated front. Subsequently, Company [E] reorganized itself and was placed on the right flank in Tranchee de Finlande. Company [F] was the most forward element of the 2nd Battalion and had to relocate from its positions north of Tranchee Tirpitz at 0500 hours (5:00 A.M.) to Tranchee de Finlande, and upon its southward movement Company [F] reorganized its scattered detachments and reached Tranchee de Finlande by 1100 hours (11:00 A.M.). Company [G] assembled in Tranchee de Finlande and was placed in support while Company [H] moved from Tranchee de Damas to Tranchee Tirpitz, where they paralleled Boyau de Fribourg.

Overall, the 2nd and 3rd Battalion were given the task of capturing Tranchee du Dromadaire, with their original zones of attack being unchanged from its previous orders.

At about 0645 hours (6:45 A.M.), although the sun had risen the visibility on the battlefield was low due to the overcast skies and rain, and around 0730 hours (7:45 A.M.), the 3rd Battalion was located abreast the 2nd Battalions left flank with Companies [I], [K] and [M] with Company [L] serving as reserve. The 3rd Battalion began a forward advance of 2 kilometers toward a position south of the line Tranchee du Dromadaire – Tranche Clotilde, facing little opposition in its initial crossing of Valle Moreau in the process. Company [M] was the leftmost element, Company [I] was in the center, and [Company K] was the right element of the 3rd Battalion’s advance.

At about 0645 hours (6:45 A.M.), although the sun had risen the visibility on the battlefield was low due to the overcast skies and rain, and around 0730 hours (7:45 A.M.), the 3rd Battalion was located abreast the 2nd Battalions left flank with Companies [I], [K] and [M] with Company [L] serving as reserve. The 3rd Battalion began a forward advance of 2 kilometers toward a position south of the line Tranchee du Dromadaire – Tranche Clotilde, facing little opposition in its initial crossing of Valle Moreau in the process. Company [M] was the leftmost element, Company [I] was in the center, and [Company K] was the right element of the 3rd Battalion’s advance.

At 1125 hours (11:25 A.M.), as the 3rd Battalion approached the line of Tranchee du Dromadaire – Tranchee Clotilde, two urgent field messages from the 368th command were received by the 2nd Battalion. The field messages ordered the advance of the 2nd Battalion and capture of Tranchee du Dromadaire from the Germans to protect the right flank of the 3rd Battalion.

At 1125 hours (11:25 A.M.), as the 3rd Battalion approached the line of Tranchee du Dromadaire – Tranchee Clotilde, two urgent field messages from the 368th command were received by the 2nd Battalion. The field messages ordered the advance of the 2nd Battalion and capture of Tranchee du Dromadaire from the Germans to protect the right flank of the 3rd Battalion.

Around noon, the 3rd Battalion continued to advance but were soon met by German machine-gun fire and grenades, the 3rd Battalion were forced to stopped. Although the 3rd Battalion had artillery support, it had minimal effect and the 3rd Battalion quickly became disorganized while confusion ensued. As a result, the 3rd Battalion expected the 2nd Battalion to assist them, however, the 2nd Battalion were under pressure of their own.