News & Events

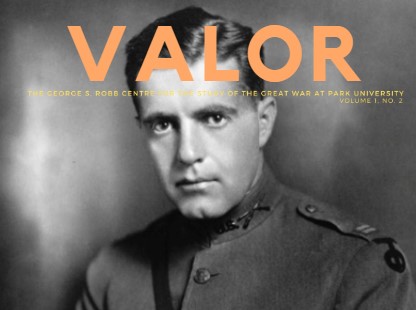

The George S. Robb Centre and its endeavors are vital to its mission. We are appreciative of the media we have appeared in and the events hosted throughout the years. This page hosts digital copies of our biannual Valor magazine, written and published by the George S. Robb Centre staff, as well as our celebration of diversity in our Heritage Month videos.

Past Events

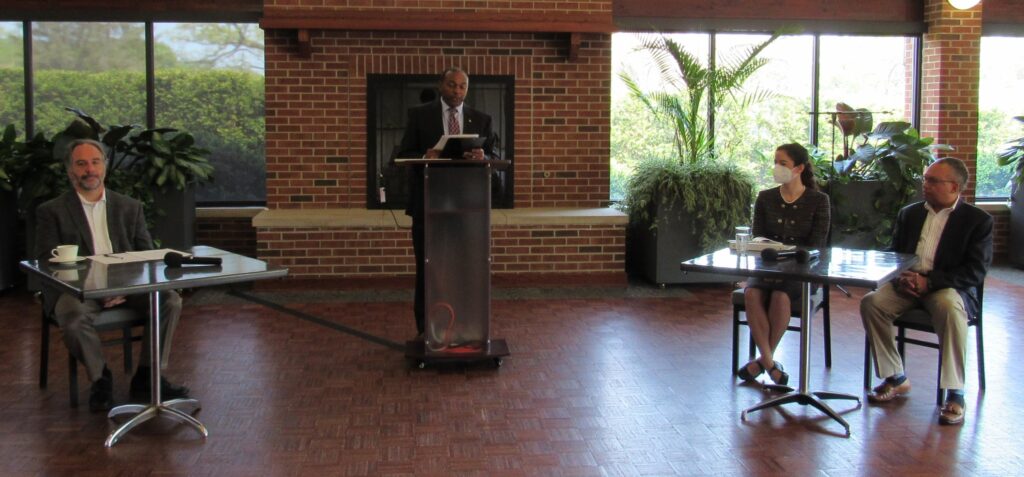

The Great War Symposium – Lesser-Known Stories of the Great War: Women, Minorities, Civilians, and the Untold was held at the First Division Museum at Cantigny Park in Wheaton, Illinois on 13 May 2022. The symposium featured opening remarks from Dr. Krewasky A. Salter, Executive Director, Museums at Cantigny Park; and Dr. Timothy Westcott, Director, George S. Robb Centre for the Study of the Great War at Park University.

Four sessions followed the opining remarks including “The Contributions of Women: Medicine and Communication,” “Native Americans and African Americans on the Battlefield,” “Women Casualties of War and as Forgotten Veterans,” and “Orphans of War and Precursors of LGBTQ+.” Each session was headed by a chair, including Dr. Krewasky Salter, Executive Director, Museums at Cantigny Park; Dr. Timothy Westcott, Director, George S. Robb Centre for the Study of the Great War at Park University; and Dr. Edward G. Lengel, Chief Historian, National Medal of Honor Museum, Arlington, Texas.

The inaugural Great War Institute Lecture Series focused on the life and service of Colonel Charles Young, (1864-1922).

Born to enslaved parents on 12 March, 1864 in May’s Lick, Kentucky, Charles Young was the third African American to graduate from the U.S. Military Academy West Point, first African American National Park Superintendent (Sequoia National Park, California), first Military Attaché to Haiti and the Dominical Republic, and first African American Colonel in the U.S. Army. The legacy of Colonel Young’s service in the Indian Wars, Spanish American War, Philippine American War, Pancho Villa Expedition and World War I are continued through the Charles Young Buffalo Soldiers National Monument in Wilberforce, Ohio, and collection held in the National Afro-American Museum and Cultural Center.

The Valor Medals Day Chat and Q&A session, held virtually, 26 March, 2021.

Hosted by Mrs. Jocelyn Hong; panelists include Mr. Daniel Dayton, Dr. Emma Jones-Lapsansky, Director Dr. Timothy Westcott, Associate Director Ashlyn Weber and Senior Military Analyst Joshua Weston.

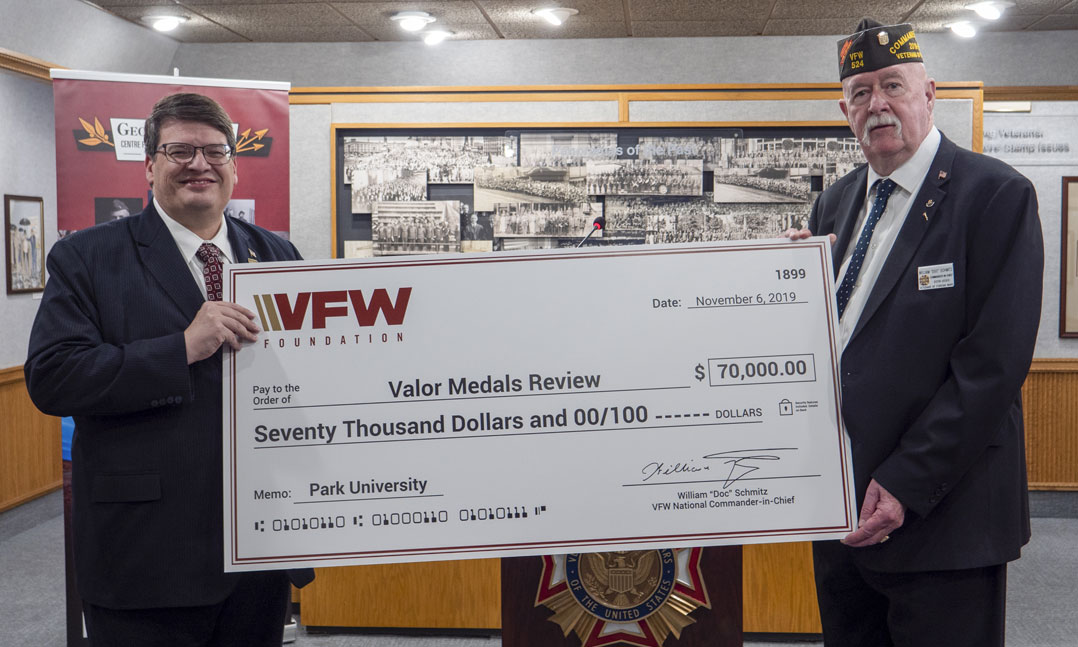

The World War I Valor Medals Review Panel, held at the National WWI Museum and Memorial, 19 June 2019.

Panelists include Director Dr. Timothy Westcott, Mrs. Bridget Locke, and Mrs. Kimberlee Ried.

Short Stories

From the retired RC Newsletter: The Valor Medals Review and the First Unknown

Originally Published: Fall 2020

Author: Ashlyn Weber

NOTE on Memorial Day 2021: On this Memorial Day one hundred years ago, Monday, 30 May 1921, four American servicemembers were exhumed from the Meuse-Argonne, Aisne-Maine, St. Mihiel, and Somme Cemeteries in France, and moved to the Chalons-en-Champagne City Hall for selection to become the first Unknown Soldier to be buried at the Memorial Amphitheater on 11 November 1921.

Sergeant Edward F. Younger, U.S. Army, was chosen to make the final selection, recalling,

“It was dim inside, the only light filtering in through small windows. For a moment I hesitated, and said a prayer, inaudible, inarticulate, yet real. Then I looked around. That scene will remain with me forever. Each casket was draped with a beautiful American flag. Never before had the flag seemed to have such sublime significance and beauty. About the walls were other flags, American and French; flower petals had been scattered over the floor, and outside I could hear the band playing a hymn…I was numb. I couldn’t choose. Then something drew me to the coffin second to my right on entering. I couldn’t take another step. It seemed as if God raised my hand and guided me as I placed the roses on that casket. This, then, was to be America’s Unknown Soldier, and by that simple act I had started him on his road to destiny.”

Lt. General James G. Harbord, U.S. Army, acted as an honorary pallbearer- present at the ceremony upon the Unknown’s return to the States for burial,

“We now worship at the altar of anonymity. Whether the Unknown Soldier sought the colors eagerly or was driven into it; whether he faced the front or the rear when death came to him, we cannot say; whether he was black, white, red, or yellow- for all those races fought under our flag- we shall never know. His tomb is a shrine on which flowers may be heaped without commitment.”

And President Harding, finally, spoke,

“He might have come from any one of millions of American homes. Some mother gave him in her love and tenderness, and, with him, her most cherished hopes. Hundreds of mothers are wondering today, finding a touch of solace in the possibility that the nation bows in grief over the body of one she bore to live and die, if need be, for the Republic.”

Original Article:

First Lieutenant George Seanor Robb returned to his home in Salina, Kansas at the end of the Great War in 1919 physically exhausted; recovering from four separate wounds incurred in combat in late September of 1918, he learned of his recommendation for the Medal of Honor whilst still in the hospital at Fort Riley. Even after the publishing of his official nomination, he resisted attending his own Medal of Honor ceremony in Topeka, requesting the medal be simply mailed to his address instead. Though 1Lt. Robb was by all means deserving of the honor, he, like many others in the same situation, seemed weary of the weight it brought in later years, not wanting to be seen as being any better than those they led into battle.

Nonetheless, two years later, George S. Robb was one of the 40-45 Medal of Honor recipients present to help escort the very first Unknown Soldier on the way to his final resting place at Arlington National Cemetery on 11 November 1921. At that same ceremony, thousands of civilians and retired military personnel flocked to watch the procession attended by then-President and First Lady Harding, John J. Pershing, Vice President Coolidge, Supreme Court Justices and President Wilson (via carriage) along with French and other foreign dignitaries, in the hopes of catching a glimpse at the casket that had just arrived home from France. It has only been in recent years that the identities of many individuals involved in the ceremony have become public knowledge, including the names of many honorary pallbearers, hidden purposefully at the time to give the impression that all who walked with the Unknown knew him in some form. The concealment of the identities of those who walked alongside in an Army, Navy, or Marine Corps uniform was not so much an effort to blur each of their stories and sacrifices, but to show to the crowd that everyone who served was to be equally represented. The man in the casket could have been anyone’s son, brother, husband, or father, and those in his procession would be no different; including the eight pallbearers who carried his body to the vault. Though their selection process is not yet fully known by the Robb Centre, the bearers represented each of the American Expeditionary Force’s core divisions; the United States Navy (through bearer James Delaney, Chief Gunner’s Mate; and Charles L. O’Connor, Chief Water Tender), United States Marine Corps (Ernest A. Janson, Gunnery Sergeant), United States Army (James W. Dell, Color Sergeant; Harry Taylor, First Sergeant; and Samuel Woodfill, Sergeant), United States Army’s Coast Artillery Corps (Louis Razga, First Sergeant) and United States Army’s Corps of Engineers (Thomas D. Saunders, Corporal). The last, Corporal T.D. Saunders, Cheyanne, American Indian, is one of the Valor Medals Review’s Native American individuals to be researched, walking in the same ceremony with half a dozen others confirmed by the George S. Robb Centre for the same process.

In this rare instance, the American veterans of World War I were no longer separated by branch, rank, or race, but were all responsible in escorting their brother to his place of burial, together. This, the first Tomb of the Unknown Soldier Ceremony and all who participated, is a direct representation of the George S. Robb Centre’s core assertion that there is no expiration on valor; regardless of background, everyone should be honored for their service.

Originally Published: September 2020

Author: Joshua Weston

The Meuse-Argonne Offensive, developed by the Allied commanders in Fall of 1918, established a final forced shift of momentum after a series of losses in the summer’s counteroffensives between the joined American, French, and British forces against Germany. The ultimate goal involved breaking the heavy German defensive Stellungs (positions) stretching along the Western Front, commonly known as the Hindenburg Line.

The offensive was planned in three phases. The first, beginning on 26 September, produced mixed results; various units of the Allied forces had great success in their advance, while others made no ground and took heavy losses. One of the most punishing of advancements during this phase included the Battle of Blanc Mont Ridge; due to its strategic significance as the highest point in the Champagne region, the Allied commanders knew the loss in territory would leave Germany with no easily defendable positions and strongholds, many of which they had held since the first Battle of the Marne in 1914. The second phase, beginning 4 October, consisted of providing replacements and relief for the initial assaulting units whilst continuing to instigate isolated hits. The third and final phase, beginning on 28 October, saw the clearing of remaining enemy units, such as in the Argonne Forest, and pursuing the German army during its retreat.

Conducted on notoriously deadly ground, the conditions of the Offensive were often uneven and riddled with open valleys, steep cliffs, and hills from which the Germans could observe up to 80 percent of the Allied advance without the need for the available reconnaissance balloons and aircraft. As a result, the Germans could easily conduct accurate and deadly machine-gun and artillery fire on the attacking units; from the heights of the Meuse River to the dense Argonne Forest, no Allied unit would easily march into German territory without heavy loss and exhaustion. Nevertheless, the Allies prevailed, and the Meuse-Argonne lasted until the signing of the armistice at 11:00 A.M. on 11 November 1918.

Originally Published: September 2020

Author: Logan Weist

The American First Army, from 16-19 September 1918, fought against Army Group Gallwitz, commanded by General Max von Gallwitz, southeast of Verdun in a sector on the front known as Saint Mihiel. The battle marked the first major independent American offensive of the Great War. General John J. Pershing had generally resisted British and French attempts to feed American troops into the font line as soon as they were available, instead preferring to concentrate American forces in a single army.

Pershing committed the 344th and 345th Battalions with 144 Renault FT-17 light tanks while the French 1st Assault Artillery Brigade with 275 Renault FT-17s. Schneider CA1 and Saint-Chamond tanks were supported by the II French Colonial Corps, IV Corps (1st, 2nd, and 89th Infantry Divisions) and V Corps (4th, 15th, and 26th) assaulted the West face of the salient. Outnumbered and caught by surprise, the German position collapsed. Records indicate that within a day and a half, American forces had captured approximately 13,000 German prisoners, and 466 German guns. German forces had 5,000 killed or wounded, while the Americans suffered 7,000 casualties.

The United States First Army secured its first major victory and provided to Britain and France that the American forces were capable of fighting German forces independently and not under British or French command. Military historian Edward G. Lengel noted that “By the end of the St. Mihiel Offensive…it was felt at last that the American units there on the front had developed into trained combat organizations.”

Originally Published: October 2020

Author: Timothy Westcott, PH.D.

The previous six months had brought land victories at Lexington, Concord, Boston, Fort Ticonderoga, and Bunker Hill. The Continental Army had proven its might, but there were no similar sea victories. The Second Continental Congress, meeting at the Pennsylvania State House (now Independence Hall), in Philadelphia, had earlier in the fall of 1775 appointed a committee to arrange a strategy for stopping vessels departing ports with stores and ammunition. Following debate, on 13 October, the Congress,

Resolved, That a swift sailing vessel, to carry ten carriage guns, and a proportionate number of swivels, with eighty me, be fitted, with all possible dispatch, for a cruise of three months, and that the commander be instructed to cruise eastward, for intercepting such transports as may be laden with warlike stores and other supplies for our enemies, and for such other purposes as the Congress shall direct.

Thus, was born the Continental Navy. However, the notion of continuing a permanent navy only lasted until August 1785, when the Congress of the Confederation sold the sole remaining ship. Nearly a decade later, with the passage of the Naval Act of 1794, was the current U.S. Navy established with the construction of six heavy frigates. Furthermore, not until 1972, under the leadership of Admiral Elmo Zumwalt, then Chief of Naval Operations, was the U.S. Navy authorized to celebrate its birthday on 13 October, coinciding with the resolution of the Second Continental Congress. Happy 245th Birthday to out U.S. Navy veterans and active duty sailors!

Commemorating the U.S. Navy’s birthday provides an opportunity to feature the first U.S. naval victory in the Great War. Following the Congressional declaration of war in April 1917, the USS Cassin (DD-43) was deployed to Queenstown, Ireland, to escort American troop convoys to ports in England and France. During routine escort service south of Mine Head Lighthouse, Monagoush, Ireland, on Monday, 15 October 1917, crew members sighted the German submarine U-61 and pursued. Early that afternoon, a torpedo struck the port stern of the Cassin. Standing on the port stern, Gunner’s Mate First Class Osmond Kelly Ingram (1887-1917) ran to the location that the Cassin stored her depth charges and began hurling them overboard. The torpedo struck above the waterline, igniting the depth charges, and flung Ingram overboard, killing him. The explosion injured nine other sailors, but no others were killed. Though Cassin‘s rudder had been blown off and stern extensively damaged, she circled. Approximately an hour after being struck, the Cassin‘s crew fired four rounds at U-61‘s conning tower, which discouraged her from further engagement.

Ingram was born in Oneonta, Alabama, and had served in the U.S. Navy just short of ten years when he became the Navy’s first enlisted sailor killed in World War I. He posthumously received the Medal of Honor; in 1919, the USS Osmond Ingram (DD-255) was named after him, representing the first Navy ship to be named for an enlisted sailor. He is buried at sea.

Originally Published: October 2020

Author: Joshua Weston

On 24 October 1917, the Kingdom of Italy and the Central Powers clashed in northeastern Italy at the battle of Caporetto, resulting in a decisive Central Power victory and a loss to the Italian army of 300,000 men. To regain morale, strengthen its units, and serve as proof of an American-Italian cooperation in the war effort, the Italian Ministry of War made a request to General John J. Pershing to send American troops to the Italian front. Pershing complied, and sent the 332nd Infantry Regiment, 82nd Division; upon arrival in France, the regiment learned they would not be fighting on the Western Front, but would be assigned to the Italian 31st Division.

Their first task came in early October of 1918 in staging a series of marches designed to deceive.

Each battalion, with different articles of clothing and equipment, would leave the city during daylight to be seen by Italian and Austro-Hungarian forces; they would then circle back, mostly at night, to pull of similar movements the next day. The appearance of a much larger unit quickly frightened the Austro-Hungarian forces and had begun reviving the much-needed morale in the Italian forces.

On 24 October 1918, the Italian Vittorio-Vento offensive had begun, and the 332nd Infantry, with the Italian 31st Division, stayed in reserve. The initial attack intended to attract Austrian reserves across the Piave River; although the Italians had a marked advantage in artillery, crossing the flooded river prevented two of the three central armies from advancing in unison, and the attack began to show signs of stalling.

After serving only three months in Italy, the 332nd saw its only action in the final hours, however, was able to take part in the last decisive movement, a sign of the end of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. After the signing of the Armistice in November, the 332nd Infantry remained in Italy until 3 April 1919 when the regiment embarked for the United States.

Originally Published: November 2020

Author: Ashlyn Weber

Members of the American Expeditionary Forces awoke on November 11, 1918, awaiting their orders along the French-Belgian-German lines of the Western Front, unaware that Allied and German staff members had spent the sunrise writing the final armistice arrangement in a train car outside of the Compiègne Forest. The initial draft, dated November 7, demanded nearly 35 separate conditions from the Allies- including the complete evacuation of German-controlled territories (many that had been held for nearly 50 years), the stripping of heavy artillery and armaments, and the forming of blockades to restrict the transport of supplies into Germany. Allowing for no alternate proposals, the German command staff had precious hours to concede, without doing so, extending a war they could not afford monetarily or physically- signing the final draft of armistice at 0500 hours French-time, November 11, with peace to return at 1100 hours.

An element of confusion remained as to how the Armies would behave in the mean-time; some commanding officers believed any losses within the morning would be a waste, others, that the German army would be shown no mercy until the very end. Skirmishes took place all along the Western Front, resulting in almost 3,000 Allied casualties within the last six-hour period, ending with the death of American Henry N. Gunther, the War’s final victim, at 10:59 a.m. Confusion, lack of communication, and a general heightened awareness of how impactful the final hours of War would be to the history books, pre-planned attacks remained on schedule, pushes to gain ground continued to act as the main objective, and commanding officers were left to their own devices. The issue was so predominant within Army staff that General Pershing was asked about the lack of coordination on Armistice day in front of the House of Representative’s Committee on Armed Forces in the fall of 1919, with the admittance of lackluster specification, “…we found out later that some of the more advanced detachments did not receive them (directions) in time, and continued the fighting after 11 o’clock” (Hearings before the Committee on Military Affairs. House of Representatives Sixty-Sixth Congress. First Session, Pgs. 1435-1508). In the following years, statements from personnel of nearly a dozen Army and Marine Corps divisions made similar complaints, disappointed in the lack of clarity from the Supreme Allied Commanders resulting in residual bitterness for years to come. The United States, though relieved of conflict for the next two decades, was not yet at peace with the incredible shock and loss that had been endured in such a short period of involvement.

Originally Published: November 2020

Author: Timothy Westcott, PH.D.

On Friday, 10 November 1775, the Second Continental Congress established the Continental Marine Corps, a set of troops “acquainted with maritime affairs as to be able to serve to advantage by sea when required”, independent from the Army, that could assist in disrupting British forces in Colonial waters. Since then, the Marines have boldly served in every American campaign, from the more famous encounters- taking the Castle of Chapultepec, Mexico City, Mexico, in 1847, to storming the Island of Iwo Jima, Japan, in 1945- to the lesser known- serving at the Battle of New Orleans in 1815, or at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, in 1898.

The Marines of World War I saw, perhaps, one of their defining moments in the ferocious assault on the German infantry in Belleau Woods, Hauts-de-France, June of 1918. Lasting 26 days, the 5th and 6th Marine Regiments were tasked with clearing the Woods, littered with stationary German machine gun nests, to slow the attempted progression of German troops across the Marne River. The conditions of battle quickly became dependent on fixed bayonet and close-quarter assaults as the Marines holding the wide grain fields just outside of the tree line were continuously hit with German waves exiting the Woods.

Under constant contact with enemy artillery and mustard gas, the Marines were successful in pushing back blocks of German divisions by late June, chasing the remaining companies from the Woods and recovering defensive lines that had been broken earlier in the month. 26 June 1918 marked the end of the most terrible battle the Marines had faced in their history, earning them two French Croix de Guerre with Fourragere, four individuals the Medal of Honor, and the legendary title of Teufelshunde- “Devil Dogs”- for their tenacity and incredible vigor.

The Robb Centre has the great honor of reviewing five veterans of the Marine Corps under the Valor Medals Review. This November, as we celebrate servicemembers of every generation, we wish all active and veteran members of the United States Marine Corps a Happy 245th Birthday!

Semper Fidelis to all of my Marine Corps brothers-in-arms.

Originally Published: December 2020

Author: Isabella Tasset

While the United States was doing what it could to address the logistical issues that arose from the aftermath of World War I, the soldiers left in Europe that December of 1918 had much to celebrate.

In France, people celebrated the armistice for weeks afterwards by setting off rockets, lighting bonfires, waving flags, dancing and singing both the French National Anthem and the Star-Spangled Banner. A soldier form Ohio, Charles A. Kline, writing to his parents in mid-November remarked, “…it seems very funny not to hear the big guns roaring and the almost constant glare of fire. But everybody is sure glad there are no more shells flying. I hope peace is soon signed and we are on our way home.” Kline would remain in Europe for the rest of the winter.

As the “Peace Christmas” approached, more celebrations were held across Europe, but most Americans were eager to return to their homes, “Father and Sisters, I have much to be very thankful for this Christmas Eve, altho (sic) many miles from home, I am quartered in a cozy little hut and well fed with plenty of the best of food, not out in the cold and wet trenches hungry like to many of us thought we would be only a few months back. And too, that I escaped the wounds and disease so many of our boys fell victim to this summer and fall, not saying anything about the unfortunate sons lying beneath the sod on these cruel and bloody battle fronts.”

At the same time that December 1918 was a time of celebration for American servicemembers, it was also one of solemn remembrance of those that didn’t make it to see peace restored. As winter progressed, Americans and Europeans alike began to experience the effects of shell shock in full force. The War had ended, but trauma lingered.

Originally Published: December 2020

Author: Timothy Westcott, PH.D.

The Christmas truce of 1914 remains one of the most recognizable events in the early months of World War I. The unofficial cease-fire along some lines of the Western Front brought the firing of rifles and shells of artillery to an eerie silence. The sounds of war were replaced with lighted Christmas trees, songs of the season, brass bands, the exchanging of cigarettes and plum puddings, and the famous soccer match.

German Lt. Kurt Zehmisch recalled, “How marvelously wonderful, yet how strange it was. The English officers felt the same way about it. Thus, Christmas, the celebration of Love, managed to bring mortal enemies together as friends for a time.” Officers from both sides disapproved and future attempts to repeat the celebration were forbidden by threatening disciplinary actions.

British Pvt. Frederick Heath, writing home, recalled, “Come out. English soldier; come out here to us. Up and down our line one heard the men answering that Christmas greeting from the enemy. How could we resist wishing each other a Merry Christmas? The night wore on to dawn- a night made easier by songs from the German trenches, the pipings of piccolos and from our broad lines laughter and Christmas carols. Not a shot was fired”.

In the spirit of the Christmas Truce, the George S. Robb Centre for the Study of the Great War team wished each of you a blessed holiday season.

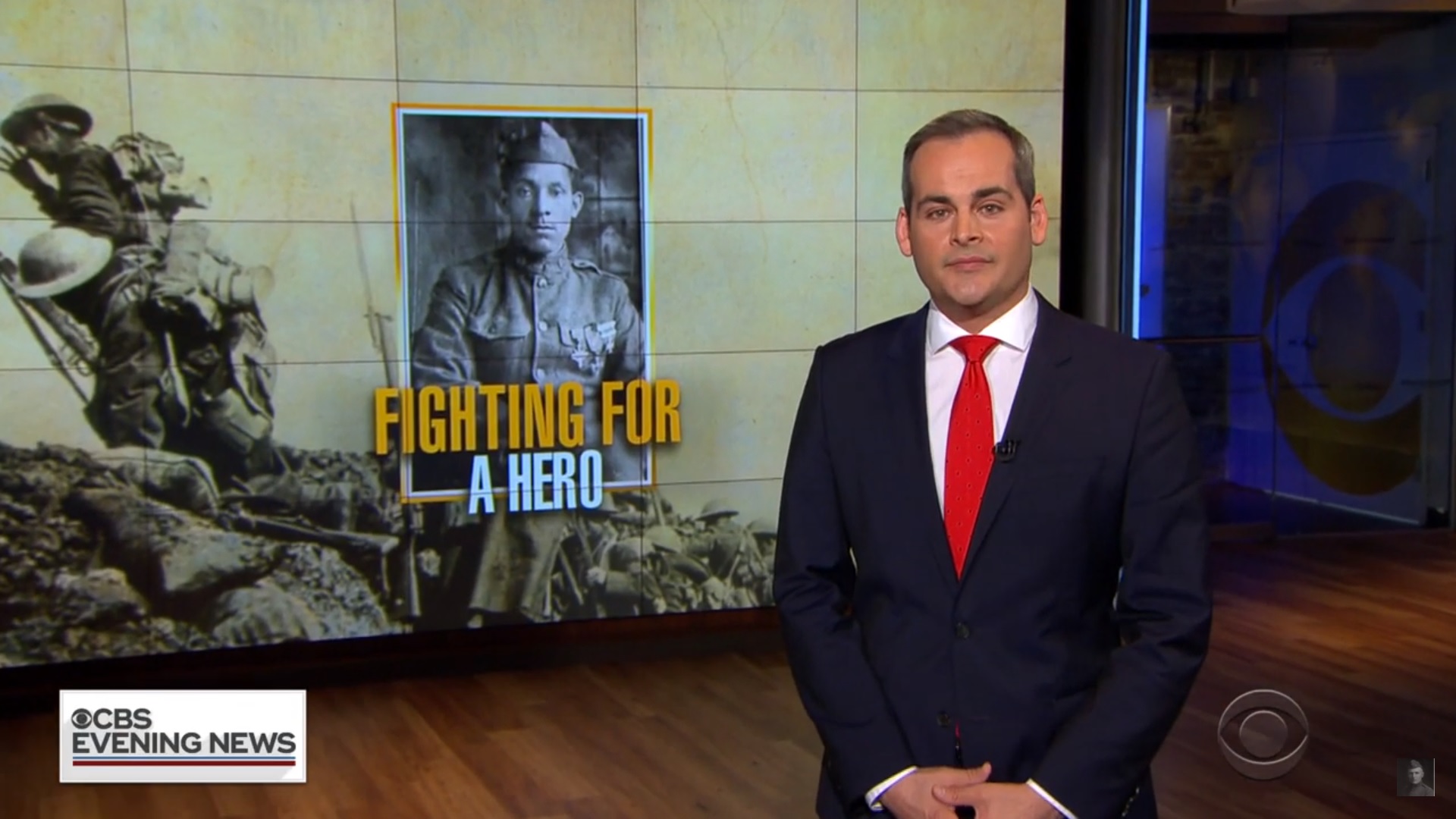

Media and Stories about the Robb Centre

Read, listen, and watch our local and national news coverage over the last several years.

Media