Aaron Richard Fisher

Aaron Richard Fisher’s Personal Narrative was derived from information found in public records, military personnel files, and local/state historical association materials. Please note that the Robb Centre never fully closes the book on our servicemembers; as new information becomes available, narratives will be updated to appropriately represent the life story of each veteran.

Please contact the Robb Centre for further clarification or questions regarding content or materials.

Military Honor(s):

Distinguished Service Cross 8 November 1918

Citation: The President of the United States of America, authorized by Act of Congress, July 9, 1918, takes pleasure in presenting the Distinguished Service Cross to Second Lieutenant (Infantry) Aaron R. Fisher, United States Army, for extraordinary heroism in action while serving with 366th Infantry Regiment, 92d Division, A.E.F., near Lesseux, France, 3 September 1918. Lieutenant Fisher showed exceptional bravery in action when his position was raided by a superior force of the enemy by directing his men and refusing to leave his position, although he was severely wounded. He and his men continued to fight the enemy until the latter were beaten off by counterattack.

Croix de Guerre with Silver Gilt Star 17 May 1919

Citation: An officer of admiral courage. Attacked by an enemy superior in number he displayed exceptional bravery in directing his men and in refusing to quit his post in spite of a serious wound. He remained with his men to fight until the enemy had been driven off by the counter attack. French Croix de Guerre with Gilt Star, under Order No. 17.470 “D”, dated May 17, 1919.

Purple Heart

Citation: Purple Heart awarded March 29, 1932, AG 201. Awarded for wound received in action September 3, 1919, then 2nd Lt. 366th Inf.

Life & Service

- Birth: 14 May 1895, Princeton, IN, United States

- Place of Residence: Lyles, IN, United States

- Race/Ethnicity: African American

- Death: 22 November 1985 Xenia, OH, United States

- Branch: Army

- Military Rank: Second Lieutenant

- Company:

- Infantry Regiment: 366th

- Division: 92nd

Aaron Richard Fisher was born on 14 May 1895 to Benjamin (1838-1924) and Macy Barnhill (1861-1902) in Princeton, Indiana. Benjamin (under alias Benjamin May), a farmer, had previously served as a Sergeant in Co. D., 100th US Colored Infantry, US Army, out of Kentucky during the Civil War.

Fisher worked on his father’s farm before enlisting (with parental permission) in the United States Army at Jefferson Barracks, Missouri on 28 February 1911. Fisher trained at Leon Springs, Texas and Camp Sherman, Ohio; he was initially assigned to Troop I, 9th Cavalry Regiment in Princeton, Indiana, before transferring to Co. F, 24th Infantry Regiment and serving in the Philippines. His rank changed as follows: Corporal on 13 September 1914, Sergeant on 31 December 1916, 1st Sergeant on 5 July 1917.

Fisher would also serve on the Mexican-American border and Pancho Villa Expedition in 1916. Fisher attended Officer Candidate School and received his appointment as 2nd Lieutenant, Infantry, on 1 June 1918 (depending on source: 25 July). Then-1st Lieutenant Fisher and other officer candidates of the 366th Infantry Regiment left Hoboken, New Jersey on June 15, 1918 on the U.S. Army Transport Ship Covington, arriving in Brest, France on June 21, 1918. Then-2nd Lieutenant Fisher received the Distinguished Service Cross, French Croix de Guerre with Gilt Star, and Purple Heart for his actions near Lesseux, France, on September 3, 1918;

“The President of the United States of America, authorized by Act of Congress, July 9, 1918, takes pleasure in presenting the Distinguished Service Cross to Second Lieutenant (Infantry) Aaron R. Fisher, United States Army, for extraordinary heroism in action while serving with 366th Infantry Regiment, 92d Division, A.E.F., near Lesseux, France, 3 September 1918. Lieutenant Fisher showed exceptional bravery in action when his position was raided by a superior force of the enemy by directing his men and refusing to leave his position, although he was severely wounded. He and his men continued to fight the enemy until the latter were beaten off by counterattack”.

Awarded DSC by CG, AEF, November 8, 1918. Published in G.O. No. 147, 1918.

“An officer of admiral courage. Attacked by an enemy superior in number he displayed exceptional bravery in directing his men and in refusing to quit his post in spite of a serious wound. He remained with his men to fight until the enemy had been driven off by the counter attack”.

French Croix de Guerre with Gilt Star, under Order No. 17.470 “D”, dated May 17, 1919. Date and place of act not shown.

Purple Heart awarded March 29, 1932, AG 201. Awarded for wound received in action September 3, 1919, then 2nd Lt. 366th Inf.

2nd Lieutenant Fisher and Co. E, 366th IR, left Brest, France on February 22, 1919 on the U.S. Army Transport Ship Aquitania, arriving in the United States February 28, 1919.

Serving admirably with the 366th Infantry Regiment, 183rd Infantry Brigade, 92nd Infantry Division, Second Lieutenant Aaron Fisher showed great courage and devotion to duty during a firefight near Lesseux, France, for which he was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, Purple Heart, and the French Croix de Guerre with Silver Gilt Star. This is his story.

Saint-Dié Sector – 3 September 1918

August 1918:

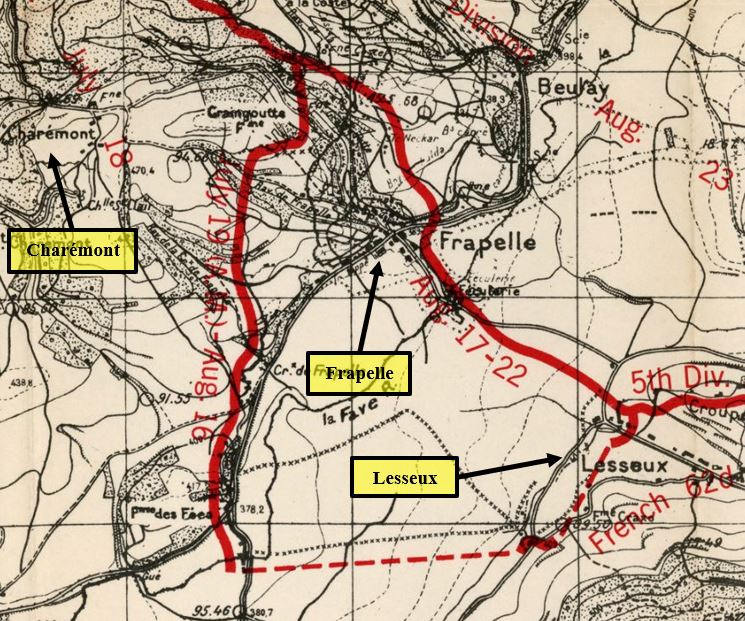

Following a handful of bloody clashes in the first months of the Great War, the naturally defensible terrain of France’s Vosges mountains made the undertaking of any significant offensive operations in this region virtually impossible. Thus, once the frontlines had settled and the spirit of élan that had carried the combatants through the opening weeks of the First World War calmed, the frontlines in this sector went almost entirely unchanged for the remainder of the war. The sector north of the city of Saint-Dié-des-Vosges in particular had developed a reputation as a relatively peaceful front, to which inexperienced or battle-weary divisions could be sent without fear of them being suddenly overrun. This arrangement changed on 17 August, 1918, when forces from the American 6th Infantry Regiment, 5th Infantry Division, suddenly descended from the mountains onto the occupied village of Frapelle.

The capture of Frapelle was of great strategic significance. In the years since the Saint-Dié Sector first settled up until its unexpected capture by the American troops, Frapelle had formed a deep wedge into the Allied lines, cutting-off communications between Allied forces at Charémont and Lesseux. Through its capture, the Allies were able to form a contiguous front across the Saint-Dié Sector, greatly increasing the efficiency of their defense. Further, Frapelle also controlled the southern end of the Saales Pass and one of the few major roads through the mountains. The concern that the Allies, having secured their own positions, might use this highway to strike at railway hubs in occupied Alsace-Lorraine worried German commanders greatly. Thus, the Germans concluded that they had to retaliate.

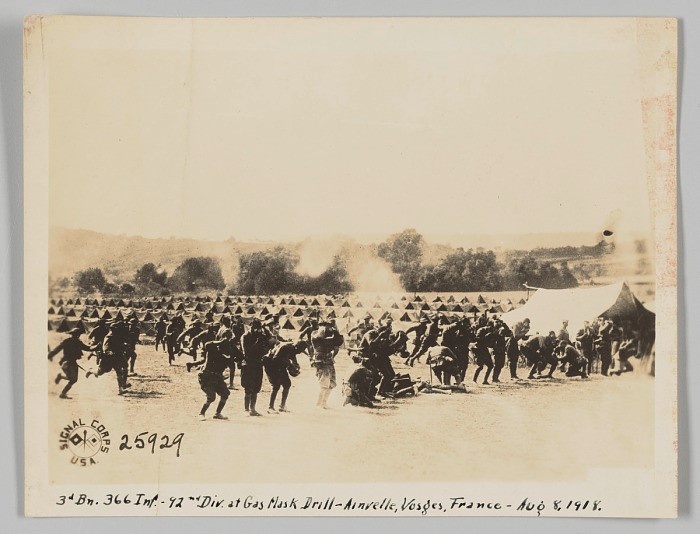

The 92nd Infantry Division received additional gasmask training during their time in the Saint-Dié Sector.

Mustering every gun in the sector, as well as heavy artillery and first-rate Prussian soldiers from another area, the Germans unleashed their fury onto the Allied lines. Shells rained down day and night, raiders attacked suddenly and without warning, and lethal gas attacks choked the life from any soldier caught without their gasmask. Additionally, German planes controlled the skies over Saint-Die and, when the weather permitted, rained down bombs and flechettes over their hapless victims. This onslaught would be the 92nd Division’s trial be fire.

On 22 August, just five days after the capture of Frapelle, the 92nd Infantry Division began its relief of the 5th Division in the Saint-Die sector. The following day, as the first elements of the 366th Infantry Regiment were moving to relieve the battered soldiers 6th Infantry Regiment at the frontline, the German guns opened fire on Frapelle, demolishing whatever was left of the town after 4 long years at the front. The 92nd Division suffered its first casualties from enemy fire during the barrage, including two killed and six more critically wounded. Regardless, the men of the 92nd Division quickly got to work developing the defensive positions around the towns of Lesseux and Frapelle, which the 5th Division had established before their relief. A week later, the men of the 92nd Division had almost adapted to life in the trenches, but the worst of the German assault was yet to come.

1-2 September 1918:

Whether it be from frustration at the dogged American defense or simply because their reinforcements had arrived, the severity of the Germans’ attacks greatly increased on the night of 31 August and the morning of 1 September. Mustard Gas filled the valleys of the Saales Pass and bright streaks of flame lit up the night as the Germans poured high explosives and liquid fire into the 92nd Division’s lines. However, the Allies held their lines and, with help from the French XXXIII Corps artillery, drove the Germans back. When the sun rose over the mountains, the carnage of the prior night’s battle became clear. German dead and wounded littered the pass, but the 92nd Division counted 4 dead and 34 gassed or wounded in their own lines. Among them was First Lieutenant Thomas Bullock of the 367th Infantry Regiment, the first officer of the 92nd Division to be killed in action.

3rd Battalion, 366th Infantry Regiment, 92nd Division at Gas Mask Drill in Ainville, Vosges, France, August 8, 1918.

As a result of the sheer amount of gas used by the Germans in the first days of September, 1918, the 92nd Division made a critical discovery. The standard issue Small Box Respirator (SBR) type gasmasks did not properly fit many of the men and, as a consequence, could not provide adequate protection from gas. To elaborate on this point, a common issue was that it was difficult if not outright impossible for some men to see through the SBR mask’s eyepieces. This made aimed fire virtually impossible if the mask was worn correctly, and as a result many men used only the mouthpiece of the mask, leaving their eyes and sometimes even their noses exposed to dangerous chemical agents. In the Saint-Dié Sector, this most often meant risking exposure to high concentrations of mustard gas, which could cause blindness or respiratory inflammation due to severe chemical burns. Further, as the availability of the improved Tissot type masks was still limited, they were only issued to those personnel deemed most important. This group did not include the enlisted men of the 92nd Infantry Division.

In the afternoon of 1 September a vicious firefight broke out on the slopes of Ormont, in the western region of the Saint-Dié Sector, following a devastating artillery barrage. However, the combined efforts of the 365th and 366th Infantry Regiments were once more able to prevent incursion into the Allied lines. That night, with the battle now in their hands, the 92nd Division sent patrols into no-man’s-land under the cover of darkness. However, when these parties entered the German lines, they found that the enemy had left their foremost trenches unguarded. This suggested that the Germans were anticipating an Allied counterattack, but the 92nd Division had no intention of obliging their opponent. Instead, though the German guns relentlessly pelted them with high-explosive and gas shells, the American troops spent the second day of September, 1918 repairing the damaged sections of their frontline.

3 September 1918:

Though their initial attacks had been repelled, the Germans were still eager to create a decisive resolution in the Saint-Dié Sector. Believing that the 92nd Division’s failure to counterattack was evidence of a timid disposition, the Germans sent out a series of raids to probe the 366th Infantry Regiment’s frontline for weaknesses. It was during one such attack that Second Lieutenant Aaron Fisher, an officer of the 366th Infantry Regiment, was critically wounded. However, though he stood bloodied in the face of the overwhelming foe, he did not falter. Even as his peers advised him to seek medical attention, Lieutenant Fisher held his ground against a numerically superior enemy and gave his men the inspiration that they needed to hold the line over the coming days. He remained at his post throughout the fight, retiring only once it was clear that the raiders had been repelled. Fortunately, Lieutenant Fisher survived this encounter and went on to have a long career as an officer in the United States Army.

For his bravery in the face of overwhelming odds, Aaron Fisher was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross under general orders No. 147 and the French Croix de Guerre with Silver Gilt Star. He was also awarded the Purple Heart on March 29, 1932, in recognition of the injuries that he sustained while leading his men.

Honorably Discharged on 17 March 1919, Fisher chose to reenlist under his pre-War rank, but was soon appointed to Warrant Officer (JG) in 1921. Fisher retired as Chief Warrant Officer in 1947, by then, he had served as chief clerk of bases not only in the continental United States, but in Hawaii and the Philippines as well.

During his service, Fisher led the formation of Wilberforce University’s Reserve Officer Training Corps, and was a faculty member of the University’s military science program. As a civilian, Fisher worked at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Greene Co., Ohio, and received the base’s very first 50-year service pin in 1961, retiring in 1965.

Fisher married Kinney T. Reed (1897-?) a schoolteacher, in 1925; he later married Mary Frances Myall (1905-1987) on 29 December 1951 in Greene, Ohio. Fisher died in Xenia, Greene Co., Ohio on 22 November 1985 at a long-term care facility, and is buried in Valley View Memorial Gardens in Xenia.