Ralph Ambrose O'Neill

Ralph Ambrose O’Neill’s Personal Narrative was derived from information found in public records, military personnel files, and local/state historical association materials. Please note that the Robb Centre never fully closes the book on our servicemembers; as new information becomes available, narratives will be updated to appropriately represent the life story of each veteran.

Please contact the Robb Centre for further clarification or questions regarding content or materials.

Military Honor(s):

Distinguished Service Cross

Citation: The President of the United States of America, authorized by Act of Congress, July 9, 1918, takes pleasure in presenting the Distinguished Service Cross to First Lieutenant (Air Service) Ralph Ambrose O'Neill, United States Army Air Service, for extraordinary heroism in action while serving with 147th Aero Squadron, 1st Pursuit Group, U.S. Army Air Service, A.E.F., near Chateau-Thierry, France, 2 July 1918. Lieutenant O'Neill and four other pilots attacked 12 enemy battle planes. In a violent battle within the enemy's lines they brought down three German planes, one of which was credited to Lieutenant O'Neill.

Distinguished Service Cross

Citation: The President of the United States of America, authorized by Act of Congress, July 9, 1918, takes pleasure in presenting a Bronze Oak Leaf Cluster in lieu of a Second Award of the Distinguished Service Cross to First Lieutenant (Air Service) Ralph Ambrose O'Neill, United States Army Air Service, for extraordinary heroism in action while serving with 147th Aero Squadron, 1st Pursuit Group, U.S. Army Air Service, A.E.F., near Chateau-Thierry, France: On 5 July 1918, First Lieutenant O'Neill led three other pilots in battle against eight German pursuit planes near Chateau-Thierry. He attacked the leader, opening fire at about 150 yards, and closing up to 30 yards range. After a quick and decisive fight the enemy aircraft fell in flames. He then turned on three other machines that were attacking him from the rear and brought one of them down. The other five enemy planes were driven away.

Distinguished Service Cross

Citation: The President of the United States of America, authorized by Act of Congress, July 9, 1918, takes pleasure in presenting a Second Bronze Oak Leaf Cluster in lieu of a Third Award of the Distinguished Service Cross to First Lieutenant (Air Service) Ralph Ambrose O'Neill, United States Army Air Service, for extraordinary heroism in action while serving with 147th Aero Squadron, 1st Pursuit Group, U.S. Army Air Service, A.E.F., near Fresnes, France, 24 July 1918: Lieutenant O'Neill, with four other pilots, engaged 12 enemy planes discovered hiding in the sun. Leading the way to an advantageous position by a series of bold and skillful maneuvers. Lieutenant O'Neill shot down the leader of the hostile formation. The other German planes then closed in on him, but he climbed to a position of vantage above them and returned to the fight and drove down another plane. In this encounter he not only defeated his opponents in spite of overwhelming odds against him, but also enabled the reconnaissance plane to carry on its work unmolested.

Croix de Guerre with Bronze Palm

Life & Service

- Birth: 7 December 1896, Durango, Mexico

- Place of Residence:

- Race/Ethnicity: Hispanic American

- Death: 23 October 1980 Redwood City, CA, United States

- Branch: Army Air Corps

- Military Rank: First Lieutenant

- Company:

- Infantry Regiment: 147th Aero Squadron

- Division: 1st Pursuit Group

Ralph Ambrose O’Neill was born to Ralph Lawrence (1859-1939) and Dolores Petra Avila y Landa (1868-1919) in his mother’s hometown of Durango, Mexico, on 7 December 1896. Ralph was the fifth of eight children; Alicia (1887-1927), Louise (1890-1988), Esther (1892-1971), Carmen (1895-1978), Frances (1898-1962) and Guadalupe (1900-1985) were all born in Durango; the last child, Howard (1904-1979) was born in Cananea. O’Neill’s father, Ralph Lawrence, was an Irish-American banker and businessman, who expanded his trade to newspapers and local politics in the years leading up to the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920).

The family relocated to El Paso, Texas, where O’Neill and his siblings attended El Paso High School; O’Neill became a member of the football, baseball, and debate teams, graduating in 1914. The O’Neills returned to Mexico in the mid-1910s, and settled in Nogales, where O’Neill worked for a mining company; in 1916, he began attending Lehigh University, a private research institution, in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania.

“Through a wild series of fortunate coincidences, there came a chance to get into a mining operation of my own. My father’s bank staked me enough money to buy in as a partner. I threw myself into the new venture, worked my tail off, and in six months had cleared $25,000- a sizable chunk of cash for a kid of nineteen. I used part of the money to finance a crash course in advanced mining engineering at Lehigh University, where I was accepted as a special student because of my previous tutoring and on-the-job experience in mining.”

O’Neill applied for, and was accepted, into the U.S. Army Signal Corps in the Fall of 1917, and began his training at Princeton University’s School of Military Aeronautics, where he took courses such as, “Aeronautical Motors,” “Theory of Flight,” “Cross Country and General Flying,” “Aerial Observation,” “Gunnery,” “Signaling and Radio,” “Infantry Drill” and “Calisthenics”, graduating in November. O’Neill then attended training at Hicks Field #1, Camp Taliaferro, Fort Worth, Texas, at the time, controlled by the Royal Flying Corps, and later, Army Air Service.

O’Neill completed his training by the end of the year, and was stationed at Mitchel Field (Mitchel Air Force Base); after hopping between Canadian (Canadian Royal Flying Corps) and American Training Squadrons, O’Neill was finally assigned to the 147th Aero Squadron, and sent overseas on 7 March 1918 as a Second Lieutenant. After arriving in England in mid-March, O’Neill did not officially re-join his command until mid-April. The 147th continued their training well to the end of the month, working specifically with French Nieuport 28s, until being called to the front and stationed at the Toul-Croix de Metz Aerodrome with the rest of the 1st, 2nd, and 4th Pursuit Groups, I and IV Corps Observation Groups, and assorted Balloon and Photographic Companies, on 1 June, 1918. For the remainder of the month, 2 Lt. O’Neill made nearly thirteen patrols in the Toul Sector, but did not participate in any major enemy skirmishes.

The 147th moved to the Marne Sector at the first of the month and were stationed at Saints Aerodrome in Saints, France from 9 July to 1 September with the 27th, 94th, and 95th Aero Squadrons. It was in this region that 2nd Lt. O’Neill received the Distinguished Service Cross for actions on 2 July over Chateau-Thierry; the Bronze Oak Leaf Cluster (in lieu of second DSC) for actions on 5 July over Chateau-Thierry; Second Bronze Oak Leaf Cluster (in lieu of third DSC) for actions on 24 July over Fresnes, and Croix de Guerre with Bronze Palm for and unspecified date and action. Because 2nd Lt. O’Neill qualified several times over for the Valor Medals Review, the Robb Centre has selected his first Distinguished Service Cross as the focus of his investigation.

2nd Lt. O’Neill’s first four victories on 2, 5, and (2) 24 July were shared with other airmen, as was his last on 10 October aboard a SPAD XIII over Bantheville, France, for a total of 5, ranking him behind notable airmen Eddie Rickenbacker (26 victories) and Jacques Michael Swaab (10 victories).

In early September, the 147th moved again to the Orly Air Base, Paris, France to begin exchanging their Nieuport 28s to SPAD S.XIIIs, then, stationed at Rembercourt Aerodrome in Rembercourt-Sommaisne, France with the 1st Pursuit Group. The 147th flew missions in support of the St. Mihiel and Meuse Argonne Offensives between September and late October. On 29 November, O’Neill was promoted to 1st Lieutenant; he and the 147th were moved to the Colombey-les-Belles support Aerodrome and re-designated 1st Air Depot on 12 December. 1st Lt. O’Neill returned to the United States aboard the U.S. Army Transport Ship Canopic on 19 February 1919 and was Honorably Discharged on 21 April.

“O’Neill was given the nickname “The Snake” for his unorthodox flying techniques, and fierce aggression in seemingly unfavorable odds. He was amongst the first combat pilots to paint the now infamous “Sharks Teeth” nose art in order to strike fear into the enemy. After gaining notoriety, he was also said to go into battle sitting on a large frying pan, which subsequently saved his life from machine gun fire.”

First Lieutenant Ralph Ambrose O’Neill served in the United States Army Air Corps with the 147th Aero Squadron, 1st Pursuit Group during his act of valor on 2 July 1918.

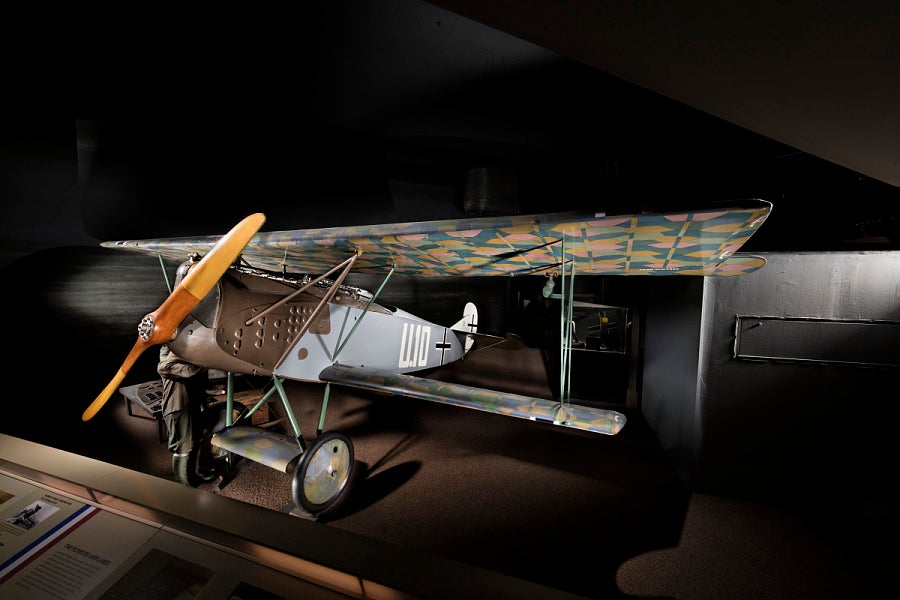

Fokker D.VII at the Smithsonian Institution National Air and Space Museum. May 2, 2016. Photo by Eric Long.

The troops in the area of Chateau-Thierry frequently saw planes overhead as they moaned and maneuvered in a cumbersome manner across the sky. Planes were a newly introduced technology in the great war, with the Wright brothers first flight at Kitty Hawk occurring only 11 years before the war broke out. Planes were originally used to scout, but quickly adapted to a combative role against ground and air targets, as armies waged bloody battle to gain ground the 1st Pursuit Group fought tooth-and-nail for the skies.

The Germans in this sector were highly aggressive, and well-armed; a far cry from the amateur pilots that the Americans encountered in the Toul Sector far to the east in the months prior. Although the Germans had prove their reluctance to attack Allied formations over Toul, in the skies over Chateau-Thierry, located in the gap between the Aisne and Marne rivers, the Americans soon found themselves encountering much more hostile formations of a dozen and highly aggressive Germans flying their celebrated Fokker D. VII scout planes. As a result, the American aviators were forced to either adapt or die.

A Pursuit tactic that emerged in response to the Germans’ overwhelming show of force in having a squadron of planes flying in formation as a second group, known as a Pursuit Group, flew far overhead as a supporting element. The Pursuit Group would be commanded by a pursuit pilot who would have a broad view over everything below him. Given their position, the pursuit pilot and his group of five to six planes would be able to enter a powered dive to deliver unexpected blows on enemy planes. It was in this commanding position that 2nd Lieutenant Ralph O’Neill found himself on 2 July 1918.

-2 July 1918-

Piloting the rugged Nieuport 28 scout planes, Lieutenant O’Neill and 8 other members of the 147th Aero Squadron soared high over the battlefield. The main squadron below consisted of five members of ‘C Flight’ while Lieutenant O’Neill led the ‘B Flight’ consisting of four fighters. As the American formation flew above friendly skies, Lieutenant O’Neill spotted a lone scout flying below them, however, given Lieutenant O’Neill’s high altitude the plane was too low to identify as friend or foe. Lieutenant O’Neill and ‘B Flight’ turned their planes into a dive towards the unknown aircraft and separated themselves from ‘C Flight.’ Lieutenant O’Neill and ‘B Flight’ saw that the lonely scout aircraft was a friendly French pilot who had likely become separated from his squadron, subsequently, Lieutenant O’Neill waved the French pilot to join his group, and they setout to rejoin ‘C Flight.’

A few minutes after adopting the French pilot, Lieutenant O’Neill spotted another contact formation of particularly large planes that were slowly moving between O’Neill’s squadron and the clouds. Lieutenant O’Neill moved toward the group to assess the situation and as he approached he spotted the red, blue, and white roundel on the wing of one, indicating that the group was friendly.

By this time, however, Lieutenant O’Neill realized that he had completely lost track of ‘C Flight’ and to exacerbate the situation, two members of his own formation had disappeared following the last encounter, leaving him with only three planes including his own. As the small group flew at a high altitude, they spotted a squadron of five planes moving below. Lieutenant O’Neill entered into his third dive of the day to pursue potential enemy planes, this time he spotted a mottled paintjob of a leading plane with black and white stripes and red tail. Lieutenant O’Neill and his small group watched the unidentified formation scatter and a thin black iron cross on the lead plane’s wing had appeared, the planes were confirmed to be German.

Lieutenant O’Neill and his small group entered into a lethal dive towards the Germans with Lieutenant O’Neill pursuing the lead German fighter plane as his target. As the other planes of his small group dove, Lieutenant O’Neill chased the fighter, following him closely behind its tail. The German pilot pulled upward to outmaneuver Lieutenant O’Neill and his comrades and O’Neill let out a stream of machine-gun fire which tore through the German’s fuselage and wings. Though the affair had only lasted a few seconds, O’Neill was nearly upon his enemy by the time its nose turned from its dive. With barely enough time to avoid colliding into the ruined German plane, O’Neill followed it down, firing one final burst of machine-gun fire on the falling German aircraft.

After having descended nearly two miles in his pursuit of the German lead fighter plane, Lieutenant O’Neill’s guns unexpectedly jammed. It was only then, without the deafening sound of his own guns, that he heard the two enemy planes following close on his own tail. Lieutenant O’Neill quickly moved to evade the German machine-guns, however, he had less than a mile of sky left between him and the ground. Regardless, he would have to think quickly if he was going to survive.

Lieutenant O’Neill kept his wits and made a break for the frontlines. He had hoped that the Allied antiaircraft guns or intervention of friendly planes would shake his pursuers. However, as O’Neill began to pull up to avoid hitting the ground, he rapidly lost speed; if he lost too much, his plane would no longer be able to generate enough lift to keep itself in the air. Fortunately this worked to his advantage as the Germans, who were likely experiencing a similar slowing, pulled up less sharply than he did and flew past him. O’Neill would later remark that they were fortunate that his own guns were jammed, else they would have been his second and third victims of the day.

2nd Lieutenant Ralph A. O’Neill sitting on the fuselage of his Nieuport 28. Photo Courtesy of USAF National Museum.

Second Lieutenant O’Neill received the Distinguished Service Cross for his heroism on 2 July 1918, under General Orders 116 (1919) of the United States War Department.

While overseas, O’Neill met Englishwoman Priscilla Eileen Wilson (1891-1954), and married her, on 31 January in St. Martin, London, England- she followed, on steamship, and the couple moved to San Francisco, California.

O’Neill, in the early 1920s, was approached by then-Governor of Sonora, Adolfo de la Huerta (later President of Mexico), to assist with the formation of the Mexican Air Service; O’Neill was swiftly named Chief of the Mexican Air Force, serving in that role until 1925.

“He trained six air squadrons and helped set up the first commercial airline for the government of President Alvaro Obregon. In 1924 he commanded an air squadron in an unsuccessful rebellion led by Adolfo de la Huerta.”

By the late 1920s, O’Neill had interacted with several early American commercial airline companies in an attempt to create an independent airline company with concentration in South America. A partnership with Consolidated Airlines culminated in the founding of the New York, Rio, Buenos Aires Line, (NYRBA) which ran from 1929 to its merging with Pan American Airlines in 1930.

“Mr. O’Neill’s airline was purchased in 1930 by Pan Am for $4 million, creating what was then the largest fleet of big airplanes anywhere, and establishing United States dominance in aviation in Central and South America.”

O’Neill was not out of a job for long- he founded the Bol-Inca Mining Corporation, a company tasked with the transportation of materials via air over the Andes Mountains, based in Nevada. O’Neill and his wife divorced in 1937; in November of the same year, O’Neill married Jane Elizabeth Galbraith (1905-1997) in Stamford, Connecticut. Galbraith and O’Neill had not only been acquainted for several years, but worked together during early NYRBA Sikorsky S-38 test flights;

“One of Jane’s duties was to keep the flight log…became lyrical about the beauty of the Flordia gulf coast from the vantage point of low altitude…there is less poetry in her account of the violent squalls, thunder, and lightning we encountered on the Cuban coast.”

The O’Neills had two children, Patricia Jane (1938-) and Louise Elizabeth (1940-2015) in New York, NY and Englewood, New Jersey. O’Neill retired in the 1960s, and the family settled in California. O’Neill died on 23 October 1980; he is buried in Menlo Park, San Mateo County, California.