William Branch Crawford

William Branch Crawford’s Personal Narrative was derived from information found in public records, military personnel files, and local/state historical association materials. Please note that the Robb Centre never fully closes the book on our servicemembers; as new information becomes available, narratives will be updated to appropriately represent the life story of each veteran.

Please contact the Robb Centre for further clarification or questions regarding content or materials.

Military Honor(s):

Distinguished Service Cross

Citation: The President of the United States of America, authorized by Act of Congress, July 9, 1918, takes pleasure in presenting the Distinguished Service Cross to Captain (Infantry) William B. Crawford, United States Army, for extraordinary heroism in action while serving with 370th Infantry Regiment, 93d Division, A.E.F., at Ferme-de-la-Riviere, France, 30 September 1918. Having been placed in command of Company L, whose task it was to lead the advance in an attack, the same undertaking having failed the day previous, Captain Crawford, in order to assure the success of the attack, personally led the advanced element of his company in the face of heavy fire. The objective was successfully carried, due to Captain Crawford's gallant conduct.

Life & Service

- Birth: 19 August 1878, Corinth, MS, United States

- Place of Residence:

- Race/Ethnicity: African American

- Death: 4 March 1938 Chicago, IL, United States

- Branch: Army

- Military Rank: Captain

- Company: [L]

- Infantry Regiment: 370th

- Division: 93rd

William Branch Crawford was born to Sampson (?-?) and Elizabeth Rogan (?-?) on 19 August 1878, in Corinth, Mississippi.

Crawford enlisted in the U.S. Army’s Co. L, 24th Infantry Regiment as a Sergeant on 1 November 1898, discharged 31 October, 1901; enlisted 1 November 1901, discharged 31 October 1904; enlisted 1 November 1904, discharged 23 December 1907; enlisted 23 April 1908, discharged 22 April 1911; enlisted 23 April 1911, discharged 22 April 1914; enlisted 23 April 1914, discharged 7 July 1916; enlisted 5 October 1916.

Appointed Captain of the 25th Infantry Regiment 5 July 1917.

Captain Crawford and his Company sailed on the U.S. Army Transport Ship President Grant, on 7 April 1918, arriving in Brest, France on 13 April. Captain Crawford received the Distinguished Service Cross for his actions at Ferme-de-la Riviere, France, on 30 September 1918.

“The President of the United States of America, authorized by Act of Congress, July 9, 1918, takes pleasure in presenting the Distinguished Service Cross to Captain (Infantry) William B. Crawford, United States Army, for extraordinary heroism in action while serving with 370th Infantry Regiment, 93d Division, A.E.F., at Ferme-de-la-Riviere, France, 30 September 1918. Having been placed in command of Company L, whose task it was to lead the advance in an attack, the same undertaking having failed the day previous, Captain Crawford, in order to assure the success of the attack, personally led the advanced element of his company in the face of heavy fire. The objective was successfully carried, due to Captain Crawford’s gallant conduct”.

Captain William Branch Crawford commanded Company [L], 370th Infantry Regiment, under the command of the French 59th Division. During his time in command, he was able to distinguish himself despite facing blatant discrimination from his commanding officers. This is his story.

Ferme de la Riviere – 30 September

28 September, 1918:

By September 1918 the German Army had been all-but totally exhausted. The German Spring Offensive earlier that year had not only failed to produce a decisive result, but had exhausted the Germans’ resources and manpower. The Allies, on the other hand, were producing decisive results on the Western Front. Now reinforced by some 2 million American Doughboys and a promise of more on the way, the Allied forces began a series of campaigns in August 1918 that the undersupplied, demoralized, and oftentimes starving German Army was unable to withstand. Across nearly 100 days of ceaseless offensives spanning virtually the entire Western Front, one of the most decisive campaigns was the Franco-American Meuse-Argonne Offensive, begun on 26 September, 1918. However, while the overwhelming majority of American forces engaged on 28 September were somewhere on the long Meuse-Argonne Front, the 93rd Division was not among them.

This was in part due to the fact that the 93rd Division was never brought to the strength of a full division. Lacking vital supporting units, such as the Divisional Field Artillery Brigade and Supply Trains, it would have been virtually impossible for the 93rd Division to undertake independent operations. Rather than using white support troops to bring the 93rd Division up to strength or integrating the organized Infantry Regiments of the 93rd Division into American Divisions, the commanders of the AEF instead chose to loan their understrength African-American Division to the French. Unlike their American counterparts, the French had few qualms with sending non-white soldiers to die in their place.

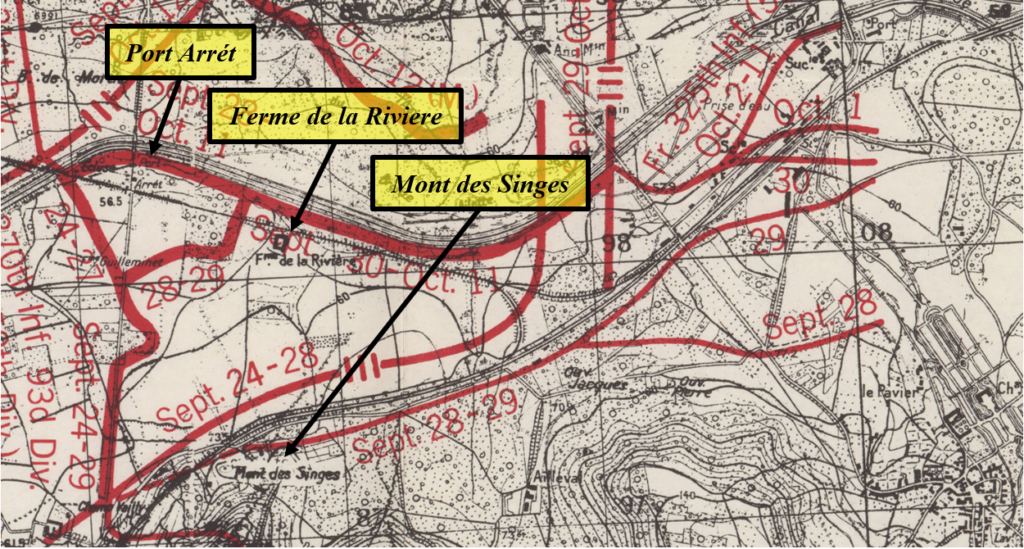

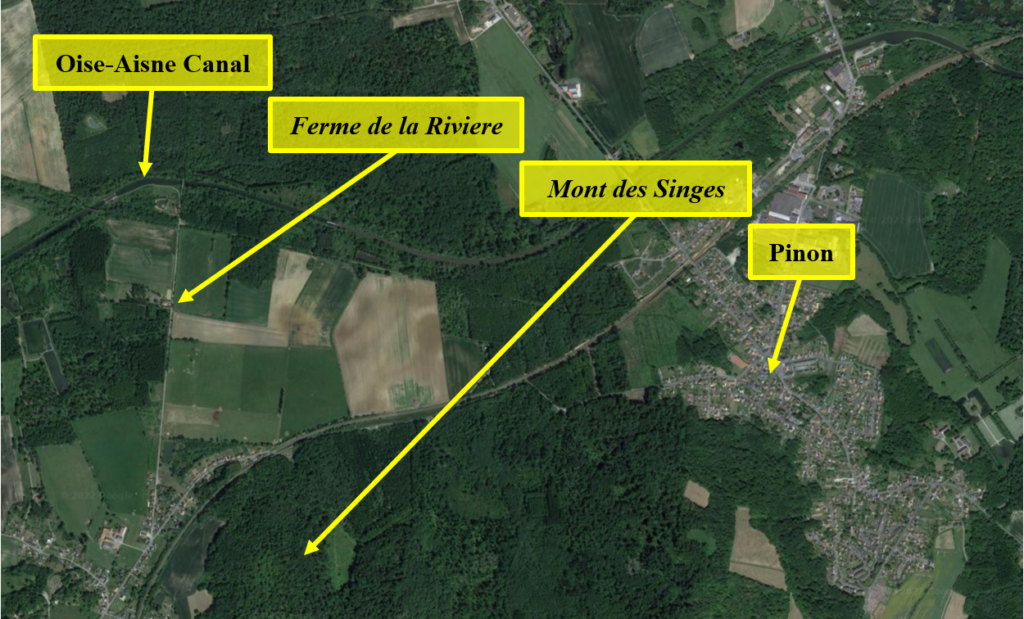

That was exactly what the 370th Infantry Regiment was doing on 28 September, 1918. Split-off from the rest of the 93rd Division and placed at the disposal of the French 59th Division, French XXX Corps, French 10th Army, the 370th Infantry Regiment held a section of the French frontline situated directly on the south bank of the Oise-Aisne Canal. Opposite them, the forces of the German Seventh Army had been given orders to withdraw to a stronger defensive position on the other side of the canal due to manpower shortages caused by the ongoing Meuse-Argonne offensive to the East. This movement was undertaken on the night of 27/28 September, after which the majority of Germans moved north of the canal. All that was left to the south were a handful of holdouts and bastions, the purpose of which was to delay French pursuit long enough for the rest of the German Army to establish itself to the north. The French, naturally, hoped to exploit this momentary weakness in the German lines, and sent out orders for the 59th Division, 370th Regiment attached, to pursue their foe.

As the unit currently stationed on the 59th Division’s boundary with the Canal, the 370th Infantry Regiment was given the unenviable task of advancing up the open ground of the Ailette river valley (through which the Oise-Aisne Canal flows) in clear view of the German guns in the Bois de Mortier on the other bank. German holdouts on the southern bank, particularly atop Mont des Singes and in the woods around the Ferme de Riviere, could also use natural caves and an expansive tunnel network to strike Allied forces when and where they least expected. In light of this danger, the 370th Infantry Regiment was ordered to delay its attack until 2100 Hours (9:00 PM), by which point the dark of night would conceal their advance. However, the Regimental Commander of the 370th Infantry Regiment, Colonel Thomas A. Roberts, apparently fudged these orders. Instead, he ordered his men to begin their advance over open ground at 0900 Hours (9:00 AM), in clear view of the Germans’ machine-guns and artillery observers. The results of this mistake were devastating; the entirety of 3rd Battalion (including Captain William Crawford’s [L] Company) was caught in the open by German artillery fire and pinned there until Colonel Roberts was able to secure counterbattery fire from the French. By the time that the French shells began to fly down-range, nearly a hundred men and officers had been wounded or killed by the German bombardment. Colonel Roberts was able to have this error dismissed as a mistake, but according to the 370th Regiment’s Chaplain this “mistake” was a deliberate choice made by a commanding officer who had no regard for his own men. Though the assaulting elements of the 370th Infantry Regiment had paid a heavy price, they were ultimately able to secure a small wood on the South bank of the Oise-Aisne Canal, which controlled the crossing at Port Arrét.

29 September, 1918:

Elsewhere on the 59th Division’s front, the French had made substantial progress. Fortified hilltops, such as Mont des Singes and Hill 158, which had once hindered their advance, were left virtually abandoned by the fleeing Germans and were quickly captured. Further, advancing through ruined woods and hills, the French had ample cover from German guns north of the Oise-Aisne Canal. Virtually all German holdouts south of the canal were rooted out by veteran French infantrymen and French tanks, though the latter retired on 29 September due to heavy casualties. But, like the 370th Infantry Regiment, the French advance also slowed upon approaching the Oise-Aisne Canal, where open ground on either side of the waterway left them open to attack. Consequently, the 59th Division’s offensive, including that of the 370th Regiment, made little gains on 29 September.

As the men of the 370th Regiment struggled to take the field, another struggle was occurring among its officers. Though Colonel Roberts had long wished to replace his black officers with white ones, General Vincendon, commanding officer of the French 59th Division, had been largely ambivalent to these requests. However, following the disastrous advance of 3rd Battalion, 370th Infantry Regiment, on 28 September, Colonel Roberts was able to shift the blame from himself to Lieutenant-Colonel Otis B. Duncan who, aside from being one of the highest-ranking African-Americans in the United States Army at the time, had led the attack. Citing Duncan’s supposed failure as evidence of incompetence and cowardice among his black officers, Colonel Roberts was able to persuade General Vincendon to heed his request for white officers. Naturally, rumors that the 370th Regiment’s black officers were bound for the chopping block began to spread through the ranks, though it would take some time for the concerns raised by such murmuring to be realized. Nevertheless, such gossip had something of a chilling effect between the Battalion Commanders of the 370th Infantry Regiment and Colonel Roberts.

30 September

On 30 September, the German opposition facing the 59th Division began to give-way. As the French components of the Division launched assaults on German bastions around Pinon, Lieutenant-Colonel Duncan’s 3rd Battalion moved back to the 370th Regiment’s front. Though their attack two days prior had failed, the German opposition had grown weaker in that time and the wooded area held by Company [F], 2nd Battalion, gave 3rd Battalion a strong jumping-off point for an operation to claim Ferme de Riviere, which was the last significant German holdout in the 370th Regiment’s sector. Knowing that his career was likely riding on the success of this attack, Lieutenant-Colonel Duncan entrusted the leading role to Captain William Crawford, the commanding officer of Company [L]. Representing some of the most experienced soldiers in the entire regiment, Captain Crawford and his men were an excellent choice to lead this attack.

About 0300 hours the signal to advance came and [L] Company burst from their lines. Advancing across open ground under a hailstorm of shrapnel and bullets, the men of Company [L] quickly seized Ferme de la Riviere, with Captain Crawford personally leading the charge. Due to this outstanding demonstration of courage and leadership – a far cry from the cowardice and incompetence which Colonel Roberts had claimed was rife in his African-American officers – the 370th Regiment was able to drive the Germans from not just Ferme de la Riviere, but entirely out of their sector and across the Oise-Aisne Canal as well.

For this exemplary show of courage, Captain William B. Crawford was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross in 1919 under General Orders No. 46.

Capt Crawford was discharged 14 July 1919; enlisted 15 July 1919, discharged 14 July 1922 as a Technical Sergeant for Headquarters Co., 25th Infantry Regiment. Last enlistment was on 15 July 1922, retired from the U.S. Army as a Master Sergeant of the Service Company, 25th Infantry Regiment, on 13 January 1925.

Crawford married Roberta Dodd (1897-1954) on 22 December 1917, they divorced in the late 1920s; he never remarried or had children. After his retirement from the Army, Crawford lived in Chicago, Illinois. Crawford died of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy on 4 March 1938 at Cook County Hospital in Chicago, Illinois.