Tom Rivers

Military Honor(s):

Distinguished Service Cross 11 December 1918

Citation: The President of the United States of America, authorized by Act of Congress, July 9, 1918, takes pleasure in presenting the Distinguished Service Cross to Private Tom Rivers (ASN: 2169507), United States Army, for extraordinary heroism in action while serving with Company G, 366th Infantry Regiment, 92d Division, A.E.F., near the Bois-de-la-Voivrotte, France, 11 November 1918. Private Rivers, although gassed, volunteered and carried important messages through heavy barrages to the support companies. He refused first aid until his company was relieved.

Life & Service

- Birth: 6 January 1894, New Castle, AL, United States

- Place of Residence:

- Race/Ethnicity: African American

- Death: 14 June 1977 , United States

- Branch: Army

- Military Rank: Private

- Company: [G]

- Infantry Regiment: 366th

- Division: 92nd

Private Tom Rivers Served in Company [G], 366th Infantry Regiment, 183rd Infantry Brigade, 92nd Division. At the time of his act of valor, his unit was a part of VI Corps, American Second Army. This is his story.

Marbache Sector – 11 November

9 November, 1918

General Ferdinand Foch and General John J. Pershing at the latter’s quarters, Val des Ecoliers, Chaumont, France. Photograph taken by Cpl. Jack Abbot, US Army Signal Corps, June 17, 1918. Photograph from the National Archives.

On 9 November, 1918, the Commander of the Allied Forces, French Marshal Ferdinand Foch, gave orders that, while long-anticipated, were nevertheless a shock after 4 long years of war. The German Army, having been checked earlier that Spring and subsequently driven-back over the Hundred-Days-Offensive, was now engaged in a general retreat all along the Western Front. As such, all Allied Forces opposing them were to adopt an aggressive disposition in order to exert constant pressure on and exploit any weaknesses in the German lines. Marshal Foch stressed that these orders were to be followed at once, so as to ensure that the Germans were given no opportunity to organize a defense. From Marshal Foch these orders passed to the commander of the American Expeditionary Forces, General John J. Pershing, and from him to the commanding general of the US Second Army, Robert L. Bullard. However, when Bullard relayed these orders to his Corps commanders, they were dismayed. Though the Second Army had spent the last week planning their own operations against the Germans, many were still in varying states of disorganization when Marshal Foch’s orders reached them. Regardless, General Bullard was adamant; All forces under his command must advance on 10 November.

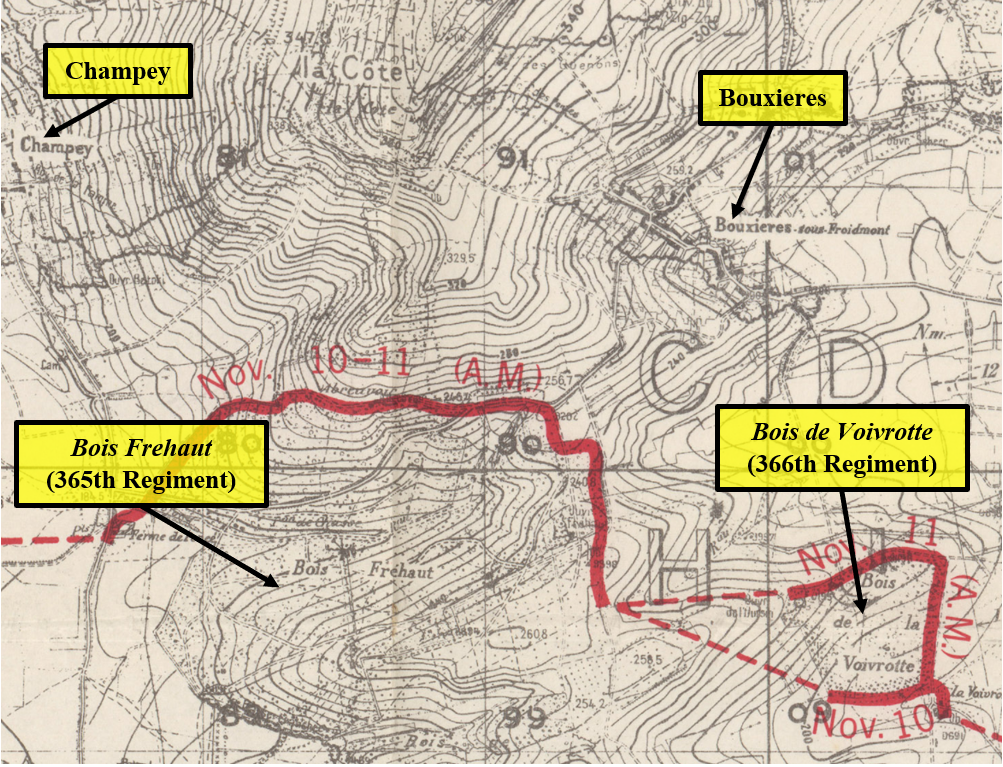

In the 92nd Division’s sector, the 2nd Battalions from both the 365th and 366th Infantry Regiments moved to their jump-off points in Pont-a-Mousson and on the northern edge of the Foret-de-Facq, respectively. These units, which had gained an intimate understanding of the terrain and enemy to their front through roughly a month of combat patrols and trench raids, were designated as the assault battalions of the 183rd Infantry Brigade, 92nd Division, under the command of the newly formed American VI Corps. With direct support from the 350th Machine Gun Battalion and 167th Field Artillery Brigade, they had been given the task of advancing the 92nd Division’s frontline between the Moselle and the Seille rivers. Specifically, the 365th Infantry Regiment had been tasked with capturing the Bois Frehaut while the 366th Infantry Regiment was assigned to take the smaller Bois de Voivrotte and Bois de Cheminot, which would collectively serve as staging areas for the next phases of the 92nd Division’s operation. However, though the men of the 183rd Infantry Brigade were well prepared for this task, that did not mean that it would be easy.

Over the course of the last month, the German artillery opposite Second Army had been engaged in a series of systematic contamination shoots, the purpose of which was to discourage or make impossible a large-scale offensive targeting the German Fortress at Metz. Naturally, it was expected that the Germans would continue to dissuade the Second Army’s advance using chemical weapons, and so it was necessary for the Second Army to take extra measures to protect against gas. In the 92nd Division, gasmask inspections were conducted through the evening of 9 November and sag-paste was issued to protect vulnerable body parts from chemical irritants. Artillery units in the Second Army had also amassed their own collections of gas shells, including No. 5 (Phosgene), No. 6 (Chloroformate Lachrymator), and No. 20 (Yperite) shells to be used only with express authorization. It is unclear how many, if any, of these shells were actually fired during the coming Woevre Plain Operation.

Also on 9th November, Major General Charles C. Ballou, who had commanded the 92nd Division since it was mustered in 1917, was promoted to command the US Army VI Corps. Major General Charles H. Martin, who had previously served with the 86th Division, replaced General Ballou as commander of the 92nd Division. While General Martin had prior combat experience, having been briefly present for the Meuse-Argonne Offensive for instance, this would be his first time leading a division in combat.

10 November, 1918

On the night of 9th November through the early hours of 10 November, the officers of the 92nd Division met to finalize their plans. They decided that the assault battalions from the 365th and 366th Infantry Regiments, which together formed the 183rd Infantry Brigade, should secure their initial objectives, the Bois Frehaut, Bois de Voivrotte, and Bois de Cheminot, by the end of 10 November. From these forward positions, the 183rd Infantry Brigade could then make a general push towards Corny-Sur-Moselle. Meanwhile, on the left bank of the Moselle River, the 367th Infantry Regiment, 184th Infantry Brigade, was to work closely with the US 7th Division under the command of IV Corps and cover the right flank of the 7th Division’s attack on the Preny Heights. From its elevated position on the west bank of the Moselle, the 367th Infantry Regiment was also tasked with giving covering fire to the elements of the 183rd Infantry Brigade advancing on the other side of the river. The 368th Infantry Regiment was designated as the divisional reserve and moved to a supporting position. While the officers of the 92nd Division had originally planned to begin their operation at 0500 Hours (5:00 AM), orders came through for the entirety of the Second Army to attack in unison at 0700 Hours (7:00 AM).

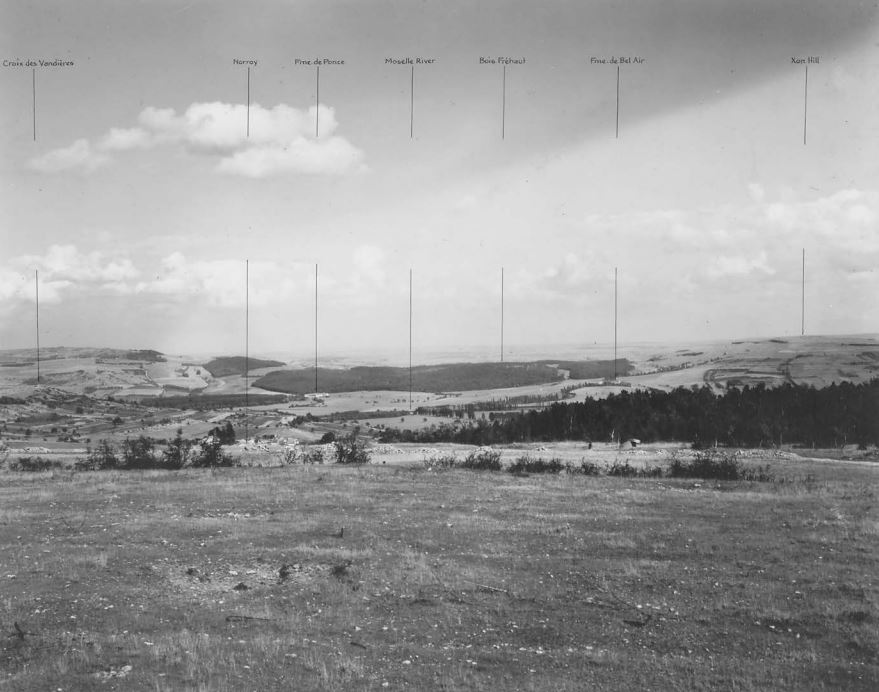

The view of the 183rd Infantry Brigade’s Area of Operations from the 367th Infantry Regiment’s position on the West Bank of the Moselle River.

“Artillery at work in a French forest. This was a phase of operation in which the […] units of the 167th [Field Artillery] Brigade distinguished themselves in the closing days of the war.”

The 366th Infantry Regiment faced similar difficulties during their advance on the Bois de Voivrotte. The two attacking platoons from [F] Company reached the southern edge of the woods by 0800 Hours (8:00 AM) and a short while later, at 0812 Hours (8:12 AM), the 366th Infantry Regiment reported that they had captured the Bois de Voivrotte and taken 3 Germans prisoner. However, by 0900 Hours (9:00 AM) a new report stated that they were losing ground under withering German machine-gun and artillery fire. 2nd Battalion, 365th Infantry Regiment, reported similarly heavy fire in their sector as well. Regardless, by 1100 Hours (11:00 AM) the 183rd Infantry Brigade had successfully secured all of its initial objectives. The same could not be said for the neighboring element of the Second Army, the 56th Infantry Regiment, 7th Division, whose failed attack on the Preny Heights West of the Moselle River prevented the 367th Infantry Regiment from advancing their own frontline.

By midday, the 92nd Division’s front had largely stabilized. Repeated counter-battery fire by the 167th Field Artillery Brigade had discouraged the German guns somewhat, though Yellow Cross (Mustard Gas), Green Cross (Diphosgene), and Blue Cross (Diphenylchlorarsine) shells continued to saturate the Bois Frehaut and Bois de Voivrotte throughout the day. Further, though enemy fire had forced them to fall back to the southern edge of the Bois de Voivrotte earlier that morning, the two platoons from Company [F], 366th Infantry Regiment, began to reclaim the northern edge of the woods at 1230 Hours (12:30 PM). Altogether, the 183rd Infantry Brigade, 92nd Division, had made the best advance of any unit in the Second Army’s front, a fact that the division’s new commander, Major General Martin, wished to capitalize on.

At 1450 Hours (2:50 PM), orders were issued to the commanders of the 183rd Infantry Brigade to continue their advance at 1700 Hours (5:00 PM). Their new objective was to secure the fortified hill between Champey and Bouxieres, which held a commanding view of the sector. The 1st Battalion, 365th Infantry Regiment, which was in the process of reinforcing 2nd Battalion in the Bois Frehaut, was entrusted to lead this attack. Meanwhile, the 366th Infantry Regiment was ordered to prepare for a simultaneous attack on Bouxieres, which would hinder the Germans’ ability to reinforce the heights from the East. However, at 1505 Hours (3:05 PM) the commanding officer of 2nd Battalion, 366th Infantry Regiment again sent word that, due to a devastating barrage from the German Artillery and overwhelming machine-gun fire, his soldiers were again forced to withdraw to the southern edge of the woods. At roughly the same time, the 365th Regiment also reported that some 145 officers and enlisted men had been gassed in the Bois Frehaut. Consequently, at 1555 Hours (3:55 PM) the orders for the 183rd Brigade to resume the offensive were rescinded. Instead, it was decided that, in the face of surprising enemy resistance, the 92nd Division should take the night and following morning to reorganize and secure their gains.

Elsewhere in Europe, the wheels of history were turning.

11 November, 1918

At midnight on 11 November the 366th Infantry Regiment was ordered to retake the Northern Edge of the Bois de Voivrotte in preparation for the next phase of the attack. Moving carefully under the cover of darkness, 2nd Battalion, 366th Infantry Regiment, reported that they were fully in position at the northern edge of the Bois de Voivrotte at 0300 Hours (3:00 AM). Roughly an hour later, they were again subjected to an enemy barrage, but the 366th Infantry Regiment reported no casualties. At 0500 Hours (5:00 AM), the 167th Field Artillery returned the Germans’ gesture, and began a rolling barrage in advance of the Infantry’s attack. However, at 0718 Hours (7:18 AM), the 92nd Division received the most anticipated news of the entire war: Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany had signed an Armistice with the Allied Forces. The War to End All Wars had, at long last, come to an end, and a ceasefire would go into effect at 1100 Hours (11:00 AM). Unfortunately, the men of the 92nd Division were already well into their offensive when this news reached the frontline, and the Germans had little interest in simply allowing the Americans to return to their trenches without a fight. Thus, though the war was effectively over, the 92nd Division had to endure a swirling maelstrom of bullets, gas, and high-explosive shells until the very end.

Gun crew from Regimental Headquarters Company, 23rd Infantry, firing 37mm gun during an advance against German entrenched positions.

It is sadly unclear what Private Tom Rivers’ role was in this closing chapter of the First World War, although several inferences can be made. The first is that he may have been his unit’s message runner – an unenviable and dangerous, though invaluable, position – though it is also possible that he simply volunteered for this role when an officer called for runners. The second is that the support companies mentioned in the citation were most likely the companies from the 167th Field Artillery Brigade and 350th Machine-Gun Battalion which had been attached to the 365th and 366th Infantry Regiments. These companies’ roles would have been to operate heavy weapons in support of the Infantry, including machineguns, Stokes Mortars, and 37mm Assault Cannons. Finally, the “important messages” also mentioned in the citation for Rivers’ Distinguished Service Cross may have been to direct the fire of these heavy weapons or, due to the unique circumstances, could have been the final orders to cease fire, which were delivered at 1045 Hours (10:45 AM). Now, with these inferences in mind, Tom Rivers’ story can begin to take shape.

In the closing hours of the First World War, the foremost elements of the 92nd Division were subjected to prolonged bombardment by the German guns. The air became so thick with toxic gases that it was estimated nearly 1,000 Blue, Green, and Yellow Cross shells had fallen in the 366th Infantry Regiment’s sector alone, wounding nearly 200 men. One of these men was Private Tom Rivers. However, rather than withdrawing for medical attention, Private Rivers chose to remain in danger. Even as toxic fumes choked him and burned his lungs, he courageously dashed through the battlefield, message in hand. Even as the boom of artillery shook the earth and the rattle of machine-guns counted down the last bloody seconds of the Great War, Private Rivers pushed through the enemy fire that saturated the space between friendly lines. He ran right up until the eleventh hour, when the thunder of artillery slowed, sputtered, and stopped. Then, the sporadic cracks of rifle fire and bursts of machineguns went quiet and, for the first time in over four years of brutal, bloody, war, an eerie sense of quiet and calm settled over the fields, hills, and valleys of the Western Front. His mission now fulfilled, Private Rivers at last left the field.

For this extraordinary act of heroism, Private Rivers was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross under General Orders No. 44.