Edward Howard Handy

Edward Howard Handy’s Personal Narrative was derived from information found in public records, military personnel files, and local/state historical association materials. Please note that the Robb Centre never fully closes the book on our servicemembers; as new information becomes available, narratives will be updated to appropriately represent the life story of each veteran.

Please contact the Robb Centre for further clarification or questions regarding content or materials.

Military Honor(s):

Distinguished Service Cross

Citation: The President of the United States of America, authorized by Act of Congress, July 9, 1918, takes pleasure in presenting the Distinguished Service Cross to Private First Class Edward H. Handy (ASN: 1799754), United States Army, for extraordinary heroism in action while serving with Company B, 368th Infantry Regiment, 92d Division, A.E.F., at Binarville, France, 30 September 1918. Private Handy, with an officer and another soldier, voluntarily left shelter and crossed an open space 50 yards wide swept by shell and machine-gun fire to rescue a wounded soldier, whom they carried to a place of safety.

Croix de Guerre with Silver Gilt Star

Citation: French Croix de Guerre with Gilt Star, under Order No. 17.470 “D”, dated May 17, 1919. “An admirably courageous soldier---".

Life & Service

- Birth: 9 August 1893, Falls Church, VA, United States

- Place of Residence:

- Race/Ethnicity: African American

- Death: 5 September 1922 Washington, DC, United States

- Branch: Army

- Military Rank: Private First Class

- Company: [B]

- Infantry Regiment: 368th

- Division: 92nd

Edward Howard Handy was born to Thomas (?-?) and Hannah (1860-?) on 9 August 1893 in Church Falls, Virginia. Edward was the second youngest of eight children; Annie (1876-?), Ada (1883-?), Lucinda (1884-?), Robert (1886-1924), Thomas (1888-?), Rosena (1889-1965) and Laura (1893-1976).

In his youth, Edward worked various labor jobs in Church Falls before moving to Washington, D.C. sometime in the 1910s.

It is unknown as to when Edward enlisted in the Army; Private Handy and his company left Hoboken, New Jersey on the U.S. Army Transport Ship George Washington on 15 June 1918, arriving in Brest, France on 21 June. Then-Private First Class Handy received the Distinguished Service Cross and French Croix de Guerre with Gilt Star for his actions on 30 September, 1918, near Binarville, France;

“The President of the United States of America, authorized by Act of Congress, July 9, 1918, takes pleasure in presenting the Distinguished Service Cross to Private First Class Edward H. Handy (ASN: 1799754), United States Army, for extraordinary heroism in action while serving with Company B, 368th Infantry Regiment, 92d Division, A.E.F., at Binarville, France, 30 September 1918. Private Handy, with an officer and another soldier, voluntarily left shelter and crossed an open space 50 yards wide swept by shell and machine-gun fire to rescue a wounded soldier, whom they carried to a place of safety”.

Awarded DSC by CG, AEF, November 17, 1918. Published in G.O. No. 20, W.D., 1919.

French Croix de Guerre with Gilt Star, under Order No. 17.470 “D”, dated May 17, 1919. “An admirably courageous soldier—.”

Private First Class Handy returned to the United States in the Spring of 1919 and was Honorably Discharged.

Edward Handy served with Company [B], 1st Battalion, 368th Infantry Regiment, 184th Infantry Brigade, 92nd Division of the American Expeditionary Force. During combat in the vicinity of Binarville, Pvt. Handy would take part in a rescue mission alongside two other men, for which he would be awarded the Distinguished Service Cross.

28 September, 1918:

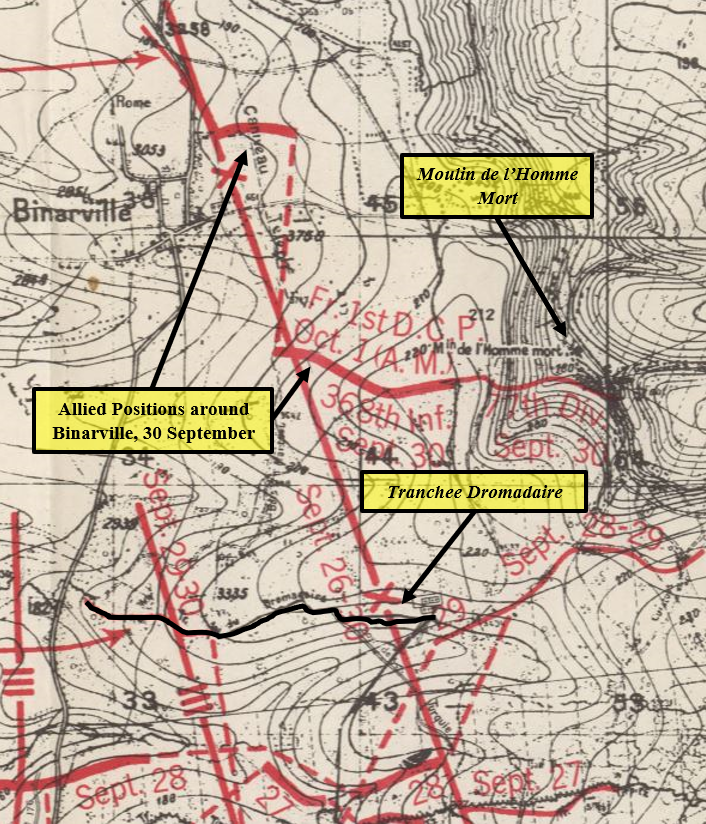

During their part in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, the 368th Infantry Regiment was partnered with the French 11th Cuirassiers to form Groupement Durand. The purpose of this ad-hoc unit was to plug the hole between the French 1st Dismounted Cavalry Division and the American 77th Division to their right and left respectively, and to maintain communications between these units. However, in order to do so they would have to advance through a heavily fortified section of the Argonne Forest to the south of Binarville, where the Germans had been entrenched since the war came to a grinding halt in 1914.

Facing four years of defensive build-up, including numerous trench systems and miles of overgrown barbed-wire, after four days of constant offensive movements the 368th Infantry Regiment had reached its breaking point. However, as if the constant noise of the German machine-guns and earth-shaking power of their artillery wasn’t enough, the very environment of the Argonne proved hostile to the men. While the temperature had yet to reach freezing, constant rainfall soaked through the men’s uniforms, chilling them to the core. Craters, which might have otherwise been used for cover while advancing through no-man’s land, flooded and the slopes beneath the German lines grew slick with mud, further slowing their advance. Oftentimes, the men of the 368th Infantry Regiment had no choice but to advance along the German’s communication trenches, but these routes were narrow and predictable; they were the perfect environment for booby-traps and ambushes.

Having already lost too many good men, the company commanders of the 2nd and 3rd Battalions, 368th Infantry Regiment, could no longer be motivated to attack by the end of 28 September. Only 1st Battalion, which had previously been held in reserve, was still combat-capable. With over half of the regiment being broken, it was decided that the 368th should be recalled from frontline duty.

29 September, 1918:

Though the French cavalry no longer fought from horseback, they still held to many strong cavalry traditions.

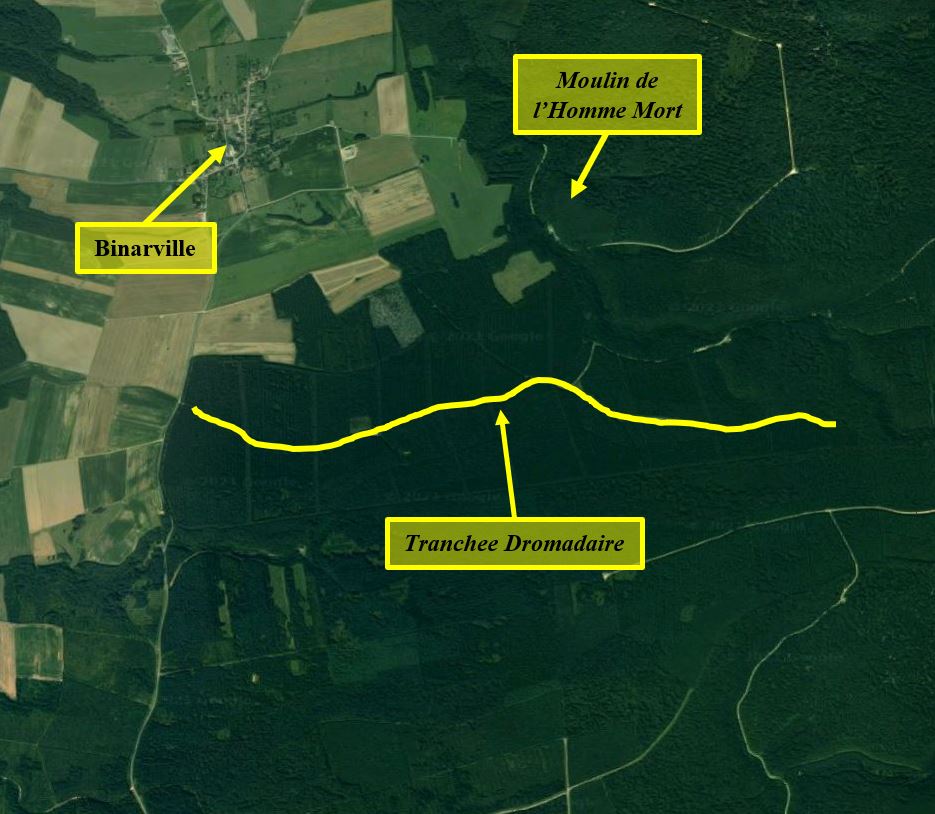

On 29 September, the French 9th Cuirassiers and 10th Dragoons assumed control of the 368th Infantry Regiments zone. These dismounted cavalry units had previously held positions on the left-flank of Groupement Durand, but with the 368th incapable of further action the attack on Binarville would be entrusted to them. They spared no time in commencing their attack, and at 1800 hours (6:00 PM) they fell onto the German lines at Tranchee Dromadaire. However, while the French had intended to fully secure this line in preparation for the final push to Binarville, the German defenses proved too strong, and the offensive once more stalled. Fortunately, that night the Germans judged that their position in Tranchee Dromadaire was no longer tenable, and withdrew their forces.

30 September, 1918:

On the morning of 30 September, scouts from 1st Battalion, 368th Infantry Regiment, found the German lines to their front uninhabited. Not willing to let an opportunity escape him, the commander of 1st Battalion, Colonel John Merrill ordered his forces to advance and secure the empty trench. However, this decision came at his own initiative, and was contrary to his expected maneuvers. Likely as a consequence of this unexpected movement, 1st Battalion would not receive orders to fall back and regroup with the rest of the 92nd Division. Thus, while 2nd and 3rd Battalions were relieved from their duties, 1st Battalion remained at the front. At 1200 Hours (12:00 PM), lookouts from 1st Battalion, 368th Infantry Regiment observed the French 9th Cuirassiers moving forward on their left. The final push to Binarville had begun.

An American machine-gunner watches over the open ground between ridgelines. Germans guns placed in positions similar to this were a constant threat in the Argonne.

Possibly believing that his own orders to advance had been delayed, Col. Merrill rallied his men. At 1400 hours (2:00 PM), they joined the French in the field under a heavy storm of rain, bullets, and artillery shells. Moving quickly, the American and French troops captured Binarville by 1600 hours (4:00 PM). However, their victory had not come yet; German defenders stationed on a ridgeline to their East were able to direct accurate artillery, machine-gun, and rifle fire on the Allied positions in and around Binarville. Many men would be caught by this flurry of death as they advanced through the cratered fields that surrounded the crumbling village, tempting others to undergo daring rescue-missions into no-man’s land.

On one such occasion, a soldier was struck down nearly 50 yards from the nearest friendly troops on the other side of a wide-open field. Not willing to leave their brother-in-arms to bleed-out in the mud, Private Edward Handy and two other men, one of whom may have been Private Thomas H. Davis, braved themselves against the danger. In clear view of the very same guns that had already wounded one man, the trio broke from their shelter in a mad-dash over the barren earth. Thunderclaps of artillery shook the mud-slick ground beneath their feet and bullets whizzed past them, but the men pushed forward. Securing the wounded man, they then turned back the way they had come and ran the gauntlet once more.

In the evening of 30 September, runners would finally reestablish contact between the battalions of the 368th Infantry Regiment. 1st Battalion, having held their ground, would at last retire from the front.

For his part in this incredible mission, Private Edward Handy would be awarded the Distinguished Service Cross. Additionally, Pvt. Handy would also receive the French Croix de Guerre with Silver Gilt Star for being “an admirably courageous soldier.”

Edward lived in Washington, DC, the remainder of his life. Whilst attending a fair in late August 1922, he became involved in a fight with two other men. Edward and friend Daniel Brown were both shot during the altercation with Charles Collins- Edward in the head and Daniel in the stomach.

Edward did not survive the incident, and died at the Georgetown Hospital in Washington, D.C. on 5 September 1922.