John Baker

John Baker’s Personal Narrative was derived from information found in public records, military personnel files, and local/state historical association materials. Please note that the Robb Centre never fully closes the book on our servicemembers; as new information becomes available, narratives will be updated to appropriately represent the life story of each veteran.

Please contact the Robb Centre for further clarification or questions regarding content or materials.

Military Honor(s):

Distinguished Service Cross 12 February 1919

Citation: The President of the United States of America, authorized by Act of Congress, July 9, 1918, takes pleasure in presenting the Distinguished Service Cross to Private John Baker (ASN: 2716416), United States Army, for extraordinary heroism in action while serving with Company I, 368th Infantry Regiment, 92d Division, A.E.F., near Binarville, France, 28 September 1918. Although severely wounded in the right hand, losing two fingers, Private Baker, a runner continued three hundred yards through heavy enemy machine-gun fire to the forward battalion, and delivered his message alone, having been deserted by an unwounded fellow runner.

Life & Service

- Birth: 26 March 1898, Cape Charles, VA, United States

- Place of Residence:

- Race/Ethnicity: African American

- Death: 24 December 1938 Philadelphia, PA, United States

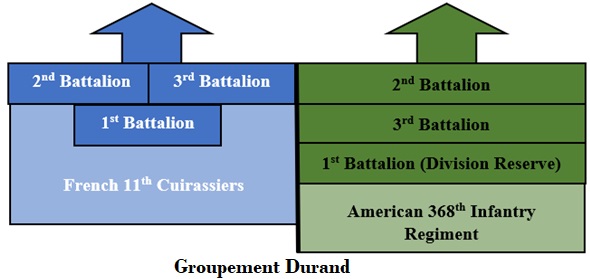

- Branch: Operated as part of the Franco-American liaison Group organized as a provisional brigade knownas Groupement Durand AKA Groupement Rive Droite (operating as the right element of the French 1st Dismounted Calvary Division between the 77th Division, I Corps and French XXXVIII Army Corps, French Fourth Army) Army

- Military Rank: Private

- Company: [I]

- Infantry Regiment: 368th

- Division: 92nd

John Baker was born to Henry Baker (1872-?) and Princess Saunders (1872-1951) on 26 March 1898 in Cape Charles, Northampton, Virginia, the fourth of twelve children (siblings listed below are a combination of Census lists, paperwork submitted by Henry and Princess Baker, etc.; the list is most likely incomplete and inaccurate); Sarah (1893-1936), Sidney Saunders (1895-1982), Viola (1896-?), Nannie (1900-1917), Lenwood (1901-?), Alma (1904-?), Ethel (1905-1924), Rustine (1908-?), Seatine (1908-?), Naomi (1910-2003) and Thelma Mildred (1914-2005).

Baker worked as a farmer, hostler, and fireman into his teens. In the late 1910s, Baker worked as a laborer for Millbourne Mills Company, located on 63rd and Market St. in Philadelphia.

Baker enlisted in the U.S. Army on 29 April 1918 in Philadelphia, serving as a Private with Company I, 368th Infantry Regiment, 92nd Division. Pvt Baker and his company left Hoboken, New Jersey aboard the U.S. Army Transport Ship George Washington on 15 June 1918, arriving in France on 21 June. Pvt Baker received the Distinguished Service Cross and French Croix de Guerre with Gilt Star for his actions on 28 September 1918 near Binarville, France;

“The President of the United States of America, authorized by Act of Congress, July 9, 1918, takes pleasure in presenting the Distinguished Service Cross to Private John Baker (ASN: 2716416), United States Army, for extraordinary heroism in action while serving with Company I, 368th Infantry Regiment, 92d Division, A.E.F., near Binarville, France, 28 September 1918. Although severely wounded in the right hand, losing two fingers, Private Baker, a runner continued three hundred yards through heavy enemy machine-gun fire to the forward battalion, and delivered his message alone, having been deserted by an unwounded fellow runner.”

“Soldier of admirable courage. Although severely wounded in the right hand, continued to run a distance of 300 meters in spite of violent machine gun fire in order to deliver his message to an advance battalion.”

Baker sustained “eye and ear trouble, loss of 2nd finger of right hand as well as stiff index finger of right hand”; he recovered at “Base Hospital 10, 2 days; Base Hospital 76, 2 months; Base Hospital 8, 6 weeks”. Pvt Baker returned to the United States on 1 January 1919; he was Honorably Discharged on 31 January 1919, with an assignment to Company 52, 13th Battalion, D.B. Camp Dix, New Jersey.

Service: Act of Valor

Private John Baker served in Company [I], 3rd Battalion, 368th Infantry Regiment, 184th Infantry Brigade, of the 92nd “Buffalo Soldiers” Division during the time of his act of valor, on the 28th of September, 1918. Private Baker and the 368th Infantry Regiment operated as part of the Franco-American liaison group organized as a provisional brigade known as Groupement Durand under the command of the French Fourth Army. The following is his story:

Binarville, France – 28 September 1918

To fully grasp the deed of Private John Baker, it is important to see the prelude of the date of his act and how it influences John Baker’s heroic and selfless actions:

24 September 1918:

At 0500 hours (5:00 A.M.) the 368th Infantry Regiment of the 92nd Division completed an all-night march with the objective of ensuring that the regiment would be in a position and to relieve a battalion of the French 11th Cuirassiers. Shortly after arrival to the outskirts of the Argonne Forest at 0900 hours (9:00 A.M.), the 368th Infantry Regiment moved into Camp Sounait and reported to the French 1st Dismounted Cavalry.

With only 4 hours of rest, the 368th Infantry Regiment began another arduous march to join the French XXXVIII Corps at 2100 hours (9:00 P.M.). Meanwhile the remainder of the 92nd Division proceeded to the northwest region of the Argonne Forest to assume reserve positions.

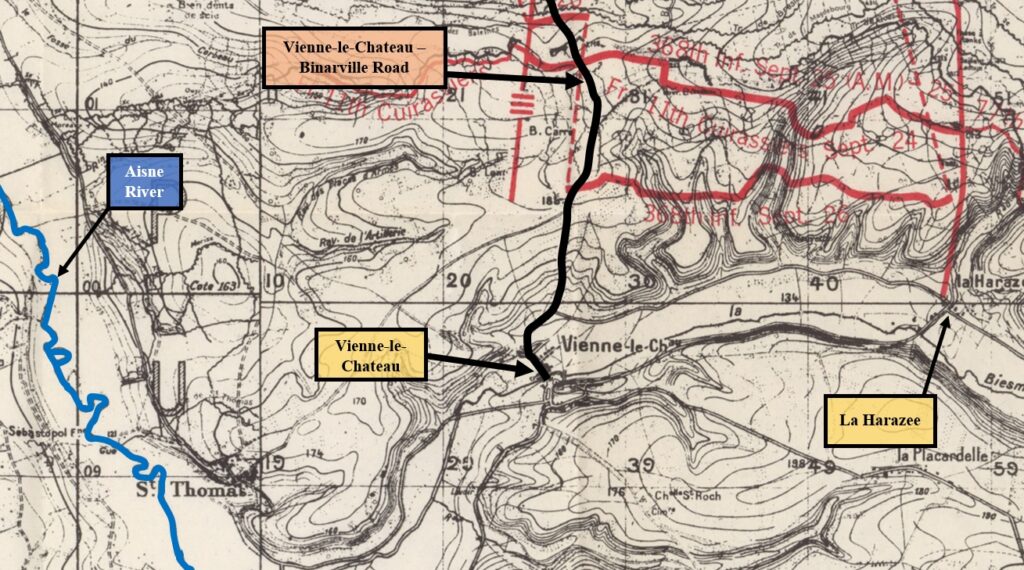

Now detached from the rest of the 92nd Division, the 368th Infantry Regiment proceeded to the right bank of the Aisne River, just north of Vienne-le-Chateau and La Harazee, with orders to relieve the 1st Battalion of the French 11th Cuirassiers. However, their movement had been slowed due to the muddy conditions as well as the abandoned trucks, carriages, and other vehicles that littered the Verdun Highway.

Exhausted from traveling over 300 miles by train, truck, and foot between 21 to 24 September 1918, the 368th Infantry Regiment had arrived to its positions late within the night to begin its relief of the French 11th Cuirassiers. Despite reaching its objective, the 368th Infantry still lacked food rations and water, as well as important equipment such as grenades, light machine-guns, flares, wire cutters, and maps.

25 September 1918:

The sky above the 368th Infantry Regiment was cloudy and after the sun went down, the sky was well lit due to the flashes of artillery guns firing whereby one couldn’t hear a comrade speak beyond a few feet due to the immense roar of the continuous firing of the artillery cannons and thundering booms of the shells blasting along the battlefield. The air was filled with the stench of rotting bodies of soldiers and horses, and the exhausting march through the hills and soggy soil left the men of the 368th Infantry exhausted.

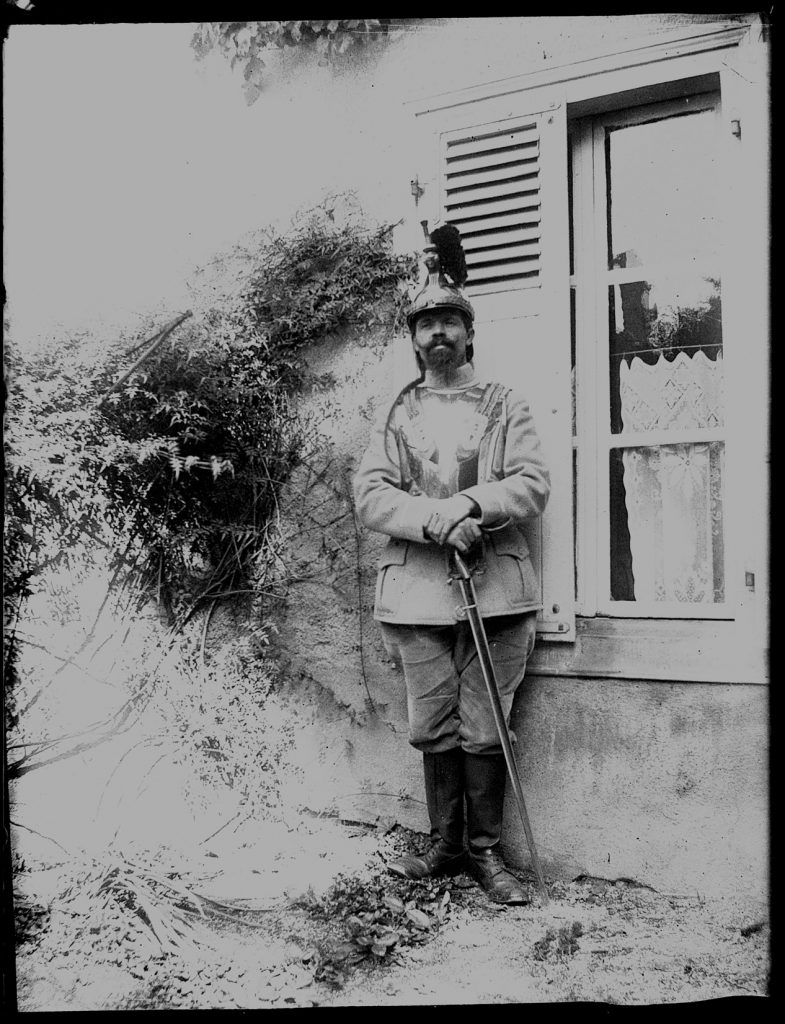

During the evening of 25 September 1918, the 368th Infantry, detached from the rest of the 92nd Division, was assigned to the Franco-American liaison group known as Groupement Durand. Under command of the French Tenth Army, Groupement Durand consisted of the French 11th Cuirassiers and the 368th Infantry Regiment, and was assigned to operate as the liaison group to maintain communications between the French 1st Cavalry Division, to its left, and the American 77th Division, located to the right. Groupement Durand’s mission, while seemingly simple, was nearly impossible due to equipment and ration shortages, terrain, weather, translation difficulties, as well as the emboldened German defenses. Along the 368th Infantry Regimen’s front, there were vast stretches of no man’s land followed by camouflaged German machine-gun emplacements that were tucked behind layers of barbed wire and chevaux-de-frise.

Groupement Durand‘s first task was to locate itself abreast the French 1st Dismounted Cavalry and the 77th Division. To do so, they would need to cross the Biesme River and maintain surveillance of the German forces, a secondary task was in place for Groupement Durand to pursue the Germans in the case of a withdrawal from the line. After moving from Vienne-le-Chateau, the 368th Infantry took positions on the north and south bank of the Biesme River, along the left flank of the American 77th Division and within a sector opposite of the town of Binarville, France. Although the positions were held by the 2nd and 3rd Battalions of the 368th Infantry Regiment throughout the night, the three companies of the 2nd Battalion located directly along the frontline were dangerously exposed along their north, west, and east flanks due to being located in a spot that had protruded out of the Allied frontline positions.

During the night of 25 September 1918, attack orders were finalized and Groupement Durand were ordered to form a line of resistance as far forward as possible to feel out German positions. This was to be done with patrols with an advance to occur as the opportunity presented itself. The mixed liaison group was told to be ready to meet counterattacks from positions northeast of the Biesme River and the 3rd Battalion of the 368th Infantry were specifically assigned to maintaining liaison as the 2nd Battalion commenced its forward movements.

A 6-hour artillery bombardment was planned to commence at 0530 hours (5:30 A.M.). The 368th Infantry Regiment was to advance to a line extending East and West through the city of Servon and occupy the front line German trenches. Following the capture of the front-line Trenches, Groupement Durand was ordered to reorganize its forces and prepare against any potential German counterattacks. The orders given to Groupement Durand stated to hold its position at all costs and were told German counter-attacks would likely come from the Argonne Forest. In the case of a German retreat, Groupement Durand was ordered to pursue the retreating Germans while simultaneously guaranteeing the safety of their recently secured position. The 368th Infantry Brigade also needed to be prepared to send an advance guard towards Binarville. Additionally, the 1st battalion of the 368th Infantry Regiment was to be prepared to make counterattacks from the Northeast and was not to be actively engaged in the 368th Infantry Regiment’s attack without express authorization. Up to this point, the 368th Infantry Regiment had not suffered any large numbers of casualties, with the exception of 2 officers and 7 men from a German mustard gas attack.

26 September 1918:

On the morning of 26 September 1918, the 368th Infantry Regiment acted as the right element of the Groupement Durand assault. The 368th Infantry regiment succeeded in its initial push securing 1 kilometer before ultimately being forced to withdraw by nightfall. Very quickly, the lack of essential rations became an issue. Lack of water, food, ammunition, heavy wire cutters, automatic rifles, grenades, flares, and the breakdown of wire communication throughout the day created problems across the 368th Regiment’s advance. Company [F] 2nd Battalion, 368th Infantry Regiment, (Groupement Durand), was the first to reach its assigned objectives on the 26th September 1918. It reached the frontline of German trenches without opposition but had split into two groups of two platoons each and was eventually repelled to its departure point, losing the company’s earlier gains. Company [G] 2nd Battalion, 368th Infantry Regiment of Groupement Durand also achieved small gains but were halted from German barbed wire and trenches. Following the failed attacks, at 0800 hours (8:00 A.M.), Major Elser in command of the 2nd Battalion, 368th Infantry Regiment, Groupement Durand, reported that he had lost his way and halted the battalion’s advance. Still, by 1000 hours (10:00 A.M.), 2nd Battalion, 368th Infantry Regiment (Groupement Durand) managed to advance 1.5 Kilometers and by the evening had advanced a further .5 Kilometers but was halted from heavy German resistance. At 1035 Hours (10:35 A.M.), the 368th Infantry Regiment, Groupement Durand, commander Colonel Brown reported “Front battalion still against German wire and working their way through… With no tools nor artillery preparation, the passage of the enemy’s wire is very difficult.”

At this point in time, 3rd Battalion, 368th Infantry Regiment, Groupement Durand, (the Battalion that involves Private Baker) spent the first half of the day advancing to Boyau de Turquie, and the trenches held by 2nd Battalion, 368th Infantry Regiment, Groupement Durand, prior to their advance. In accordance with the operation, they secured and held the trenches previously abandoned by 2nd Battalion 368th Infantry Regiment, Groupement Durand, and held that position while 2nd Battalion retreated through it to behind 3rd Battalion. By 1430 hours (2:30 P.M.), the liaison detachments of the 3rd Battalion, 368th Infantry Regiment (Groupement Durand) had lost contact with the 77th Infantry Division (American 1st Army) on the right flank. Later that day, the liaison elements had also lost the French 11th Cuirassiers along with the rest of the French 1st Dismounted Cavalry Division (French 4th Army). The 368th Infantry Regiment, Groupement Durand, urgently dispatched a platoon to recover contact with the left side of the 368th Infantry Regiment’s lines. This platoon failed to re-establish contact and did not return to the Regiment for the rest of the operation.

368th Infantry Regiment, Groupement Durand, Headquarters had still not been able to find the 2nd Battalion by early afternoon. Unknown to 368th Regimental Headquarters, the 2nd Battalion had become dispersed all over the sector, all the way down to platoon and squad levels, following the retreat of the 2nd Battalion from its previous advance. This was due to heavy German resistance, artillery bombardment, uncut barbed wire, and inexperienced officers. In the late afternoon, at an unspecified time, a German aircraft strafed companies from 2nd Battalion 368th Infantry Regiment, Groupement Durand, and dropped a single bomb, resulting in widespread terror and uncoordinated retreats across the disjointed lines. Major Elser, commander of the 2nd Battalion had lost all communication with all other companies in the battalion as well as his rear headquarters. By dusk, the battalion was in complete disarray and had fallen apart into smaller units without communication to one another.

By late afternoon of 26 September 1918, Companies [E] and [H] of 2nd Battalion, had withdrawn from their previously held frontline positions due to a claim of being out of water. By the night of 26 September 1918, the companies had received a water shipment and would spend the next morning re-securing the frontline positions they held earlier. With the exception of these 2 companies, 2nd Battalion 368th Infantry Regiment, Groupement Durand, existed only on paper, as most units within its ranks were yet to be found and dispersed over the entire 368th Infantry Regiment’s sector. The reason for the failed assault by the 368th Infantry Regiment, specifically 2nd Battalion 368th Infantry Regiment, Groupement Durand, was cited as 2 major reasons.

- French preemptive artillery strikes across the frontline were shorter than ordered (due to desire to save shells) and inaccurate. The direct result of this was German barbed wire remained undisturbed, as well as German fortifications and soldiers remaining capable of defending their lines

- The lack of wire cutters amongst the 2nd Battalion’s ranks meant that the barbed wire could only be cut at a slow pace, if at all. This, coupled with well-equipped and experienced German soldiers, as well as inexperienced and exhausted American troops caused the 2nd Battalion’s advance to halt quickly and eventually shatter under heavy enemy fire.

Following the failure of 2nd Battalion 368th Infantry Regiment, Groupement Durand, 1st Battalion, also of the 368th Infantry Regiment, Groupement Durand, which had been acting as a reserve force, was deployed from its initial position at Haute Batis to P.C. Capinere. Groupement Durand received a welcome piece of good news following sunset when liaison was reestablished with the American 77th Division (American I Corps, American First Army). Despite this, by nightfall, the overall liaison between the French 4th Army, and the American 1st Army had not been re-established. During the night, the remaining soldiers of companies [E], and [H] of 2nd Battalion, 368th Infantry Regiment, Groupement Durand, withdrew behind 3rd Battalion and began to regroup and plan the second attacks on the positions they held and lost earlier in the day. This situation left the 3rd Battalion, 368th Infantry Regiment, Groupement Durand, on the frontline defense against the German counterattack. Companies [G] and [M] of 2nd Battalion remained isolated in front and to the West of American lines, in the town of Tranche des Baleines. By 2359 Hours (11:59 P.M.), the line held by 3rd Battalion 368th Infantry Regiment, Groupement Durand, was the only organized line held by the 368th Infantry Regiment (With the exception of company [G] and [M] in Tranche de Baleines). The remaining companies of 2nd Battalion 368th Infantry Regiment, Groupement Durand, were either lost in front of American lines, dispersed amongst 3rd Battalion, 368th Infantry Regiment, Groupement Durand, or attempting to regroup behind the frontline for attacks to occur on 27 September 1918.

The line held by the 3rd Battalion, 368th Infantry Regiment, Groupement Durand, was absolutely vital to the overall success of the operation. Should the line collapse, the overall advance of the American First Army, as well as the advance of the French 4th Army, would be halted as the threat of a German surge through the gap could risk the flanks of both armies. Despite the seemingly desperate position 2nd Battalion 368th Infantry Regiment, Groupement Durand, was in, reported casualties from the 26th September 1918 for the Battalion were listed as just 1 death, 19 wounded and 2 gassed. It should be noted that these numbers were most likely higher, as it was near impossible to get an accurate number due to the confusion and collapse of the unit structure during the day. Just one German prisoner was returned to American lines, from the German 7th Company, 2nd Battalion, 83rd Landwehr Regiment, 76th Landwehr Infantry Brigade, 9th Landwehr Division, Army Group Grand Prince of the German 3rd Army.

27 September 1918:

On the morning of 27 September 1918, 2nd Battalion, 368th Infantry Regiment, Groupement Durand, had hastily regrouped into some semblance of an organized unit for the first time since the previous morning. With the 2nd Battalion back into communication with the units on either side, the 1st Battalion (368th Infantry Regiment, Groupement Durand) was able to remain in a reserve role behind the 2nd and 3rd Battalion. Although the 2nd Battalion had regrouped, scattered platoons remained across the previous day’s battlefield. These units would spend the next days regrouping with the American units, joining with the rest of the advance, or would end up being captured by patrolling German units. The mission of the 2nd and 3rd Battalion in the early morning of 27 September 1918, was to advance toward Tranchee Clotilde and Tranchee Dromadaire and establish reconnaissance and patrol groups ahead of the main line. They simultaneously would need to maintain liaison with the right and left flanks (American 1st Army and French 4th Army respectively) as well as taking and holding a line along Vallee Moreau to Binarville road.

At 0345 (3:45 A.M.) on 27 September 1918, the 368th Infantry Regiment received orders to advance to the line at Tranchee Clotilde. To help the 368th accomplish this mission, the American 1st Army placed an unspecified number of 75mm artillery guns under the 368th Regiments, Groupement Durand, command. Once the 368th Regiment advanced to the ordered position, they received the attack order for the assault on Tranchee Clotilde. This called for the 2nd Battalion, with the 1st still in reserve, to attack at 0515 hours (5:15 A.M.). This combined assault from the 2nd Battalion, with the help of the 75mm guns would secure and hold the town at all costs. Despite the orders, the attack was delayed an unspecified amount of time due to an argument between Colonel Fred Brown (commander of the 368th Infantry Regiment) and Major Elser (2nd Battalion Commander). Following the argument, Major Elser gave orders for the 2nd Battalion, 368th Infantry Regiment, Groupement Durand, to pursue an attack on Tranchee Clotilde. Despite the orders, the attack was delayed and in the case of some companies, outright ignored due to the continued dysfunction of the 2nd Battalion following its routing earlier the day before. Out of the entirety of the 2nd Battalion, just 2 companies would be able to carry out their orders on the morning of 27 September. These were Company [G] of 2nd Battalion, who attacked Tranchee des Baleines but was repelled by heavy machine-gun fire, and Company [H], which supported the 3rd Battalion advance. Following the attack, the 2nd Battalion pulled behind the 3rd Battalion and would remain following the 3rd Battalion for the rest of the early morning.

3rd Battalion, 368th Infantry Regiment, Groupement Durand, was entirely intact and was prepared for the next morning’s assaults. Company [H] as well as Company [I] (Private John Baker’s company) was placed on the front line and tasked with heading the attack. Company [L] and Company [E] of 3rd Battalion, 368th Infantry Regiment, Groupement Durand, was to be held back in reserve and support roles of the main attack force. After the extensive delays during the early morning, the 3rd Battalion, 368th Infantry Regiment, Groupement Durand, arrived at its zone of action at 0730 Hours (7:30 A.M.) The 3rd Battalion, under the command of Major Benjamin F. Norris, attacked at 0900 Hours (9:00 A.M.) Facing hospitable terrain, light German resistance and with rested troops who had been sparsely engaged the day before, the battalion made quick and decent progress over the ordered attack sector.

At 1130 hours, (11:30 A.M.), the 2nd Battalion, 368th Infantry Regiment, was brought up from its position at the rear of the 3rd Battalion, 368th Infantry Regiment, and launched an assault that progressed 2 Kilometers against heavy enemy fire. The advanced positions would be held by the 2nd Battalion until 0900 Hours (9:00 A.M.), the following morning.

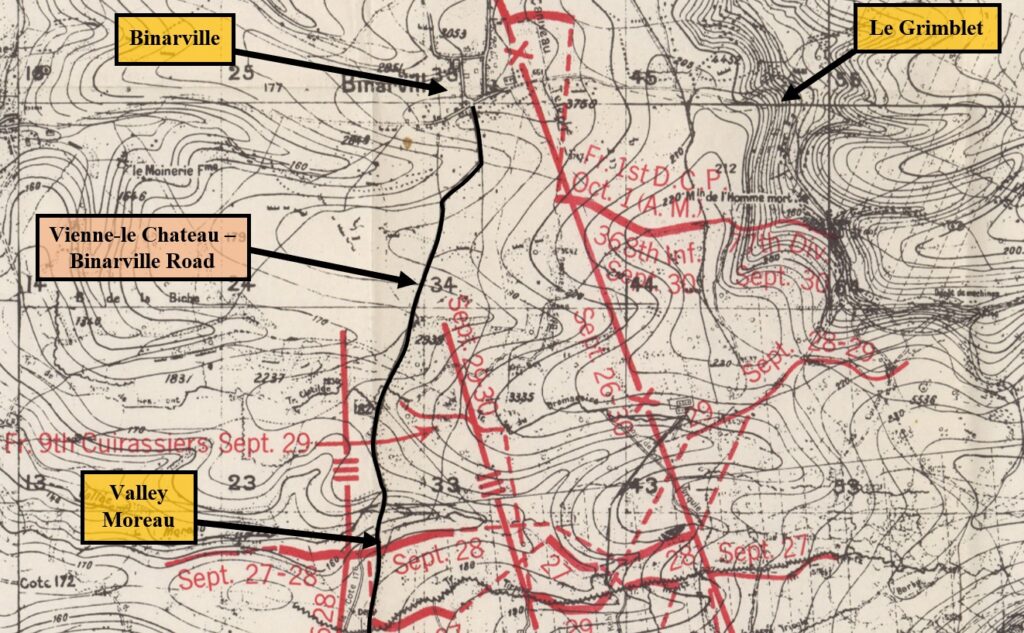

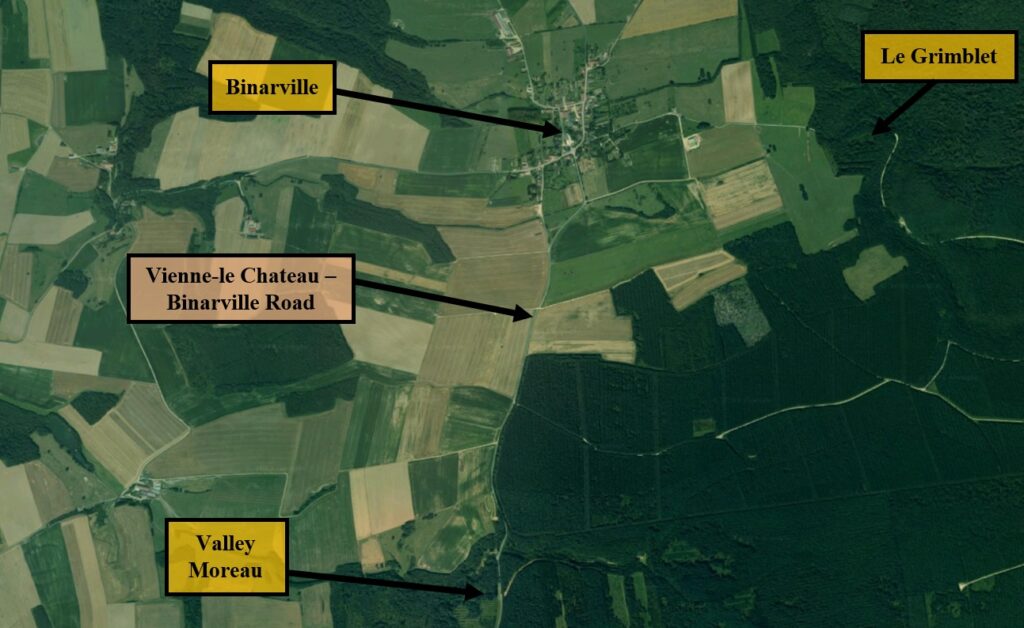

This map represents the target for the 2nd and 3rd Battalion, 368th Infantry Regiment, Groupement Durand, on 27 September 1918. The primary target of the 2 battalions was Tranchee Clotilde, which was positioned to the Northwest of the American lines.

The remainder of the afternoon for the 368th Infantry Regiment, Groupement Durand, was spent advancing across their sector. Compared to the previous day, the attacks were mostly successful, although to various degrees. Company [G] (2nd Battalion) withdrew from its position to prepare for its assault on Tranche de Finlande, with Company [M] sliding over to operate as the right flank of the 2nd Battalion. Company [M] was successful in its attack on Tranche de Finlande. The 368th Infantry Regiment, reached its ordered positions with light casualties by noon of the 27 September 1918. The success on the 27th was in stark contrast to the previous days’ attacks, with the 2nd Battalion (368th Infantry Regiment, Groupement Durand) operating cohesively and unified with good communication. Company [H] and [E] of 2nd Battalion, achieved their objectives ahead of schedule, although Company [E] would eventually retreat from that position to resupply rations and water. At 1230 Hours (12:30 P.M.), the 2nd Battalion was ordered to attack another German line of trenches and fortifications. This assault was unsuccessful and again Major Elser and Company Commanders of the 2nd Battalion lost communication with each other and their troops. The primary cause for the second routing of the entire battalion was cited as a lack of maps, and a densely forested terrain, resulting in platoons losing their sense of direction. Simultaneously, liaison with the left flank of Groupement Durand, the American 77th Infantry Division, was lost entirely, putting the Groupement Durand in a desperate situation. With a growing sense of urgency to avoid the possibility of friendly fire incidents in the wooded area, Groupement Durand HQ deployed company [E] (2nd Battalion, 368th Infantry Regiment, Groupement Durand) to re-establish contact with the 77th Infantry Division, American I Corps, American First Army, which failed in its objective.

Despite widespread confusion in the 2nd Battalion (368th Regiment, Groupement Durand) ranks, the 3rd Battalion, of the same regiment, remained intact and capable. With that, the 3rd Battalion received attack orders for 1730 hours (5:30 P.M.) On the right flank, the French XXXVIII Corps began a column attack across the entire French sector. The column attack, a pretext for Blitzkrieg warfare, involved several concentrated columns of soldiers attacking quickly against a specific target in the enemy’s trenches. Once these quick-moving columns broke through, they would quickly advance to divide and threaten the enemy’s rear. This assault was supported with Artillery from the French 4th Army, and the attack was met with mixed gains, as some units secured their objectives and others were pushed back to where they started.

The 3rd Battalion (368th Infantry Regiment, Groupement Durand) began their attack on schedule that evening. The attack consisted of Company [K] on the right, Company [I] in the middle (Private John Baker’s Company), and Company [M] on the left. At 1900 Hours (7:00 P.M.), the advance of Companies [M], [I], and [K] (3rd Battalion, 368th Infantry Regiment, Groupement Durand) was halted. Companies [I] and [K] remained in the position to the East of the road, with Company [M] on the western side and 200 meters forward. The 3 companies would spend the remainder of the night at these locations without liaison to forces on either side. As it became closer to nightfall, the 2nd Battalion, 368th Infantry Regiment, Groupement Durand, came under heavy fire from both German artillery and German aircraft. Once again this combined to partially scatter the Battalion, with the exception of Company [F], although Company [F] would fall back at 2200 Hours (10:00 P.M.).

In preparation for the next wave of attacks the next day, the Groupement Durand headquarters ordered the Machine Gun Company of 1st Battalion to divide and redeploy to 2nd and 3rd Battalion of the 368th Infantry Regiment. The end result of 27 September 1918 for Groupement Durand, specifically the 368th Infantry Regiment, was widely successful. Although the 2nd Battalion would be partially scattered following the day’s action, it had advanced and held 2 kilometers of German territory. The 3rd Battalion had avoided routing and still advanced 2 kilometers by the end of the day. 2nd Battalion, 368th Infantry Regiment, Groupement Durand, would suffer 27 dead, wounded or gassed by the end of the day, bringing their total losses since the start of the campaign to 58. Additionally, the 2nd and 3rd Battalion would capture 9 German prisoners from the German 3rd Army. In response to attacks across the Argonne Forest, the Germans responded by desperately deploying all reserve units to the front.

-28 September 1918:-

The first order of the day came at 0215 Hours (2:15 A.M.), and ordered the entire Groupement Durand, to attack north coinciding with the French 1st Dismounted Cavalry. The end goal of this unit was to secure Binarville by the end of the day. Placed in command of this combined force was Groupement Durand Headquarters, which was tasked with deciding on the official time of the attack. The unit was given a battery of 75 mm guns, and one 155mm gun. Preparations for the attack were made and involved the 3 Battalions of the 368th Infantry Regiment, Groupement Durand.

1st Battalion, 368th Infantry Regiment, Groupement Durand, was pulled out of its reserve role and deployed to help establish liaison with the other units that formed the Groupement Durand. Its secondary mission was to determine the strengths and depositions within the frontline Battalions, as well as perform combat patrols on the front. The unit would only spend a brief moment on the front before being moved back into reserve duty in the afternoon, this time with the French 1st Dismounted Cavalry Division.

2nd Battalion, 368th Infantry Regiment, Groupement Durand, remained partially disorganized following its second routing since the start of the campaign. Without the companies in proper order, and with communication limited, no coordinated group attack was made for the entire morning to allow time to regroup. The companies under its command were in these positions in the early morning of 28 September 1918;

- Company [E] was reformed and regrouped and places on the right flank of the Battalion in Tranche de Finlande

- Company [F] was the forwardmost unit in the Battalion, North of the town Tranchee Tirpitz, where at 0500 hours (5:00 A.M.), it began to reorganize the platoons and squads that had been thrown into disarray and were stranded following 2nd Battalion’s hasty retreat from its frontline positions on 26 and 27, September 1918

- Company [G] assembled in Tranche de Finlande and was tasked as a support force

- Company [H], during the morning, moved to advance frontline positions, to support the other companies preparing assaults in the later afternoon

3rd Battalion, 368th Infantry Regiment, Groupement Durand, remained relatively unchanged on the day and night of 27 September 1918. The Battalion, although it had seen active combat since the opening of the Argonne Offensive, had suffered only light losses and maintained unit order, makeup, and stability. Thus, it was able to quickly deploy on the battlefield on 28 September 1918, with few problems and good unit cohesion. Following the sunrise at 0645 Hours (6:45 A.M.), the 3rd Battalion deployed on the left of the 2nd Battalion, although it was made more difficult due to heavy overcast and rain, which led to low visibility. Nevertheless, at 0730 Hours (7:30 A.M.), 3rd Battalion, 368th Infantry Regiment, Groupement Durand, deployed in the following order

- Company [I] operated as the middle/center company (Private John Baker’s company)

- Company [K] was the rightmost company

- Company [M] was the leftmost company

- Company [L] was placed in reserve.

The 3rd Battalion, 368th Infantry Regiment, Groupement Durand, made steady progress in the attacks that morning. The unit advanced 2 kilometers to the targeted German position. For the three front line companies, [I], [K], and [M], the advance was easy, with little to no German resistance to the movement. At this point in time, a critical error was made by the 2nd Battalion, 368th Infantry Regiment, Groupement Durand. The 3rd Battalions’ rapid advance had not been followed by the 2nd Battalion, who was operating as the right flank. This meant that the 3rd Battalion, 368th Infantry Regiment, Groupement Durand, was entirely exposed along the entire right side of its line, and should even a small German unit realize the mistake, German soldiers could have swept behind the 3rd Battalion and use its position and surprise to destroy the American unit from the rear. Such a maneuver could potentially be catastrophic, as the collapse of the 3rd Battalion, especially with the fragility of the 2nd Battalion, could result in an entire frontline sector being left undefended.

It was at this point where Private John Baker’s actions came into prominence. With the 3rd Battalion realizing the critical error, headquarters requested a runner to deliver the urgent message to the 2nd Battalion. Private John Baker, although he had been engaged in constant combat since the start of the offensive, volunteered without prompting to assist. At 1125 hours (11:25 A.M.), he and one other runner left the relative safety of 3rd Battalion trenches and ran to deliver the message 2 kilometers behind 3rd Battalion lines. To do this he had to run across vast and open terrain, with no cover and with the risk of encountering German patrols in the area. Shortly after departing the 3rd Battalion, the two men encountered a German force of unknown strength, wielding machine guns and mortars. Following the two men coming under fire, the other runner assigned to help Baker promptly deserted him and ran back to the 3rd Battalion’s line. Despite being deserted, carrying just a sidearm for protection, and facing heavy machine-gun fire, Private Baker continued to run across the open area to deliver his message. By this point, Private Baker’s position had been reported back to German artillery, and he came under heavy bombardment. Shortly after, one of the artillery shells landed near him, mutilating his hand, and destroying 2 fingers. Still he continued with the message and delivered it by 1200 hours (12:00 P.M.)

In his Distinguished Service Cross citation, Private Bakers actions were described by the Army report as “Although severely wounded in the right hand, losing 2 fingers, Private Baker, a runner continued 300 yards through heavy machine-gun fire… he delivered his message alone, having been deserted by an unwounded fellow runner.” Following the bravery and heroic actions taken by Private John Baker, he said in response to a question of why he didn’t attempt to seek aid for his wounds, “I thought the message might contain information that would save lives.”

Following the engagements of that morning and early afternoon, official military questioning into why the 2nd Battalion did not advance in conjunction with the 3rd Battalion (Both of the 368th Infantry regiment, Groupement Durand), found that Major Elser (Commanding Officer, 2nd Battalion), did not recall ever receiving communication that the 3rd Battalion was advancing or that its right flank needed covering. This statement was countered by a member of Groupement Durand headquarters, who stated the orders were “delivered personally,” on the morning of 27 September 1918.

Regardless of who was at fault for the incident, the orders delivered by John Baker may have helped to preserve the lives of the men of the 3rd Battalion, 368th Infantry Regiment, Groupement Durand. By later that day, the 3rd Battalion, this time in conjunction with the 2nd Battalion, began another advance forward. This ended in complete disaster with the 3rd Battalion being routed and forced into retreat, with separate companies deciding to retreat un-cohesively and under their own initiative. This was partially due to the lack of support from the 2nd Battalion, and also due to inaccurate artillery assistance. This would be one of the 2nd Battalions’ final actions before withdrawing into a reserve role for months to follow. The 2nd Battalion’s dismal performance in the 4 days of combat was detrimental to the actions of the 3rd Battalion, and the person at fault for the incident that put Private Baker in that position was never fully uncovered.

In 1921, Baker underwent rehabilitation training via the *Federal Board of Vocational Education, commencing his training at the Cheyney Institute, Cheyney, Pennsylvania, as an auto mechanic in April, ending in August. Baker was placed in a Philadelphia mechanic shop in August of 1921 and remained until February of 1923, he moved to Paige Service Station in February of 1923, remaining until January of 1924. In September of 1924, he worked at Cato’s Garage in Philadelphia. A brief incident occurred in March of 1924, when Baker, as reported by his training officer E.B. Pollard, “was absolved by last Counsellor but took a car from Garage without owner’s permission & had a smashup. I tried to get Mr. Cato to reconsider”. It is unknown how long Baker remained at Cato’s Garage- in 1930, he was a laborer for a phonograph company.

Baker was involved with multiple women; in the late 1910s, Julia Ann Smith (Byrd, Washington, 1890-1952) was listed as his wife on his 1918 U.S. Army Transport List, however, the couple were only common-law. The partnership was dissolved before 1922. On 22 February 1922, Baker married Annie May Allen (Grant, Reed, Robinson, Bailey, Jones, 1880-?), who had two children from previous relationships, Spalding Grant (1898-?) and Ralph Jones (1917-1995). Baker adopted (unknown if formally) Ralph Jones, who used the name Ralph Baker into his adulthood. Baker and Allen separated in the 1930s, and he began a relationship with Virginia Hayes (?-?), which lasted until his death in 1938, “she and the veteran lived together as husband and wife but she never assumed the name of veteran…in view of the complications of the claimant’s marital status, and the fact that the previous marriage had not been dissolved by divorce, it does not appear that she would have a just claim as a widow”.

Baker began suffering from a variety of health issues into the late 1930s, and was diagnosed with cirrhosis of liver and syphilis in April of 1938. He was admitted to the U.S. Naval Hospital in Philadelphia for the final time on 21 December and died on 24 December, the result of Central Nervous System Syphilis and Chronic Cholecystitis. It is unknown were Baker is buried.

*The Federal Board for Vocational Education (1917-1946) was a division of Vocational Rehabilitation for Disabled Soldiers, Sailors, and Marines, active post-War. “Men, who are disabled for certain trades or occupations, may learn more suitable ones in which the disability will not be such a serious handicap. The Federal Board has been given the responsibility of arranging the necessary training” (Federal Board for Vocational Education memo, April 18, 1921, Item JB 2.6. Copy from Military Personnel Files from the National Archives and Records Administration Military Personnel Records Center held at the George S. Robb Centre for the Study of the Great War, Parkville, MO.).

Excerpt from W. Allison Sweeney's History of the American Negro in the Great World War

“Another single detail taken from the same Company I:

John Baker, having volunteered, was taking a message through heavy shell fire to another part of the line. A shell struck his hand, tearing away part of it, but the Negro unfalteringly went through with the message.

He was asked why he did not seek aid for his wounds before completing the journey. His reply was: I thought that the message might contain information that would save lives.

Has anything more heroic and unselfish than that ever been recorded? Nature may have, in the opinions of some, been unkind to that man when she gave him a dark skin, but he bore within it a soul, than which there are none whiter; reflecting the spirit of his Creator, that should prove a beacon light to all men on earth, and which will shine forever as a ‘gem of purest ray serene’ in the Unmeasurable and great Beyond.”