Edward Louis Merrifield

Military Honor(s):

Distinguished Service Cross

Citation: The President of the United States of America, authorized by Act of Congress, July 9, 1918, takes pleasure in presenting the Distinguished Service Cross to Private Edward L. Merrifield (ASN: 2817823), United States Army, for extraordinary heroism in action while serving with Company E, 366th Infantry Regiment, 92d Division, A.E.F., near Lesseux, France, 4 September 1918. Although he was severely wounded, Private Merrifield remained at his post and continued to fight a superior enemy force which had attempted to enter our lines, thereby preventing the success of an enemy raid in force.

Purple Heart

Life & Service

- Birth: 28 December 1888, Greenville, IL, United States

- Place of Residence:

- Race/Ethnicity: African American

- Death: 20 January 1952 , IL, United States

- Branch: Army

- Military Rank: Private

- Company: [E]

- Infantry Regiment: 366th

- Division: 92nd

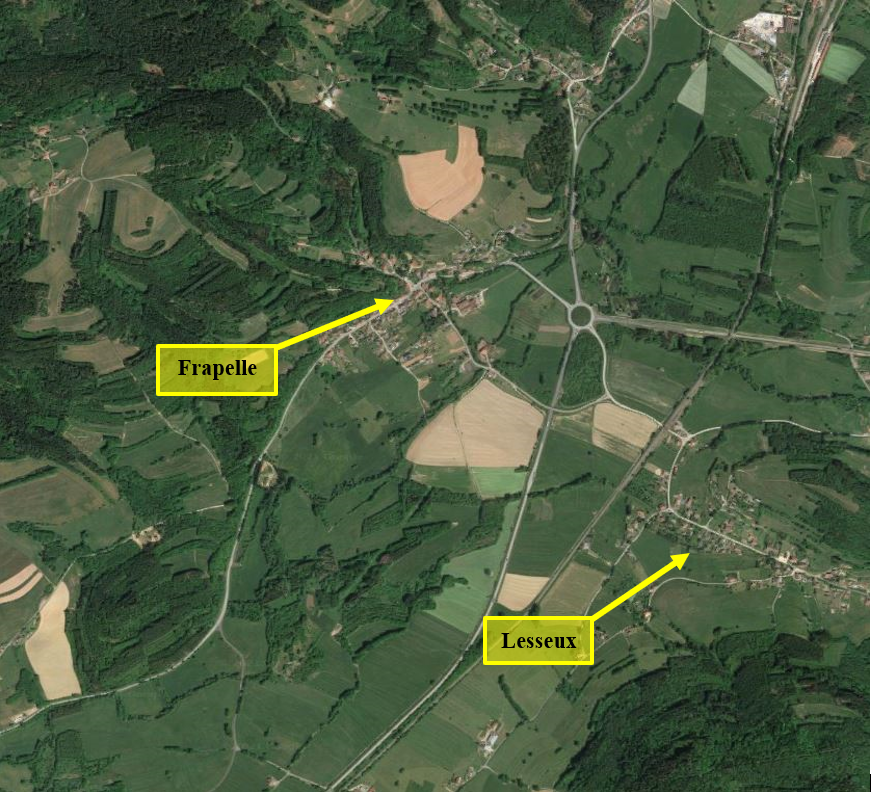

Private Edward Merrifield served in Company [E], 366th Infantry Regiment, 92nd Division. At the time of his act of valor on 4 September, 1918, his unit was stationed at Lesseux in the Saint-Dié Sector. What follows is his story.

Saint-Dié Sector – 3 September 1918

August 1918:

Situated directly on the Franco-German border in 1914, what would become the Saint-Dié Sector saw some of the First World War’s earliest battles. However, by 1918 this same sector had developed a reputation as one of the few quiet regions on the Western Front, with the frontlines growing static as early as the Fall of 1914 — a fact due largely to the naturally defensible terrain of the Vosges Mountains. Since then, it had been designated as a rest sector by both sides of the conflict, meaning that it was a common destination for exhausted or inexperienced units that were unfit for more fearsome sectors. This made the Saint-Dié Sector an ideal training ground for the inexperienced soldiers of the American Expeditionary Forces that began trickling into France in 1917.

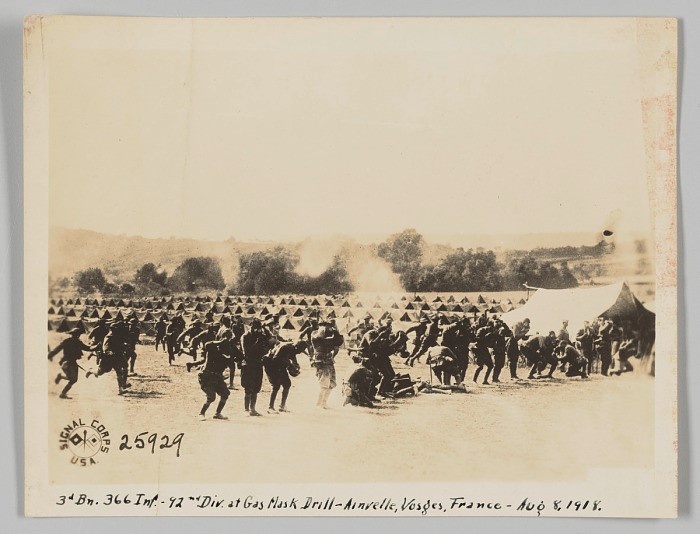

3rd Battalion, 366th Infantry Regiment performing gasmask drills at Ainville, Vosges France – 8 August, 1918.

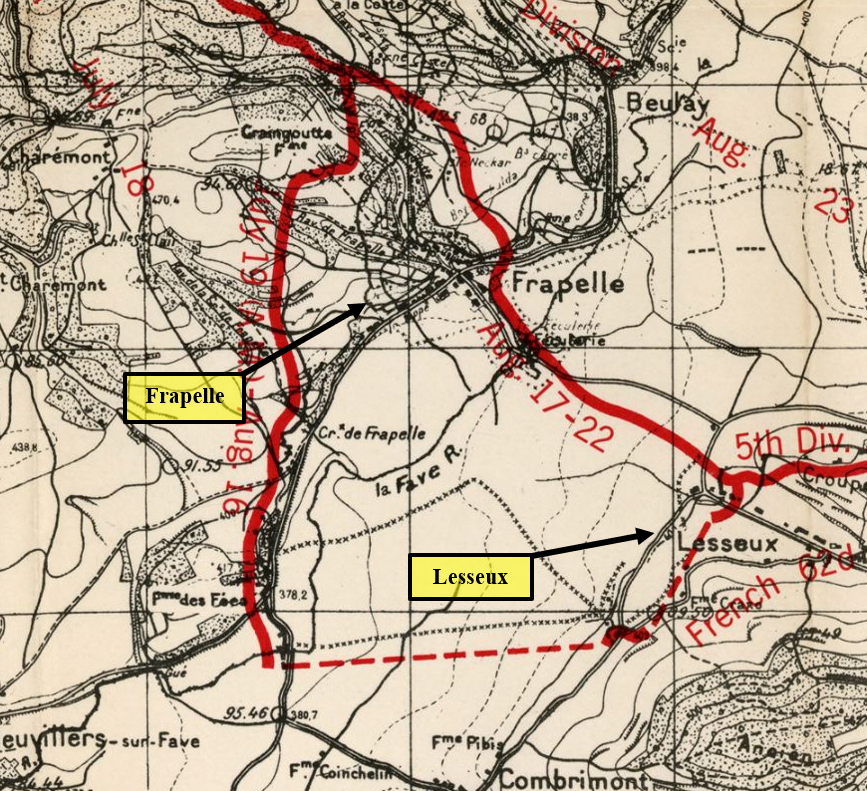

One such unit was the American 5th Infantry Division, which disturbed the uneasy peace of the Saint-Dié Sector on 16 August, 1918. Brigaded with members of the French XXXIII Corps, the 6th Infantry Regiment, 5th Division, launched a surprise attack on the strategically significant town of Frapelle. Following its capture on 17 August, Frapelle became the focal point of German forces in the Vosges Front, who began to plan an extensive operation to retake the town. However, the 5th Division would not have to withstand the German assault for long, as from 21-23 August the 92nd Infantry Division, under the guidance of the French 87th Division, assumed control of the sector. The African-American soldiers received a bloody welcome to the Western Front when, on 23 August, two members of the 366th Infantry Regiment were killed and several others were wounded during a German artillery barrage. These were the 92nd Division’s first casualties as the result of enemy fire.

1 – 3 September 1918:

The 92nd Division got their first taste of German flamethrowers, such as this one, in the Saint Die Sector.

Through the final week of August, 1918, German raiders skirmished with the 92nd Division’s patrols throughout no-man’s-land and their artillery filled the sector with high-explosive and chemical munitions. However, though these early struggles took their toll, the intensity of the German offensive increased on the night of 31 August and the early morning of 1 September when the Germans launched a massive assault on the 92nd Division’s lines. Mustard gas choked the air and streaks of fire – the lethal discharge of German flamethrowers – flashed through the cool mountain night as German raiders attempted to drive the Allied soldiers from their trenches. However, artillery fire from the French XXXIII Corps (the 92nd Division’s own 167th Field Artillery Brigade was undergoing training behind friendly lines until Mid-October, 1918) was able to drive the Germans away. When the sun finally rose over the mountains, German bodies littered the pass, but this victory came at a cost. The 92nd Division counted 4 dead and 34 gassed or wounded, including First Lieutenant Thomas Bullock of the 367th Infantry Regiment. He was the first officer of the 92nd Division to be killed in action.

In the afternoon of 1 September, the Germans attacked again and an intense firefight broke out on the slopes of Ormont, west of Frapelle, between members of the 92nd Division and the German raiders. However, the combined efforts of the 365th and 366th Infantry Regiments were able to force the Germans back once more. That night, patrols from the 92nd Division found that the Germans had left their foremost trenches unoccupied, which was taken as a sign that the Germans were preparing for a general engagement. The 92nd Division did not oblige the Germans by mounting a counterattack. Instead, the men of the 92nd Division spent the second day of September, 1918, performing maintenance on their battered frontline, despite constant pressure from the German guns. Frustrated at their enemy’s inaction, the Germans launched another attack on the 366th Regiment’s front on 3 September, in which Second Lieutenant Aaron Fisher was badly wounded. Yet he held his ground, setting an exemplary model for the rest of his men to follow. The Germans, meanwhile, were beginning to lose faith.

An example of the small-box-respirator type masks used by the 92nd Division.

As a result of the large amounts of gas used in these attacks, the 92nd Division’s gas officers were able to identify numerous problems with their men’s protective equipment and gas discipline. Though daily gas drills were able to remedy the latter, the former proved a much greater challenge to overcome. This was because the Small-Box Respirator (SBR) type gas masks issued to the 92nd Division did not properly fit many of the men. As a result, over 1,500 members of the 92nd Infantry Division had to make-do with inadequate or dysfunctional gas protection. Further compounding the issue, in at least one incident on 2 September, 1918, smog from high-explosive ordnance grew so thick that one officer and several men were unable to identify the smell of mustard gas in their dugout, and were subsequently gassed.

4 September 1918:

A German gas attack on soldiers during World War One. Dated 1914. (Universal History Archive/UIG via Getty Images) – Colourized.

On 4 September, a large German raid struck the 366th Infantry Regiment near the small town of Lesseux, just to the East of Frapelle. The initial bombardment by artillery and minenwerfers had collapsed sections of the 366th Infantry Regiment’s trenches, wounding, burying, or killing many men. Those who could still fight had only barely recovered by the time that a large group of German raiders appeared and began to assault their frontline. Armed with terrifying wechselapparat flamethrowers, the Germans shot jets of liquid fire into the American lines in a terrifying show of force. However, a handful of surviving members of the 366th Infantry Regiment held their positions and mounted an organized resistance to the German attack. One such person was Private Edward Merrifield, who held his position and fought back until the Germans were compelled to retreat despite being badly wounded during the enemy attack. It was because of men like Private Merrifield that the Germans were never able to penetrate the 366th Regiment’s lines during their stay in the Saint-Dié Sector. Consequently, the Germans soon came to respect the soldiers of the 366th Infantry Regiment who so vigorously resisted them. Their lines, the Germans believed, were unassailable.

For his part in repelling the German raid on Lesseux, Private Edward Merrifield was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross in 1919 under General Orders No. 15. He also received the Purple Heart in recognition of wounds sustained during his time in the Saint-Dié Sector.

Several other members of the 92nd Infantry Division were awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for actions near Lesseux on September 4, 1918. Their names and links to their own Personal Narratives are included below.

Sergeant (Then-Private) Roy A. Brown, [E] Company, 366th Infantry Regiment.

Corporal Van Horton, [E] Company, 366th Infantry Regiment.

Private First-Class William Clincey, [F] Company, 366th Infantry Regiment.

Private George W. Bell, [E] Company, 366th Infantry Regiment.