William Clincey

William Clincey’s Personal Narrative was derived from information found in public records, military personnel files, and local/state historical association materials. Please note that the Robb Centre never fully closes the book on our servicemembers; as new information becomes available, narratives will be updated to appropriately represent the life story of each veteran.

Please contact the Robb Centre for further clarification or questions regarding content or materials.

Military Honor(s):

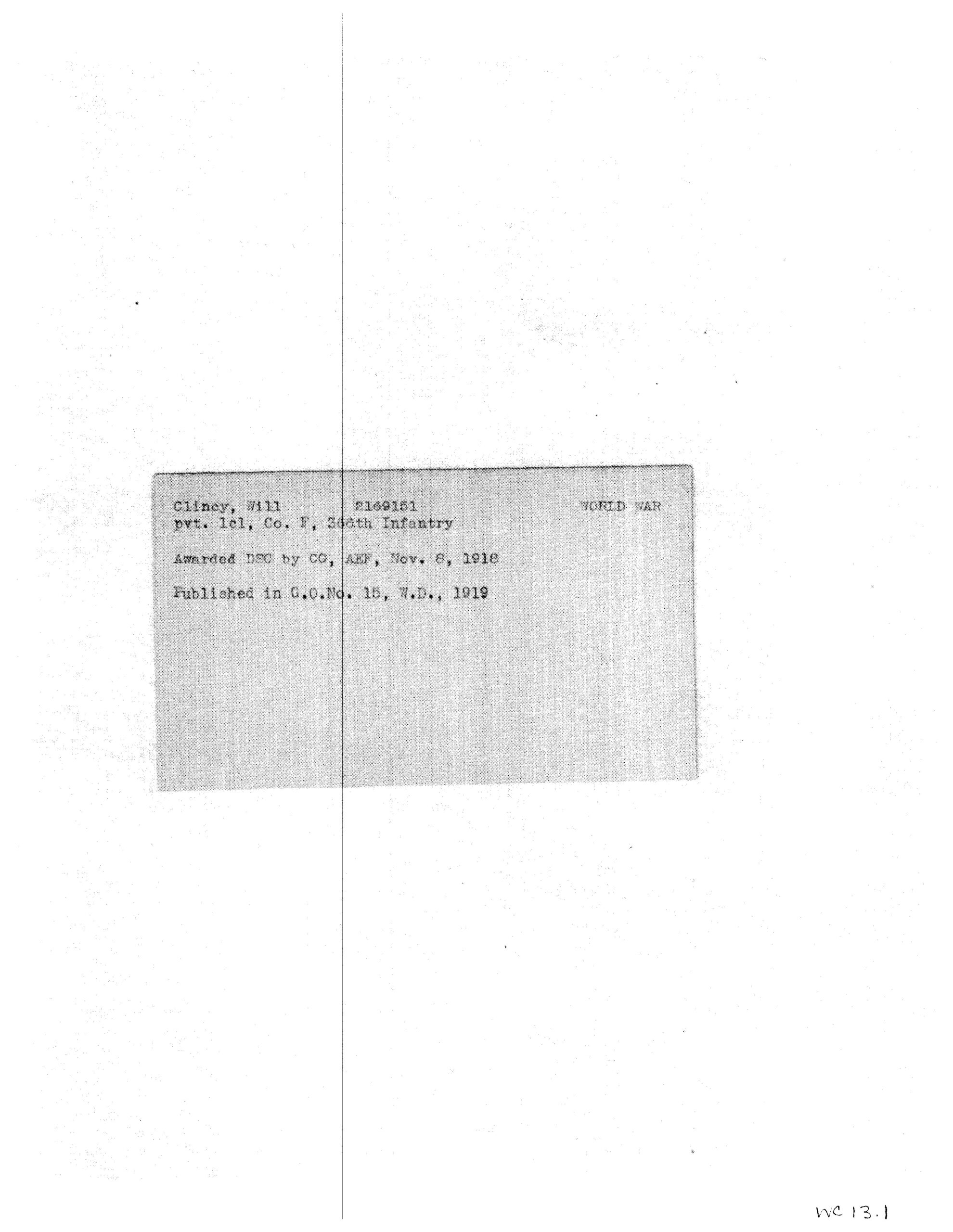

Distinguished Service Cross

Citation: The President of the United States of America, authorized by Act of Congress, July 9, 1918, takes pleasure in presenting the Distinguished Service Cross to Private First Class Will Clincy, United States Army, for extraordinary heroism in action while serving with Company F, 366th Infantry Regiment, 92d Division, A.E.F., near Frapelle, France, 4 September 1918. He showed exceptional bravery during an enemy raid. His teammate on an automatic rifle having been mortally wounded, and although he was himself severely wounded he continued to serve his weapon alone until the raid was driven back.

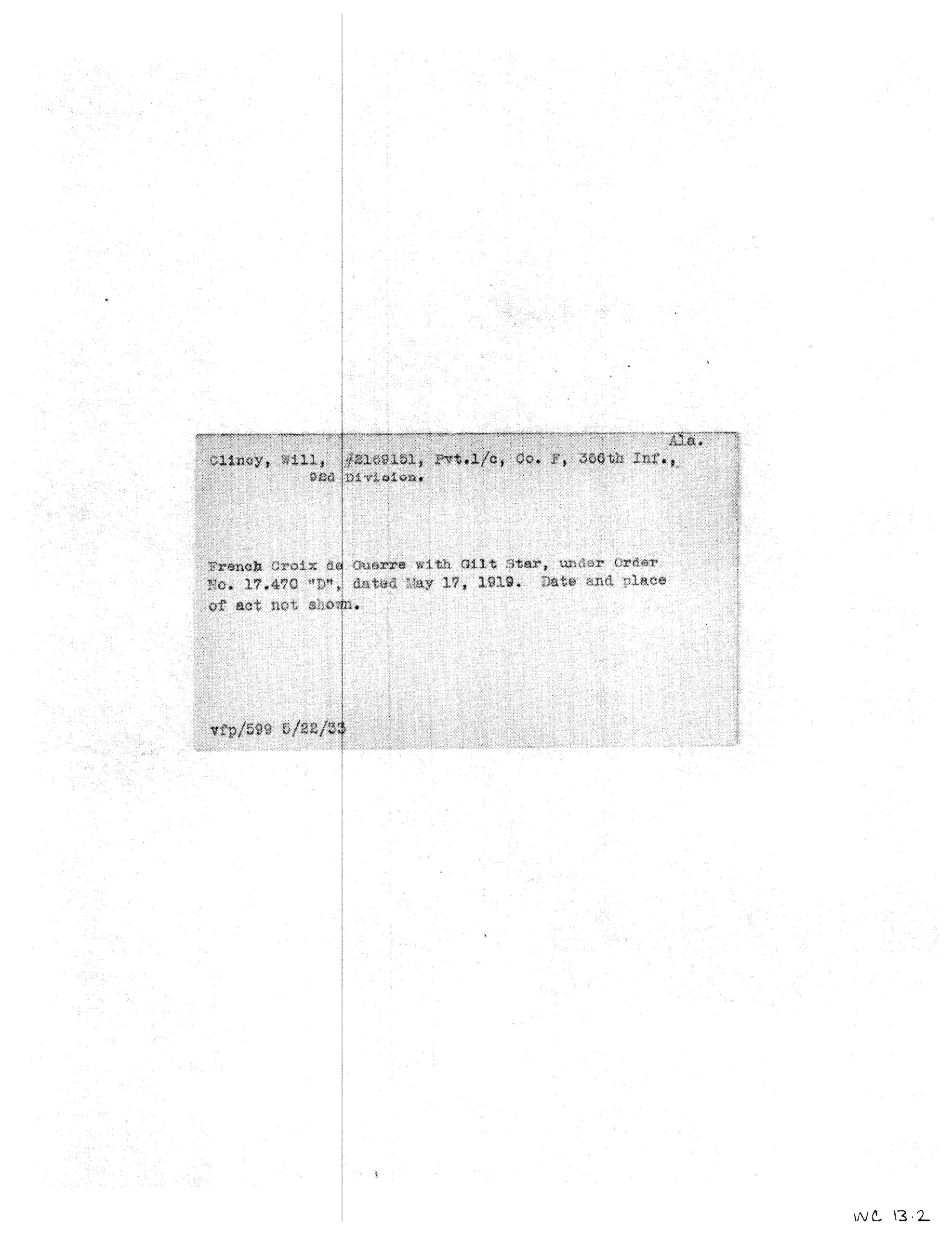

Croix de Guerre with Silver Gilt Star

Life & Service

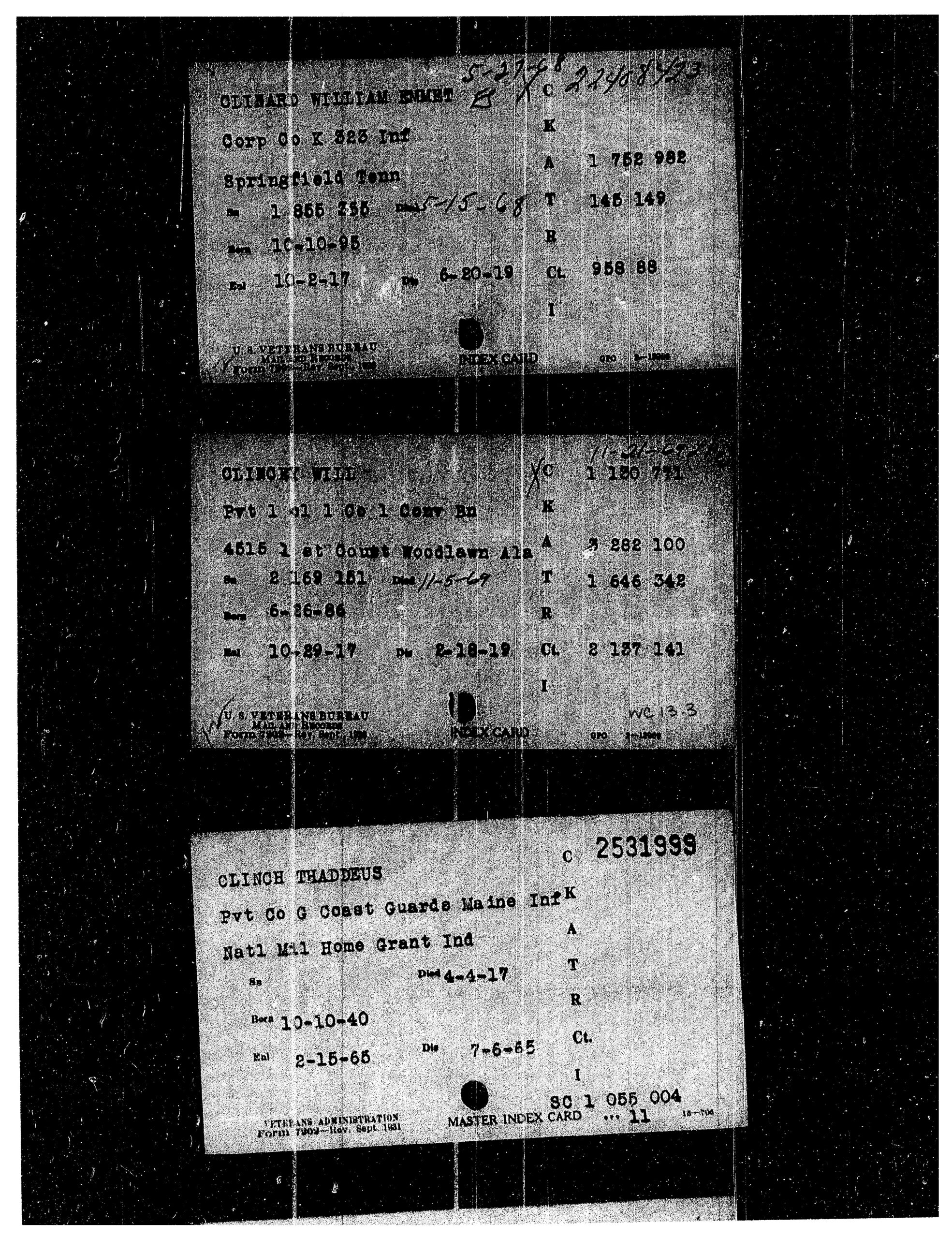

- Birth: 25 June 1886, Marion, AL, United States

- Place of Residence:

- Race/Ethnicity: African American

- Death: 5 November 1969 Birmingham, AL, United States

- Branch: Army

- Military Rank: Private First Class

- Company: [F]

- Infantry Regiment: 366th

- Division: 92nd

William Clincey was born to John (1868-?) and Martha Robinson (1874-?) on 26 June 1886 in Marion, Alabama, the eldest of five children, Ed (1889-?), Lella (1891-?). Charlie (1893-1980) and John Jr. (1896-1953). William worked as a farmer in Perry County, Alabama before enlistment; he was married to Mae L. (Maiden name unknown) (1890-?) in the 1910s.

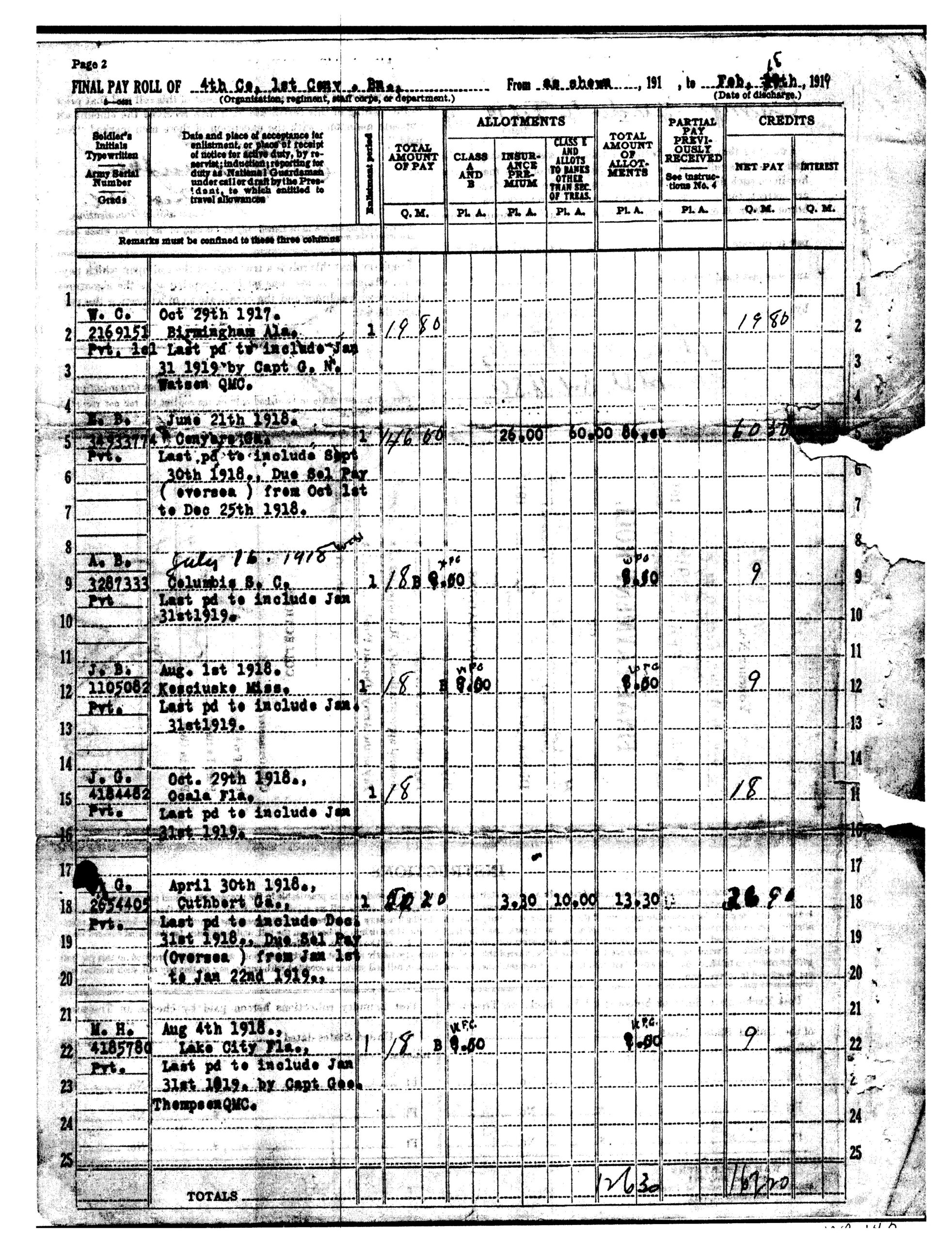

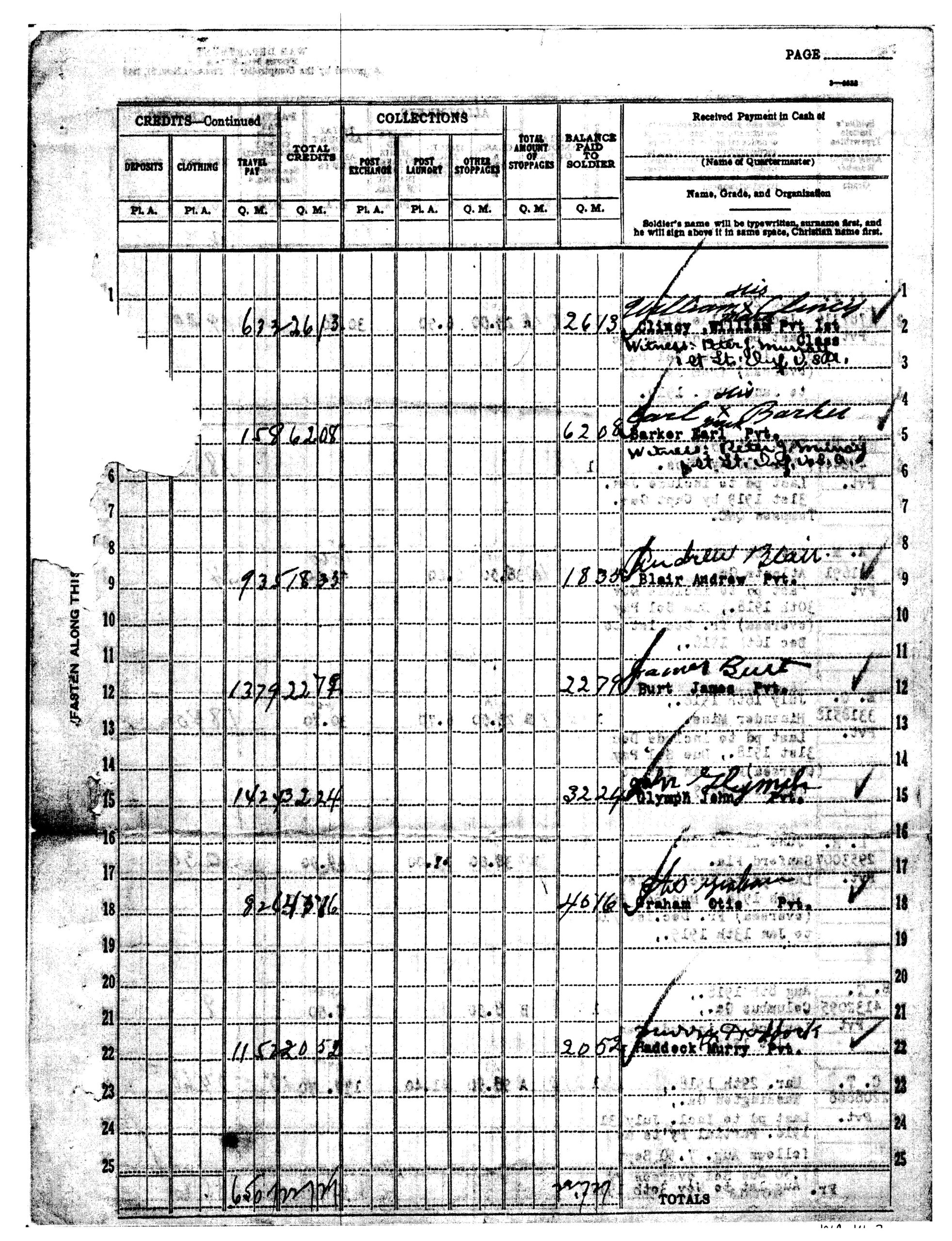

Will Clincey enlisted in the U.S. Army on 29 October 1917. Private Clincey and his company left Hoboken, New Jersey on the U.S. Army Transport Ship Vauban on 14 June 1918, arriving in Brest, France on 21 June. Clincey received the Distinguished Service Cross and French Croix de Guerre w/Gilt Star for his actions near Frapelle, France on 4 September 1918;

“The President of the United States of America, authorized by Act of Congress, July 9, 1918, takes pleasure in presenting the Distinguished Service Cross to Private First Class Will Clincy, United States Army, for extraordinary heroism in action while serving with Company F, 366th Infantry Regiment, 92d Division, A.E.F., near Frapelle, France, 4 September 1918. He showed exceptional bravery during an enemy raid. His teammate on an automatic rifle having been mortally wounded, and although he was himself severely wounded, he continued to serve his weapon alone until the raid was driven back”. Awarded DSC by CG, AEF, November 8, 1918. Published in G.O. No. 15, W.D., 1919. French Croix de Guerre with Gilt Star, under Order No. 17, 470 “D”, dated May 17, 1919. Date and place of act not shown.

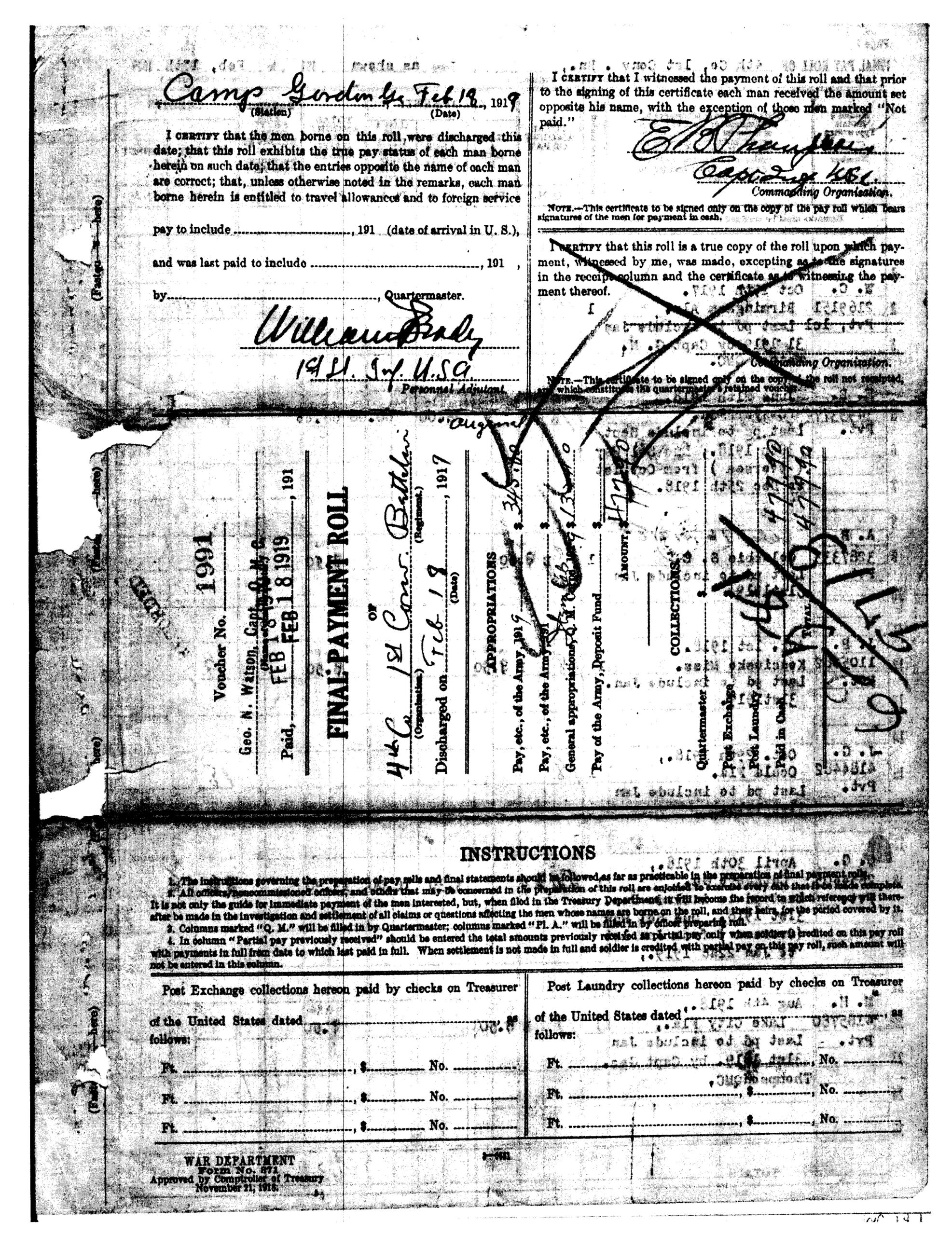

Then-Private FC Clincey left Breast, France on the U.S. Army Transport Ship Aeolus on17 December 1918, arriving in Newport News, Virginia, on 30 December 1918. Private FC Clincey was Honorably Discharged on 18 February 1919.

Private First Class William Clincey served with Company [F], 366th Infantry Regiment, 183rd Infantry Brigade, 92nd Division. During combat in the vicinity of Lesseux, France, Clincey’s actions earned him the Distinguished Service Cross and the French Creux de Guerre with Silver Gilt Star. This is his story.

The Saint-Dié Sector – 4 September 1918:

August 1918:

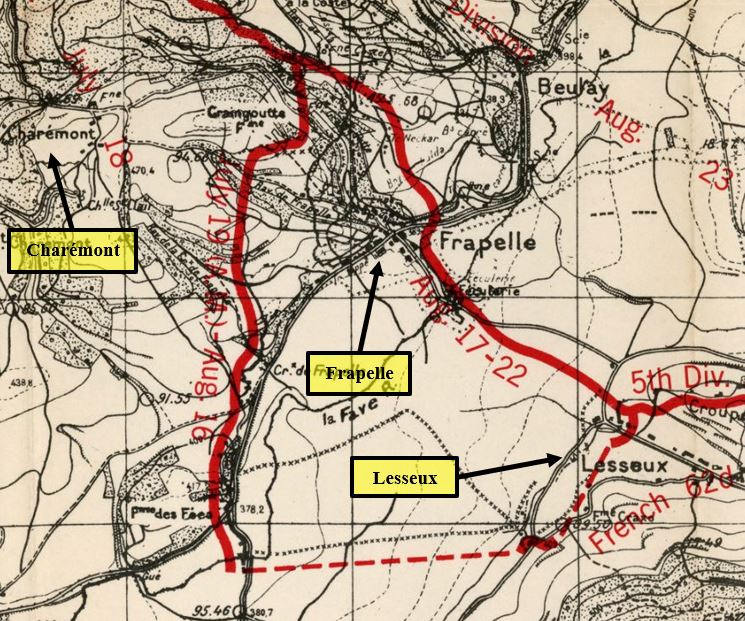

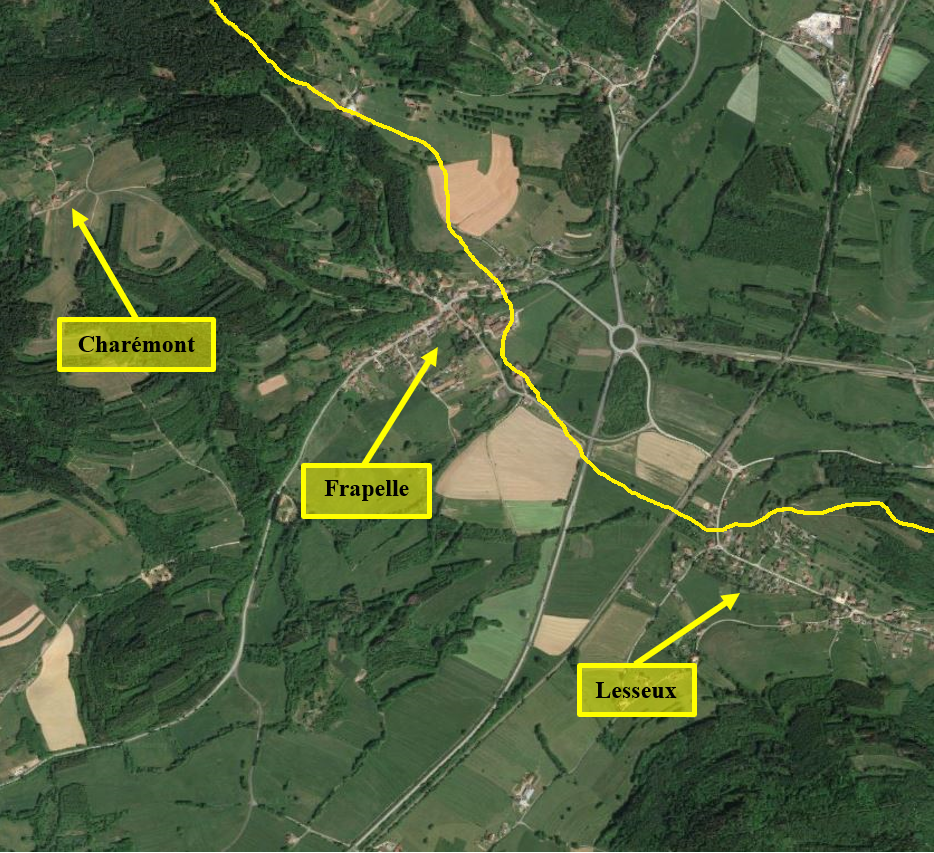

Located deep within the Vosges Mountains of France, the rough terrain inherent to the Saint-Dié Sector made maneuvering difficult and, as early as 1914, action along this front had stagnated. This changed when the American 5th Infantry Division assumed control of the sector on 19 July, 1918, and immediately set their sights on the village of Frapelle. Captured by the Germans shortly after the war began, this small town formed a wedge so deep into the Allied frontline that it inhibited communications between their forces guarding Lesseux and Charémont. Additionally, this salient sat directly on top of the only highway leading through the Saales Pass, which was one of the few viable passages through the Vosges Mountains. Consequently, German control of this town not only weakened the entire Allied frontline through the sector, but gave the Germans a direct rout straight into the French city of Saint-Dié-des-Vosges, for which the Saint-Dié Sector was named. Due to this overwhelming strategic importance, the Americans decided that the German occupation of Frapelle was intolerable and, following a surprise attack on 17 August, 1918, the village came back under Allied control.

A view of the Saint Die Sector from one of the many heights. Frapelle, France can be seen in the center.

When the 92nd Infantry Division relieved the 5th Division on 22 August, they found that the once quiet sector had become inflamed. Furious that the Americans had broken the peace, the Germans were launching frequent raids, gas attacks, and aerial bombardment. The men of the 366th Infantry Regiment were the first to receive this veritable baptism by fire and, as they assumed control of the center of action around Frapelle they were swept up in a violent enemy bombardment. As a result, 2 men were killed and another 6 were wounded. The 92nd’s experience in the Saint-Die Sector, originally intended to be an easy deployment in which they would learn the ins-and-outs of trench warfare, instead served as a comprehensive guide to the horror of the War to End All Wars.

1-3 September 1918:

The severity of the German offensive increased on the night of 31 August and morning of 1 September, when the Germans attempted to seize Frapelle via an extensive attack all-along the 92nd Division’s front. Muzzle flashes, explosions, and streaks of liquid-fire lit up the night as a massive battle raged through the Saales Pass. However, the 92nd Division’s lines held and, following a devastating barrage from the French Artillery that had been assigned to support the 92nd Division (the 92nd Division’s own 167th Field Artillery Brigade was still in training at this time), the Germans were driven back to their own lines. The attack resumed that afternoon and, from 1230 Hours (12:30 PM) to 1500 Hours (3:00 PM) the German pelted the 92nd Division’s frontline with artillery. Before the smoke had cleared, a terrifying cry resounded through the valley and the German infantry scrambled up the slopes of Ormont. Yet, despite the bombardment, the men of the 365th and 366th Infantry Regiments stood ready, and the charging enemy fell before their guns.

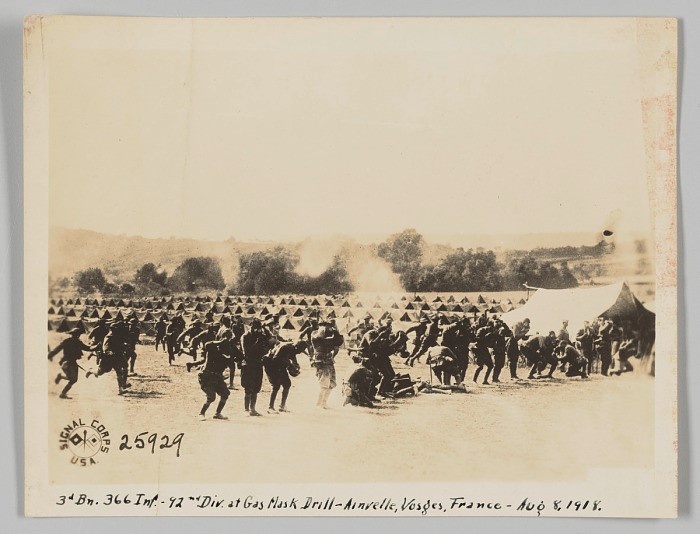

3rd Battalion, 366th Infantry Regiment, 92nd Division at Gas Mask Drill in Ainville, Vosges, France, August 8, 1918.

The Germans spent the second day of September, 1918, licking their wounds under the cover of an extensive artillery barrage. High explosive and gas shells fell onto the 92nd Division’s lines throughout the day and German Machineguns raked the open ground between their trenches, forcing the American infantrymen to hunker-down in their dugouts until the storm had passed. However, as a result of the extensive gas attacks, many men had to be evacuated due to prolonged exposure to sulphur mustard or diphenylchlorarsine (“mask-breaker”) gas. In one particular incident, an officer and several enlisted men were badly poisoned after failing to identify the distinctive scent of mustard gas in their dugout. When questioned how they had failed to smell the toxic gas, they claimed that the smoke from the high-explosive ordnance had grown too thick and smothered the scent. According to the 92nd Division gas officer, many of these casualties could have been prevented had it not been for the fact that the Small Box Respirator (SBR) types gasmasks that had been issued to the 92nd Division did not properly fit many of the men, a flaw that the 92nd Division had to contend with until the end of the war.

The following day, on 3 September, the German infantry went back on the offensive. Shifting their focus to the East, the Germans launched a large raid on the 366th Infantry Regiment’s lines around the town of Lesseux. In the ensuing firefight, Second Lieutenant Aaron Fisher became the first member of the 92nd Division to distinguish himself in combat when he, despite being badly wounded by enemy fire, remained in the field to command his troops until the Germans were driven from the field. Unfortunately, though the Germans were repelled, this was not their last attempt to take Lesseux by a raid in force.

4 September 1918:

On 4 September, the shrieks of minenwerfers filled the air. An extensive bombardment from the German trench mortars once more struck the 366th Regiment at Lesseux, throwing great mounds of earth into the sky and even collapsing sections of their trench, burying several members of the regiment alive. As the men who were still standing scrambled to aid their fallen brothers, fire burst forth from no-man’s-land and a large German raiding party descended onto the bruised, battered, and often bleeding members of the 366th Infantry. A small group of soldiers from [E] Company scrambled to meet the attacking Germans despite the overwhelming odds, but the situation was dire.

From the other side of the Saales pass, a handful of members of [F] Company, 366th Infantry Regiment, attempted to aid their companions who were bearing the brunt of the enemy assault. This included an as-of-yet unidentified automatic rifleman who, armed with a powerful fully-automatic weapon, begin laying down a lethal field of fire on the German Infantry. However, the Germans quickly responded and the automatic rifleman’s gun went silent. Realizing what had just happened, an already wounded Private First-Class William Clincey attempted to aid the wounded man, but his condition was dire. Thus, Private Clincy instead took up the dying man’s gun and returned fire. A torrent of bullets flew from the automatic rifle, forcing the German infantry to duck back into cover or be torn apart in a flurry of automatic firepower. With the enemy’s movement now restricted by Clincy’s fire, the men of [E] Company were able to rally and drive the enemy from the field, preventing an incursion into the 92nd Division’s lines. In the aftermath of the battle, Private First-Class Clincey was evacuated for immediate medical attention.

For this heroic act, Private William Clincey was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross under General Orders No. 15 and the Croix de Guerre with Silver Gilt Star under Order No. 17.470 “D.” As a result of his hospitalization, Clincey received these medals while he was no longer with his Division.

Several other members of the 92nd Infantry Division were awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for actions near Lesseux on September 4, 1918. Their names and links to their own Personal Narratives are included below.

Sergeant (Then-Private) Roy A. Brown, [E] Company, 366th Infantry Regiment.

Corporal Van Horton, [E] Company, 366th Infantry Regiment.

Private George W. Bell, [E] Company, 366th Infantry Regiment.

Private Alex Hammond, [E] Company, 366th Infantry Regiment.

Private Edward L. Merrifield, [E] Company, 366th Infantry Regiment.

Clincey worked as a plumber with the Alabama Supply Company in Birmingham, Alabama, and later as a pipe layer for W.D. Pulliam Wood Co., Alabama.

He married Katie Lee Wooten (1895-?) on 27 February 1921 in Jefferson County, Alabama. They had one child together, Lois (1938-?); Will adopted Katie’s four children, Bennett (1910-1983), Willie (1914-1947), Ira (1915-?), and Luella (1920-1953). Sometime between 1940-1970, Will married Lillie George (1901-1974) in Alabama.

William died of a heart attack on 5 November 1969 at his home in Birmingham, Alabama (1821 Fresno Avenue SW).